Madaris of Kolkata – the gypsy street magicians

Magic is an art form. As a performance-art, magic shares the same theatrical qualities and needs, in common with plays, operas, musicals, ballets, and other performance-based art-forms. Magicians are, therefore, artists. But how far can this art penetrate within the fabric of the mainstream society and impact people? Is it possible for magic to inspire people or help the masses transcend their limitations, break the invisible shackles and get over impediments? Sounds incredible? But hold your judgment for a while until you read this story. It did happen once in the past in Kolkata itself.

Madaris, despite their fantastic claims, were very successful in their art of mesmerizing the masses with their acts. Their magical acts were wondrous, enchanting and miraculous. Unlike contemporary shows which are polished professional-quality theatrics where the magician encounters his audience with a pre-conceived scripting, staging, flow, emotionality, acting and direction, as well as production values and artistic design, the Madaris performed under the sky with just a handful of objects, with none of the advantages that the modern magician avails, and yet, excelled in their art.

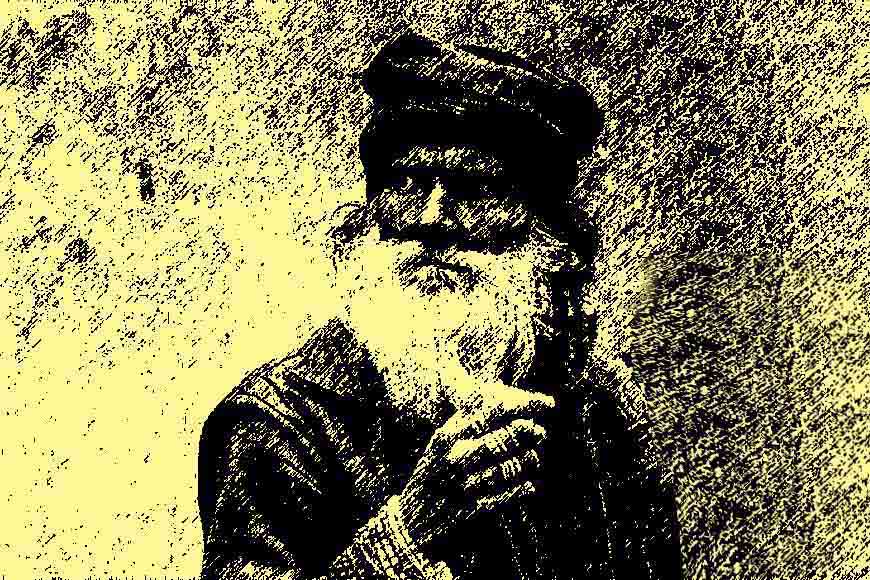

This was the Kolkata of the last century and forms of entertainment were limited. In the 1960s and 1970s, street performers, commonly referred to as Madari aka Jadoogar roamed the streets of the city, demonstrating myriad tricks and magical acts in the open at street corners. These roving magicians in their strange gypsy attires evoked both suspicion and reverence. Adults and children from all walks of life would be captivated by their abracadabra acts and gravitated towards these magicians when they spotted one on the road.

The Madaris usually carried multi-coloured quilt bags that contained knick-knack items like balls of different sizes, a few bowls, feathers, a ‘magic’ wand and human ‘bones’. They would claim the bones were procured from powerful Tantriks and Aghori sanyasis who were masters of the dark forces and performed their mysterious acts in the burning ghats at the dead of night. The Madaris would claim the bones had supernatural power and could even resurrect the dead.

Also read : Kolkata was once called 'Black Town'

However, there is no denying the fact that the Madaris, despite their fantastic claims, were very successful in their art of mesmerizing the masses with their acts. Their magical acts were wondrous, enchanting and miraculous. Unlike contemporary shows which are polished professional-quality theatrics where the magician encounters his audience with a pre-conceived scripting, staging, flow, emotionality, acting and direction, as well as production values and artistic design, the Madaris performed under the sky with just a handful of objects, with none of the advantages that the modern magician avails, and yet, excelled in their art. In fact, these Madaris were the precursor of modern magicians in the subcontinent. One such brilliant Madari was Rahamatullah of Kolkata, whose name is familiar amid the magicians’ circle but for the masses, he has faded into antiquity. Since magic, like any other performing art, relates to human life, Rahamatullah had used his magical art with a purpose, a meaning to touch and transform lives of people.

The Madaris usually carried multi-coloured quilt bags that contained knick-knack items like balls of different sizes, a few bowls, feathers, a ‘magic’ wand and human ‘bones’.

Rahamatullah was a familiar face in the city and his road shows attracted people of all ages. He had the ability to attract audience who observed him transfixed as he produced objects from ‘thin air’ with elan, transformed one object into something else, ‘vanished’ solid stuff like cups and saucers, generate miniature forms of gods from balls etc. in split seconds. Rahamatullah was passionate about his art but money was hard to come by. Madaris like Rahamatullah attracted a large crowd that dispersed as soon as a show ended and most viewers avoided paying for the shows. Money was never adequate to thrive on this business.

One day, Rahamatullah was going through his regular routine in an alley in Bhawanipore. After the show, he collected his props, folded the sheet of cloth he used as stage and counted his day’s earning -- a ‘princely sum’ of Rs 25 only. He was now all set to go home. As he started walking, he suddenly felt a pull on his kurta. A small kid was trying to attract his attention. When Rahamatullah turned around, the kid requested him to meet his grandparents who lived in a house nearby. There was an urgency in the child’s voice that melted Rahamatullah’s heart and he followed the child.

In the 1960s and 1970s, street performers, commonly referred to as Madari aka Jadoogar roamed the streets of the city, demonstrating myriad tricks and magical acts in the open at street corners. These roving magicians in their strange gypsy attires evoked both suspicion and reverence.

They reached a dilapidated house. The child rushed in to announce the arrival of a magician. He assured his grandfather that the magician would set everything right with his supernatural power of sorcery. Rahamatullah noticed an elderly lady lying in bed. She was ill and looked very frail. He realized the family had fallen on hard times. He began his show and in the pretext of showing tricks, he got fruits from ‘thin air’ one after another and kept piling them on a table. He fished out Rs five and then offered them all that he produced ‘magically.’ But the dignified couple refused to accept the gifts. At this juncture, Rahamatullah convinced them saying he was merely following the Almighty’s orders and the gifts were bestowed on them by God. He was merely a messenger. The couple now gladly accepted ‘God’s grace.’

In modern times, when earthlings have become mechanized, introverts, poor gypsies like Rahamatullah still teach us the basic duty of mortals – to stand by and empathize our fellow human beings and share their woes.