Letters to Remember: Celebrating Rishi Aurobindo’s 150th anniversary through his letters

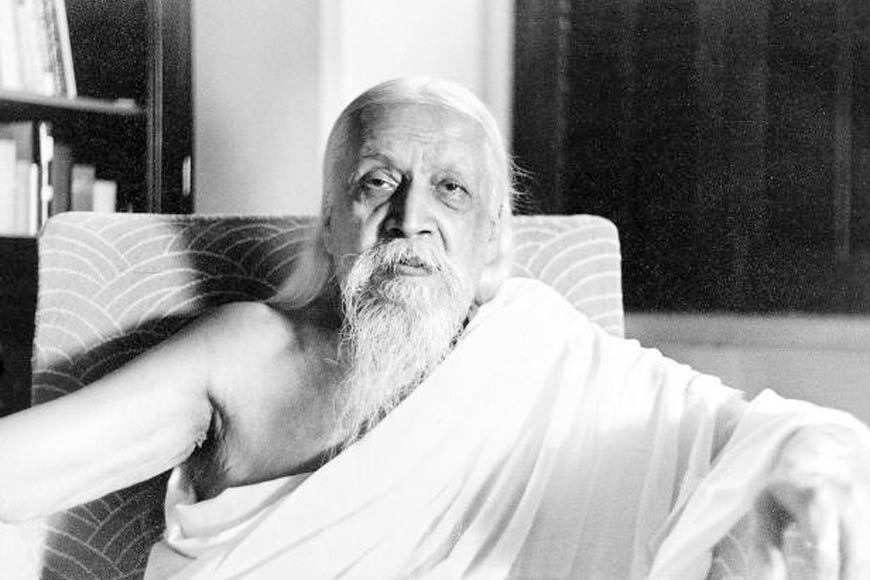

Aurobindo Ghosh was an extremely meritorious student and topped most examinations he gave. Even his British teachers were in awe of the English language he used to write essays. In the following letter written to his father, Aurobindo speaks on how his examiner, the well-known Oscar Browning praised him and his papers.

“Last night I was invited to coffee with one of the Dons and in his rooms I met the Great O.B. otherwise Oscar Browning, who is the feature par excellence of King’s. He was extremely flattering; passing from the subject of cotillions to that of scholarships he said to me, ‘I suppose you know you passed an extraordinarily high examination. I have examined papers at thirteen examinations and I have never during that time seen such excellent papers as yours (meaning my classical papers at the scholarship examination). As for your essay it was wonderful.’ In this essay (a comparison between Shakespeare and Milton) I indulged in my Oriental tastes to the top of their bent; it overflowed with rich and tropical imagery; it abounded in antitheses and epigrams and it expressed my real feelings without restraint or reservation. I thought myself that it was the best thing I had ever done, but at school I would have been condemned as extraordinarily Asiatic and bombastic. The Great O.B. afterwards asked me where my rooms were and when I answered, he said: ‘That wretched hole!’ then turning to Mahaffy he said: ‘How rude we are to our scholars! we get great minds to come down here and then shut them up in that box! I suppose it is to keep their pride down.’

Aurobindo once was very attached to his family. From Grandfather to sister, he wrote regular letters to all members of his family from faraway shores. Since he was educated in a British public school and later in the University of Cambridge where he became proficient in several European languages, Aurobindo did not know Indian languages till a certain age, which he later mastered including Sanskrit. In his letter to his grandfather he speaks of one such episode.

My dear Grandfather,

I received your telegram and postcard together this afternoon. I am at present in an exceedingly out of the way place, without any post-office within fifteen miles of it; so it would not be easy to telegraph. I shall probably be able to get to Bengal by the end of next week. I had intended to be there by this time, but there is some difficulty about my last month’s salary without which I cannot very easily move. However, I have written for a month’s privileged leave and as soon as it is sanctioned shall make ready to start. I shall pass by Ajmere and stop for a day with Beno. My articles are with him; I will bring them on with me. As I do not know Urdu, or indeed any other language of the country, I may find it convenient to bring my clerk with me. I suppose there will be no difficulty about accommodating him. I got my uncle’s letter inclosing Soro’s, the latter might have presented some difficulties, for there is no one who knows Bengali in Baroda — no one at least whom I could get at. Fortunately, the smattering I acquired in England stood me in good stead, and I was able to make out the sense of the letter, barring a word here and a word there. Do you happen to know a certain Akshaya Kumara Ghosh, resident in Bombay who claims to be a friend of the family? He has opened a correspondence with me — I have also seen him once at Bombay — and he wants me to join him in some very laudable enterprises which he has on hand. I have given him that sort of double-edged encouragement which civility demanded, but as his letters seemed to evince some defect either of perfect sanity or perfect honesty, I did not think it prudent to go farther than that, without some better credentials than a self-introduction. If all goes well, I shall leave Baroda on the 18th; at any rate it will not be more than a day or two later.

Your affectionate grandson Aravind A. Ghose.

While in England Aurobindo Ghosh happened to meet Maharaja Sawaji Rao Gaekwad III, the ruler of the princely state of Baroda who was on a visit to England. The Maharaja then 30, had made a name for himself as an extremely progressive native ruler. Through common friends, the Maharaja came across Aurobindo and was impressed by the 20-year-old young man who had chucked one of the most coveted service of the British empire and invited him to serve in the Baroda administration. Serving under a progressive Indian ruler was far more interesting to Aurobindo than doing so under the British crown. So Aurobindo set sail from England to Baroda. The following letter written to his beloved sister is a testimony of his stint at Baroda

Also read : Did Aurobindo Ghosh wish for an Akhand Bharat?

My dear Saro,

I got your letter the day before yesterday. I have been trying hard to write to you for the last three weeks but have hitherto failed. Today I am making a huge effort and hope to put the letter in the post before nightfall. As I am now invigorated by three days’ leave, I almost think I shall succeed. It will be, I fear, quite impossible to come to you again so early as the Puja, though if I only could, I should start tomorrow. Neither my affairs, nor my finances will admit of it. Indeed it was a great mistake for me to go at all; for it has made Baroda quite intolerable to me. There is an old story about Judas Iscariot, which suits me down to the ground. Judas, after betraying Christ, hanged himself and went to Hell where he was honoured with the hottest oven in the whole establishment. Here he must burn for ever and ever; but in his life he had done one kind act and for this they permitted him by special mercy of God to cool himself for an hour every Christmas on an iceberg in the North Pole. Now this has always seemed to me not mercy, but a peculiar refinement of cruelty. For how could Hell fail to be ten times more Hell to the poor wretch after the delicious coolness of his iceberg? I do not know for what enormous crime I have been condemned to Baroda but my case is just parallel. Since my pleasant sojourn with you at Baidyanath, Baroda seems a hundred times more Baroda. I dare say Beno may write to you three or four days before he leaves England. But you must think yourself lucky if he does as much as that. Most likely the first you hear of him, will be Letters of Historical Interest, a telegram from Calcutta. Certainly, he has not written to me. I never expected and should be afraid to get a letter. It would be such a shocking surprise that I should certainly be able to do nothing but roll on the floor and gasp for breath for the next two or three hours. No, the favours of the Gods are too awful to be coveted. I dare say he will have energy enough to hand over your letter to Mano as they must be seeing each other almost daily. You must give Mano a little time before he answers you. He too is Beno’s brother. Please let me have Beno’s address as I don’t know where to send a letter I have ready for him. Will you also let me have the name of Bari’s English Composition Book and its compiler? I want such a book badly, as this will be useful for me not only in Bengalee but in Guzerati. There are no convenient books like that here. You say in your letter “all here are quite well”; yet in the very next sentence I read “Bari has an attack of fever”. Do you mean then that Bari is nobody? Poor Bari! That he should be excluded from the list of human beings, is only right and proper; but it is a little hard that he should be denied existence altogether. I hope it is only a slight attack. I am quite well. I have brought a fund of health with me from Bengal, which, I hope it will take me some time to exhaust; but I have just passed my twenty-second milestone, August 15 last, since my birthday and am beginning to get dreadfully old. I infer from your letter that you are making great progress in English. I hope you will learn very quickly; I can then write to you quite what I want to say and just in the way I want to say it. I feel some difficulty in doing that now and I don’t know whether you will understand it.

With love, Your affectionate brother, Auro. .

(Source: Autobiographies and other Writings by Aurobindo Ghosh)