Kolkata People's Film Festival provokes thought, leaves memories

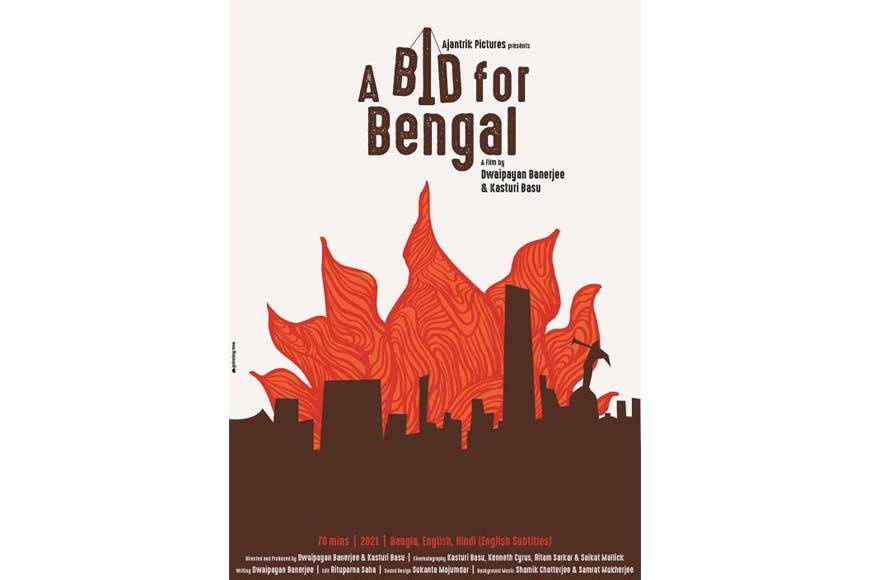

A Bid for Bengal

Having begun in 2014, the Kolkata People’s Collective recently hosted another edition of Kolkata People’s Film Festival. It has been multi-functional in spreading awareness through what it terms 'Pratirodher Cinema' (Cinema of Resistance), through screenings of films not only through an annual film festival but also month-end screenings and discussions, special cinema workshops for children from slums, and so on.

A Bid for Bengal

A Bid for Bengal

'Resistance' here is defined as “the act of resisting, opposing or taking a stand against a given philosophy, ideology, concept, act or practice”. Applied to cinema, it suggests films that take a stand against anything that violates human rights, child rights, or constitutional rights, as also against oppression and marginalisation of an individual or group of individuals based on class, opportunity, language, culture, earning avenues, and penury. Cinema of Resistance is more a movement than a festival, where the manner in which they are made often creates films that could be labelled political. It is an independent space that alternative and independent filmmakers have created, involving the total commitment of volunteers drawn from different fields of life such as academia, creative writing, cinema, and so on.

This year, the festival was held between March 31 and April 3 at Uttam Mancha, from 10.00 am to 9.00 pm. This festival stands out for many reasons. It does not charge an entry fee for viewers, and issues daily free coupons for those who wish to watch serious documentaries, short fiction from India and across South East Asia. Second, this festival is run entirely by volunteers who work without payment of any sort, cash or kind. Third, organisers of the PFC never accept funding or sponsorship from any government, non-government, or corporate body. A donation box is placed in the lobby where viewers are requested to put in whatever little they can to allow the festival to go on.

Uma Chakravorty

Uma Chakravorty

Kasturi, 38, and Dwaipayan, 38, are two of the founding members of People’s Film Collective, and have made some brilliant political documentaries themselves. The biggest draw at this year's KPFF was their 70-minute documentary, A Bid for Bengal, which explores, both in depth and in width and across time-belts, how the Hindu right, with its politics of caste, class, religion and gender, has become so strong in West Bengal after three decades of Communist rule. The actual footage of arson, lathi charge, forcing an old man to chant Jai Hind threatening him if he did not, beating up people who openly opposed their fanatic stance and much much more. The two directors have visited Hanskhali in Nadia and mainly focussed on the dramatic changes in West Bengal in general and Kolkata in particular.

Besides films, there is a daily display of posters, books, DVDs of fims, magazines etc offered for sale which focus mainly on human rights violations, violation of democratic and constitutional rights, violation of women, Dalits, minorities and so on.

The eighth edition screened 38 films featuring a wide range of compelling stories from the sub-continent. Due to the pandemic, this festival did not take place last year so this year witnessed quite a handsome collection of concerned filmmakers and an equally concerned audience.

Holy Rights

Holy Rights

Let us focus on some of the more significant films screened at the festival. Holy Rights by Farah Khatun depicts the irony of the conventional Muslim marriage in which the husband can divorce his wife just by uttering the word 'talaq' thrice – personally, over the phone, through email, WhatsApp and what not and the marriage is deemed null and void. What happens to the wife and children? How does she take care of the financial and social needs of the family without the support of the husband in a very patriarchal framework? The religious leaders actually sanction this practice though nowhere either in the Quran or in the Hadith is it mentioned that citing talaq three times can bring about a divorce with immediate effect.

In And We Were There, history professor and dedicated social activist Uma Chakravarti zeroes in on the first-person nostalgic experiences of 15 women prisoners arrested without any charge sheet or even FIR, during the political and rebellious upheaval that overtook different parts of the country between 1966 and 1971. Some are no longer with us. They had surrendered themselves, leaving home and hearth, to get sucked into the movement even when, towards the end, some of them realised that the movement is doomed to failure though the leaders were confident that they will be able to topple the present state of administration ruled by capitalist, feudal and dictatorial party power and establish people’s power. It is a very informative, educative and enriching film.

Boderlands

Boderlands

Samarth Mahajan’s 67-minute documentary Borderlands explores the lives of people who are forcibly settled in areas either very close to the border of a neighbouring country or between two borders of two neighbouring countries. This unfolds through the lives of four people spread across the film, living away from their native lands and trying to eke out a bare livelihood and adjust to the changed paradigms of their lives. The film is an in-depth journey of the director and his entire team through these borderlands and makes it a film not about places or spaces but about the people involved in this displacement which they did not desire but no one was asking! The film is produced by All Things Small and Camera and Shorts. It covers features five languages, and six locations — Imphal, Nargaon, Kolkata, Birgunj, Dinanagar and Jodhpur.

Also read : Uneasy ties: Student politics and cinema

Debalina’s 67-minute documentary Gay India Matrimony, with lovely touches of good humour and happy camaraderie, begins with the filmmaker trying to find out whether she can get married or not and if yes, being a person of alternative sexual preferences, gathers three young people with similar beliefs and lifestyles to find out how, in the face of Section 377 of the IPC which marks legal acceptance of same-sex couples but not marriage, they can marry and if they do, what will be the implications – within the family, the society and their large lives beyond their immediate circle.

Gay India Matrimony

Gay India Matrimony

Can they marry? Since legal sanction is ruled out by the Supreme Court itself, three individuals discuss, along with a whole lot of others, whether marriage between homosexual couples should be legal, social or a matter of individual choice. It is a delightful film that also touches upon Marx and Engels’ perspectives on private property and one feminist professor’s views on marriage per se. Interestingly, this film was produced by Films Division and Sappho for Equality, a NGO for same-sex attuned people, lent support.

Among the short films, Anonymous (25 minutes) directed by Mithunchandra Chaudhari steps into the anonymous lives of the marginalised, underpaid and severely exploited construction workers whose names we never get to know. A strong indictment on the generally accepted invisibility of a large section of labourers who form the most important part of the construction business in the country.

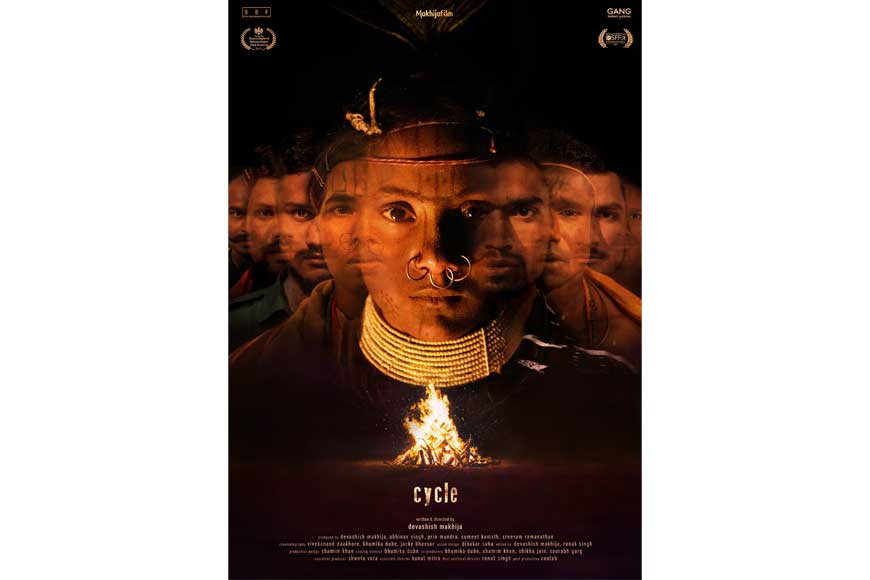

Cycle Poster

Cycle Poster

Akshay S.Poddar’s short film Aruna is a lovely, low-key and almost silent tracking of the life of Aruna, a married woman whose husband is always on tour, leaving her alone to face life, difficult what with a young man trying to woo her awkwardly, or a younger cousin invited her for a home-stay to make her cook for her and her boyfriend finally making her walk away leaving whatever little life she had, behind.

Devashish Makhija’s Cycle is shot on a phone camera as found footage, and filmed in three uninterrupted long takes. The film features a large and ethnically varied cast, most of whom were facing a camera for the first time ever. According to the young director, “though Cycle is a genre film of rape and vengeance, what we seek to do along the way is to suddenly thrust upon a bloodthirsty audience – the idea of anti-vengeance. And to deny the viewer any brutal satisfaction they expect and seek from a narrative of this kind”.

These were films that left a mark on this writer. Thanks to KPFF.