Kolkata girl offers first peek into Indus Valley language mystery

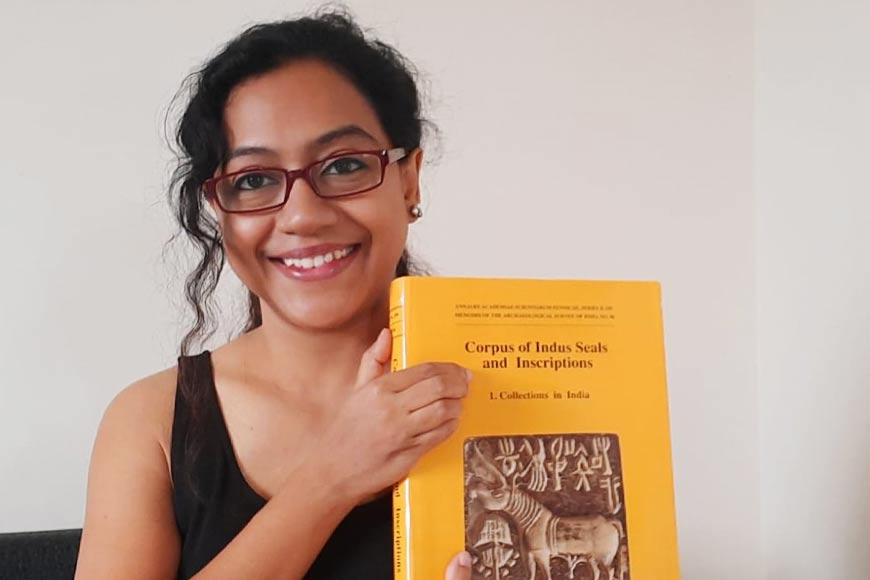

A collection of intriguing pictographs on seals, on shards of pottery, on tablets, on ivory rods. Clearly indicating a pattern, but tantalisingly out of reach when it comes to decoding what they meant. For decades, this has been the status of the inscriptions found on more than 4,000 objects unearthed across various excavated sites belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), which lasted from roughly 3300 to 1300 BC.

While it seems inconceivable that citizens of a such an advanced and far-flung civilisation (covering 680,000-800,000 sq km of the subcontinent at its height) had no modes of written communication, all that has come down to us are the aforementioned inscriptions, which the ablest of scholars have thus far failed to decipher.

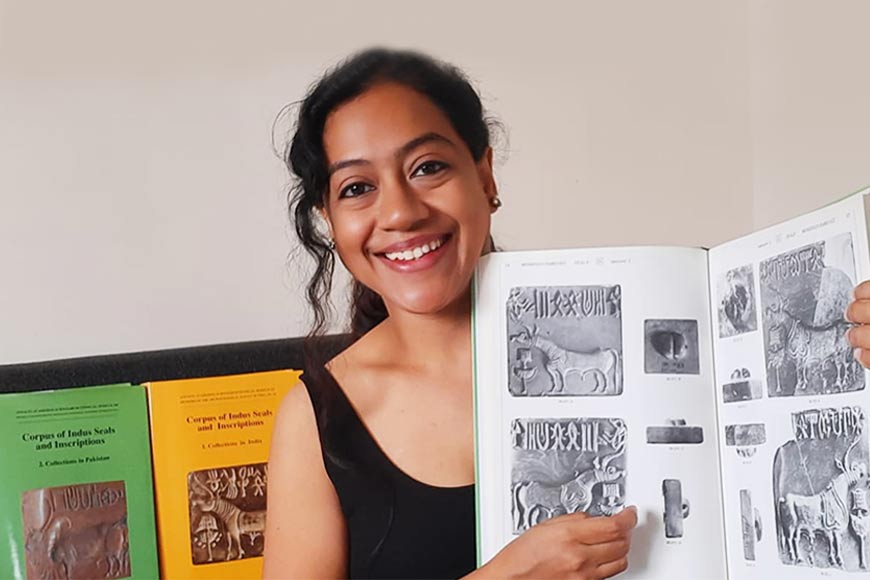

This is the task that Bahata Anshumali Maukhopadhyay, a software technologist who lives and works in Bengaluru, has been focusing on since 2014. And in 2019 and 2021, this alumnus of Kolkata’s Sister Nivedita Girls’ School submitted what could well become two groundbreaking papers to Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, a publication from the internationally renowned Nature group.

Bahata’s second paper in particular has begun to cause a stir in the media. In very basic terms, it is the first time that any researcher has come forward with a particular word used by the IVC people - the word being ‘pilu’, an ancient Dravidian word for elephant, derived from the root word for tooth/tusk called ‘pal’ and its alternate forms (‘pīl’/‘pel’). This has led her to conclude that our ancient forebears from the IVC spoke a proto-Dravidian language, a possible ancestor of the Dravidian group of languages still spoken today in southern India.

How she arrived at this conclusion is explained in detail in her paper titled ‘Ancestral Dravidian languages in Indus Civilization: ultraconserved Dravidian tooth-word reveals deep linguistic ancestry and supports genetics’. That’s quite a mouthful, and the entire scope of the paper is well beyond the scope of this article, but it ought to be enough to explain that Bahata found that the words for elephant (in Bronze Age Mesopotamia) and ivory (in Old Persian documents from 6th century BC) are linked to words currently used in modern-day Dravidian languages, all of them derived from the ancient Dravidian root word.

A software technologist who doubles as an IVC scholar? Bahata attributes this strange combination to her love of science and scientific inquiry. “I approached the issue from a common sense perspective, and it perhaps helped that I had no formal training, which would probably have limited my scope,” she explains. Having begun her work on the IVC script in association with a Cambridge University professor, she is now entirely on her own, though her work has put her in touch with some of the most renowned IVC experts around the world.

The second paper is essentially an offshoot of the first published in 2019, which was titled ‘Interrogating Indus inscriptions to unravel their mechanisms of meaning conveyance’. Looking beyond the title, the simple meaning would be - what do the Indus inscriptions really convey? Bahata’s contention is that the inscriptions were primarily mercantile or commercial in nature, and the progress made in that area has led her to her second discovery.

Also read : Naren Hansda – Pied Piper of Purulia

As Bahata writes in her second paper, “The logic is that when we import a foreign commodity not locally produced, we usually call it by its foreign name. This intuitive approach has been duly rewarded, as it is found that the words ‘pīru’/‘pīri’ and their various dialectal variations, which signified elephant in Akkadian and ivory (‘pīrus’) in Old Persian, are perfect tools for the present endeavour…In several Dravidian languages, ‘pīlu’, ‘pella’, ‘palla’, ‘pallava’, ‘piḷḷuvam’, ‘pīluru’, etcetera, signify elephant.”

While anyone with a basic knowledge of Indian history knows that the IVC people enjoyed a flourishing trade with Mesopotamia and its adjoining regions, how did it occur to Bahata to look to them for clues about the IVC script and language? “In the absence of any documentary evidence, I thought of looking to the people the IVC traded with, hoping to find words in their documents borrowed from their trade partners,” she says.

She has found other reinforcements for her argument in favour of this word originally belonging to the IVC region. “The word ‘pilu’ describes not merely the elephant, but also the Salvadora persica tree, known as the toothbrush tree, which was called ‘pīlu’ following the decline of IVC. One other tree that was called pilu is the Careya arborea (common English names include wild guava, Ceylon oak, patana oak), whose fruit is highly favoured by elephants, also indigenous to the IVC region. That cannot be a coincidence,” she says.

Very excitingly, Bahata has made several more inroads into the hitherto indecipherable IVC script, and thinks she has found words to match the pictographs, but will only talk about her findings once they are published. Her passion for this particular task had once led her to quit her job for nearly a year so that she could focus on her research. Given this level of dedication, more pathbreaking results are surely only a matter of time.