Kolkata breaks new ground, hosts India’s first solo AI art exhibition

Actor-producer Rituparna Sengupta, curator Myna Mukherjee, artist Harshit Agarwal, and filmmaker Ranjan Ghosh at the inauguration

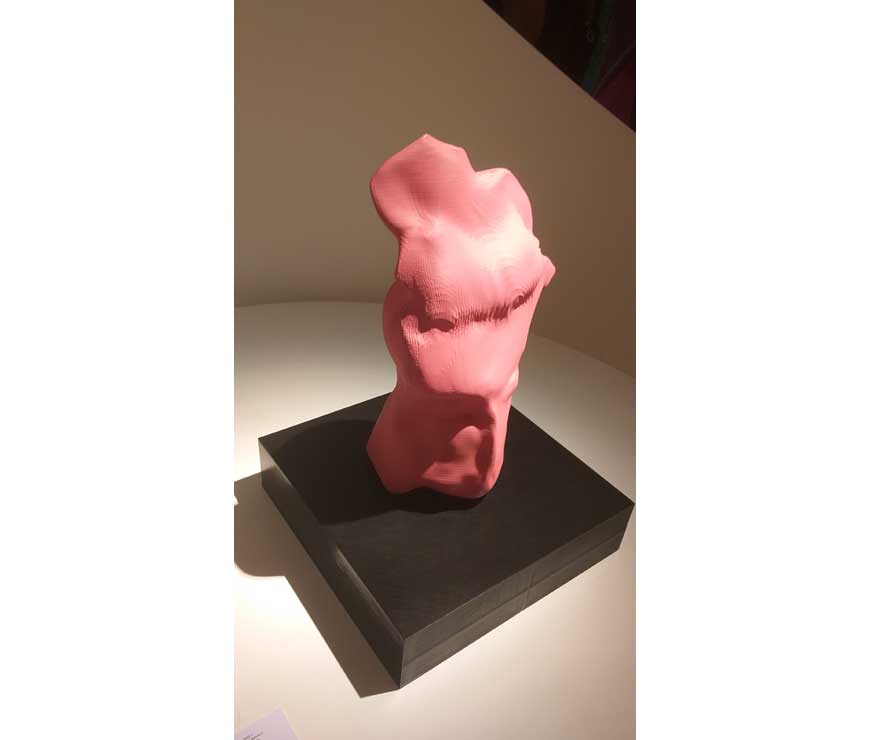

The man vs machine debate is now more than a generation old. So we’re not going there. However, walking through Harshit Agarwal’s fascinating art exhibition titled ‘EXO-Stential – AI Musings on the Posthuman’ at Emami Art, Kolkata Centre for Creativity (in Anandapur, off the EM Bypass), one does wonder whether creativity, like many other facets of our lives, will gradually be taken over by machines too.

That, of course, is a completely lay person’s way of looking at things. The 29-year-old artist’s show, curated by Delhi-based Myna Mukherjee, is India’s first ever solo exhibition of art produced entirely by Artificial Intelligence (AI), in which a machine or group of machines are trained to recognise thousands of shapes and colour patterns to produce works of art that quite easily transcend the boundaries of what the ordinary viewer would call imagination.

The project is supported by Engendered, a transnational arts and human rights organization of which Mukherjee is the director, and is in collaboration with 64/1, an art collective founded by brothers Karthik Kalyanaraman and Raghava K.K.

Writing on Instagram, Agarwal, a graduate of IIT Guwahati and Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab, has this to say about the exhibition: “Bringing together my #AI art practice of over 6 years since the inception of this field. Spanning themes beyond the novelty hype to explore themes of authorship, gender perceptions, deep rooted social inequities and biases, identity, seemingly universal notions of the everyday- all through this new lens of AI with its unique capabilities of complex data understanding and estrangement. Let’s engage consciously with this beast we’re increasingly being immersed in, journeying into the #posthuman, instead of being simply sucked into it!”

At its most basic, a piece of AI art is created when an artist writes algorithms with a certain visual outcome in mind. These algorithms provide broad directions and allow a machine to ‘learn’ a specific aesthetic by analysing thousands of images. The machine then creates an image based on what it has learned. As Agarwal says, “AI’s usage in art elevates it from being simply a tool for execution – it influences the outputs more heavily by its estrangement of the dataset it learns from (under the direction and instrumentation of the human artist). I find this space of engagement with the machine fascinating to work with.”

Mukherjee adds, “As a curator, what strikes me most about Harshit’s work is that it consciously engages with this inevitable techno-centric reality we live in. It allows us to witness how humans can work with machines to enhance their creativity, rather than allow their creativity to be replaced by mechanical labour. For example, one of the works uses AI facial recognition technology that is typically used for profiling and identifying criminal activity, to create a conceptual art piece that instead builds empathy toward deep-rooted social inequalities in the Indian tradition.”

She is referring to ‘Masked Reality’, an interactive video in which you, the viewer, will see your facial expressions transformed into those of a female Kathakali performer juxtaposed simultaneously with that of a male Theyyam (a ritual dance from Kerala) exponent. The first algorithm which Agarwal has created breaks down the structure of any video image of a face that it sees into the basic facial structure, and the second learns to add the appropriate face paint to transform it into the face of a Kathakali or Theyyam performer.

The ‘social inequalities’ that Mukherjee talks about have to do with the fact that while Kathakali is patronized by royal families and ‘sattvic’ temples where Dalits typically had no entry, Theyyam is performed typically by the lower castes. In making you a participant in this juxtaposition, Agrawal asks important questions about the role of technology in the process of defining/preserving ‘cultural heritage’ and about the fuzzy space between appropriation and creative borrowing.

Dr Debanuj Dasgupta, Assistant Professor of Feminist Studies at University of California Santa Barbara, was one of the guests at the inauguration. “This very well curated exhibition provokes important conversations. Two pieces I found particularly fascinating as a gender studies scholar were the ones based on stick figures of male and female figures, which Harshit fed to AI, and the AI apparently recognised the female principle more accurately over the male. He then had to assign a male-female binary to the figures, but I find it significant that the AI doesn’t necessarily give back a binary, instead preserving a continuum. Which shows how the gender binary is a medical and social construct,” he said.

Why choose Kolkata for this very important exhibition? As Mukherjee explains, “I was shooting for a documentary which caused me to focus on Santiniketan and Baroda as centres of art, and it struck me that Santiniketan and by extension Bengal has been responsible for some of India’s greatest names in art. But the space has been vacant for a while, and I wanted to bring Bengal back into the conversation about cutting edge art, which is where I feel it deserves to be.”

The exhibition is on at Emami Art until September 30, 11.00 am to 6.00 pm