Kali and Bengal’s legendary dacoits, an everlasting bond

Dacoit or dacoity are not words you will find in any standard English dictionary, even today. They are a peculiarly British-Indian coinage, originally intended for legal use only, from the Hindi/Urdu ‘dakait’ (robber or bandit), also the origin of the Bengali word ‘dakat’. So pervasive was the phenomenon of armed banditry in the 19th century that the East India Company actually established a Thuggee and Dacoity Department in 1830, and passed the Thuggee and Dacoity Suppression Acts, 1836-1848.

But like bandits in many other cultures, such as Robin Hood in 13th or 14th century England or the Ned Kelly gang in 19th century Australia, the dacoits of Bengal have not remained mere outlaws. Over the centuries, they have been romanticised and shaped into the stereotype of the ‘noble and chivalrous bandit’, a social deviant or popular protestor who sought to overturn an exploitative rural economic system, striking a blow against British rule and its Indian enablers in the process. The reality was rarely as simple, but that is a discussion for another day.

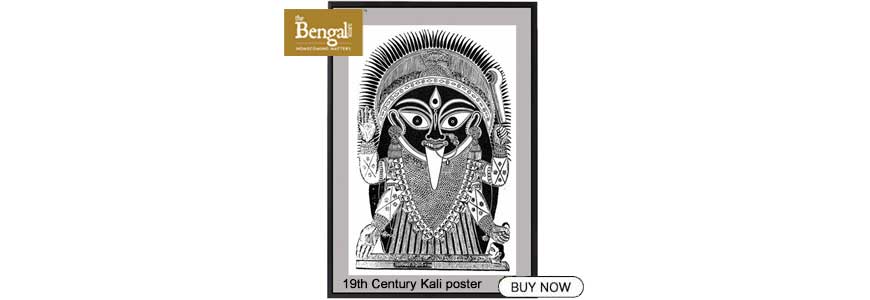

The one other thing that Bengal’s dacoits are remembered for is their allegiance to Kali, goddess of ultimate power, time, destruction and change, which is why you are reading this article on Kali Puja.

From available records and writings, it appears that dacoity was most rampant in Bengal from 1841-57, particularly in the districts of 24 Parganas, Howrah, Hooghly, Bardhaman, Nadia, Murshidabad, Jessore (now in Bangladesh) and Medinipur. The curve reached a peak in 1851 with 524 recorded cases, and fell to 92 by 1856, according to a 2007 article by Suranjan Das in Economic & Political Weekly. Understandably, these were the districts most famed for Kali Pujas organised by dacoits, with many of them surviving to the present day.

Kolkata itself is home to a puja instituted by the modern day Robin Hood Fatakeshto, born Krishnachandra Dutta, who rose to great prominence from the 1960s onward. His Naba Jubak Sangha club organised the Kali Puja which drew the support and participation of several renowned celebrities of the day, including megastar Uttam Kumar. It remains one the city’s grandest Kali Pujas to this day, and Fatakeshto has been the subject of two films bearing his name, both smash hits directed by Swapan Saha.

Historically, the most common narrative that has been handed down to us is the one of dacoits performing their devotions to Kali under cover of darkness, seeking her blessings before every major ‘mission’. Sacrificial offerings to her ranged from animals (mostly goats) to humans, a horrifying practice which was quite widely recorded.

But many of them were daily worshippers of Kali, not needing an occasion to express their devotion. Take the example of Raghunath Ghosh or Raghu Dakat, the legendary terror of the Bansberia region in Hooghly in the mid-1700s. So well known was his dedication to Kali that he has been credited with instituting Kali temples and pujas across the state, their original founders long forgotten. Nonetheless, the two pujas he does seem to have begun are the ones in Basudebpur and Tribeni. One of his practices was to offer a daily tribute of roasted ‘lyata’ fish (Bombay duck, a species of lizardfish) to the goddess, a practice that continues to this day.

The temple to Bama or Vama Kali (also called Samhara Kali, the most dangerous and powerful form of the goddess as she steps out with her left foot holding her sword in her right hand) in Panduk, Bardhaman (West) was established by Prahlad Dakat, whose life is shrouded in mystery. The story told today is that he set up the temple following a robbery in Ketugram, during which one of his gang members assaulted a woman, violating the code of not harming women which many dacoits apparently adhered to. A furious Prahlad killed the man, upon which the lady assumed the form of Kali. And thus a temple was born.

Another interesting example comes from Jirat in Hooghly, where Kele Dakat established a temple to Siddheswari Kali, with the core structure of the idol having remained unchanged over the centuries. By day, Kele Dakat was apparently wealthy zamindar (landowner and tax collector) Kalichand, and much of his wealth came from his alternative ‘profession’. Kalichand’s descendants have always denied this story, though it remains a recorded fact that many of Bengal’s famous robbers did seek to earn social respectability as zamindars.

Staying in Hooghly, a famed Kali Puja is that of Gagan Dakat, who apparently operated in the area we know as Singur. Part of the folklore surrounding Gagan is his practice of terrorising wealthy and influential Bengalis who collaborated with the British. The story of how he found Kali is quite fantastic, involving yet another legendary name, that of Sarada Devi, wife of Shri Ramakrishna Paramhansa, perhaps Bengal’s most iconic Kali worshipper.

One evening, Sarada Devi was apparently on her way to see her husband when Gagan Dakat and his men attacked the travellers. But a shocked Gagan began to see manifestations of Kali in Sarada Devi, as her eyes turned bloodshot and her face began to change. Terrified, he fell at her feet and begged her to stay the night at his home. For dinner, she was offered ‘chal bhaja’ (fried grains of rice) and ‘korai/kolai bhaja’ (fried black gram). Soon after, Gagan Dakat established his Kali temple, where the goddess is still offered chal and korai bhaja.

The name of Raghu Dakat is sometimes added on to this story for good measure, as his and Gagan’s territories probably often overlapped, but there is no historical record for any of it. In fact, Bengal’s famed dacoits have found very little representation in history apart from official records of their misdeeds and sometimes capture. What there are, are the Kali Pujas themselves, and the stories handed down through generations. Even if none of it is true, we shouldn’t, as Mark Twain once famously said, let facts get in the way of a good story.