K.G. Subramanyan’s Legacy: An artist who spanned worlds and generations - GetBengal Story

I first met the renowned artist K. G. Subramanyan—whom we all fondly called Manida—on August 25, 1996. I remember the exact date because that day, he signed a book written about him and noted the date beside his signature. The last time I saw him was on June 25, 2016, just a few days before he passed away.

Over those twenty years in between, I had the chance to talk with Manida many times about art. In the early years, our conversations took place in Santiniketan, and later in Baroda (currently Vadodara)—sometimes in the Fine Arts studio at the university, sometimes at exhibitions, and quite often at his home in Baroda.

In the later years, we lived in the same neighbourhood, and I became his neighbour. During that time, I would often drop by his house in the evenings just to chat. Manida loved to tell stories. Most of the time, I would simply bring up a topic and then quietly listen. He would talk about an amazing world of art and memories—and as he spoke, it all played out in my mind like a film.

In his stories, great artists like Nandalal Bose, Ramkinkar Baij, and Binodbehari Mukherjee would appear as naturally as neighbours walking by. He would also recall experiences from before his days in Santiniketan;, sharing memories of the Madras Art College, and speaking of figures like its principal, Debiprasad Roy Chowdhury and K. C. S. Paniker.

I once asked Manida why and how he, someone born in the Malabar region of South India, ended up in Santiniketan, driven purely by his love for painting. His answer was deeply connected to the story of how he shaped himself as an artist.

In the mid-1930s, his family moved to the small town of Mahe, which was then a French colony. As a schoolboy, Manida began visiting the public library there regularly. Because it was under French rule, the library received some French magazines. One of them was L'Illustration, which often featured reproductions of artworks by modern European artists, as well as Japanese woodblock prints and African sculptures. These images deeply fascinated young Manida.

At the same time, the library also subscribed to English publications like Modern Review and Visva-Bharati Quarterly. Reading these introduced him to the world of Santiniketan and its unique artistic environment. He was especially drawn to the works of Rabindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose, which left a lasting impression on him.

Although he continued to draw on his own, he hadn’t seriously considered studying art. In 1941, Manida enrolled as an Economics student at Presidency College in Madras. But it was a politically charged time in Indian history, and he couldn’t stay untouched by it. He became actively involved in Gandhian politics, and in 1942, during the Quit India Movement, he was arrested and imprisoned as a student leader.

After his release, when he returned to college, his name was already on the British government’s list of suspects. Around this time, he began losing interest in formal academics and felt a stronger pull toward art.

It was during this phase that a few of his drawings reached artist K. C. S. Paniker, who then showed them to Debiprasad Roy Chowdhury, the principal of the Madras Art School. That moment turned out to be a key turning point in Manida’s artistic journey.

After seeing his drawings, Debiprasad Roy Chowdhury personally invited Manida to leave Presidency College and join the Madras Art School as a student. But by then, Manida’s elder brother had already written to Master Nandalal Bose, telling him about his younger brother’s deep interest in art and Santiniketan.

In his reply, Nandalal Bose said that if Manida came to Santiniketan, he would be happy to admit him to Kala Bhavana as a student. So, in 1944, Manida chose to follow his heart and began his journey to Santiniketan, turning down Debiprasad’s offer.

However, because of his involvement in student politics, the British police were keeping an eye on him. When they saw he was heading to Bengal, they suspected he was going to join the Medinipur revolutionary group. So, as soon as the train reached Cuttack station, the police boarded the train and began searching his belongings.

They didn’t find anything suspicious, so they got off a while later. But once the other passengers in the train compartment found out that Manida was a freedom fighter, they immediately offered him a proper seat and began treating him with great respect, sharing food and water, and showing their admiration in every way they could.

During one of our evening conversations, Manida shared this story with me. He said that from reading Modern Review in the Mahe library during his school days, to meeting Debiprasad Roy Chowdhury, and finally being suspected by the police of joining Bengal revolutionaries on his way to Santiniketan—somehow, life kept connecting him to Bengal in unexpected ways. This connection found its true meaning when he finally became a student at Kala Bhavana.

It's important to know Manida's early journey to truly understand how he developed his unique artistic language. While living in Mahe, he was almost simultaneously exposed to modern European art and Santiniketan’s artistic world. He also became familiar with Japanese, African, and other global art forms.

Interestingly, long before Manida arrived at Santiniketan, thanks to Rabindranath Tagore’s vision and the lectures of Stella Kramrisch, the teachers and students there were already introduced to various modern European art movements. At the same time, Nandalal Bose, through his own deep curiosity, had brought students close to Far Eastern, Egyptian, and other world art traditions.

In the years that followed, Nandalal grew more interested in classical Indian art as well as indigenous pattas, patas, etc.. He began incorporating techniques from Jain manuscripts and Bengali scroll paintings into his own work. He even learned Rajasthani fresco methods from Ustad Narsingh Lal, along with his students.

It was in this vibrant, multi-layered atmosphere that Manida’s art education truly began. Just before this period, Nandalalbabu had completed his famous Haripura poster series, and Ramkinkar Baij had created the open-air sculpture Santhal Family—works that stood as powerful examples right before Manida’s eyes.

At the same time, Manida also carried with him vivid childhood memories of seeing brightly painted wooden puppets back in Malabar. All of these experiences started blending within him, and in Santiniketan’s open learning environment, his personal sense of art slowly began to take shape.

A few years later, when Benodebehari Mukherjee planned his large mural of Medieval Saints across three walls of Hindi Bhavana, Manida stepped in to assist him. In Manida’s own words, being a part of that project was a tremendous learning experience.

While working on the mural, Benodebehari would discuss everything with him—the structure and composition of the painting, how to use multiple perspectives in a single frame, and how to draw from different world art traditions and make them your own. These deep discussions clearly influenced Manida, and we can see their reflection in his later works.

Interestingly, on the very day I first met Manida in 1996, after a conversation about my own work, he gave me some thoughtful advice and then sent me straight to Hindi Bhavana. He told me to carefully study Benodebehari’s art. I still remember climbing up onto a high bench to take a closer look—that experience became a powerful lesson for me, too.

One of the special qualities of the art education developed in Santiniketan under Nandalal Bose was the effort to bridge the gap between fine arts and crafts. As a result, alongside painting, sculpture, and printmaking, students also learned batik, leatherwork, Alpana (folk floor art), woodwork, and more. Rabindranath Tagore himself was very interested in this integrated approach to art education.

Nandalal was especially passionate about bringing art closer to ordinary people. There’s even a story that once he left some of his paintings at a local grocery shop to be sold at very low prices, just so that anyone could afford to buy them. But when his teacher, Abanindranath Tagore, found out, he reportedly bought up all the paintings himself!

This idea of making art accessible to all eventually led to the creation of the Karusangha, an organization that supported the making and selling of affordable art and crafts for the common people.

This philosophy deeply influenced Manida as well. His work found expression in many forms—painted wooden toys, decorated earthen bowls, illustrated books for children, prints on enamel plates, and more—especially during events like the Fine Arts Fair in Baroda and Nandan Mela in Santiniketan.

Manida’s handcrafted toys—made from wood, leather scraps, or other found materials—often reminded one of Abanindranath’s "Kutum Katam", whimsical creations made from household odds and ends.

Personally, I consider myself lucky that, as a student in Baroda, I had the chance to collect some of Manida’s handmade toys and children’s books at very modest prices. They remain treasures to me, both for their artistic charm and the values they represent.

Before joining as a teacher in Baroda, Manida spent some time working in textile design. During that period, he gained deep knowledge of traditional Indian patterns and motifs. Later, this understanding became beautifully visible in his paintings, murals, and illustrations for children's books.

While many of his contemporaries followed the structural and visual approaches of modern European artists, Manida took a different path. He used his knowledge of traditional textile design to create works that, while modern in concept, carried a strong and authentic Indian identity.

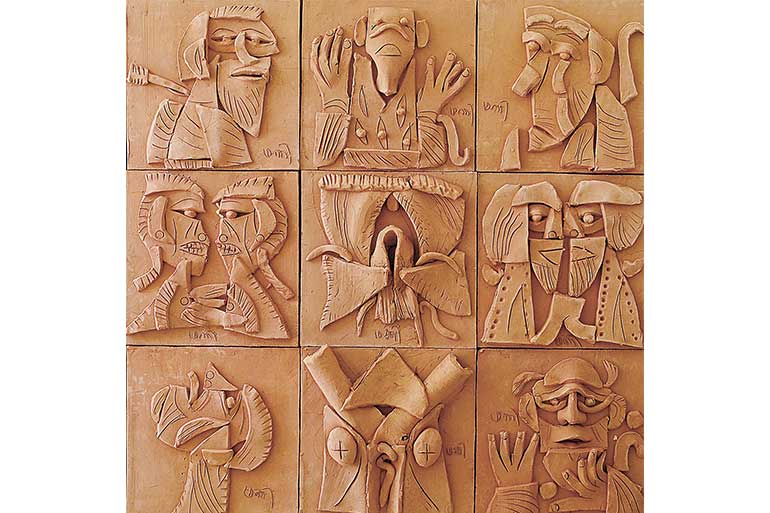

When he created large murals by assembling reliefs on terracotta tiles, he merged the styles of Bengal’s Bankura with that of Molela in Rajasthan, blending them with his own modern sensitivity. This resulted in a visual language that was entirely his own.

Alongside this vast quantity of creative work, Manida continued to write about art. His writings were not just theoretical discussions, but reflections drawn from the hands-on experience of a master practitioner.

I still remember—back in 1995, as a student, I happened to come across his book, Moving Focus. Reading it made a deep impression on me, and it was this very book that inspired me to reach out to him personally.

As a person, Manida was someone of immense patience. Even as a young student asking him all sorts of naive questions, I always found him willing to answer, coming down to my level of understanding, and never making me feel small.

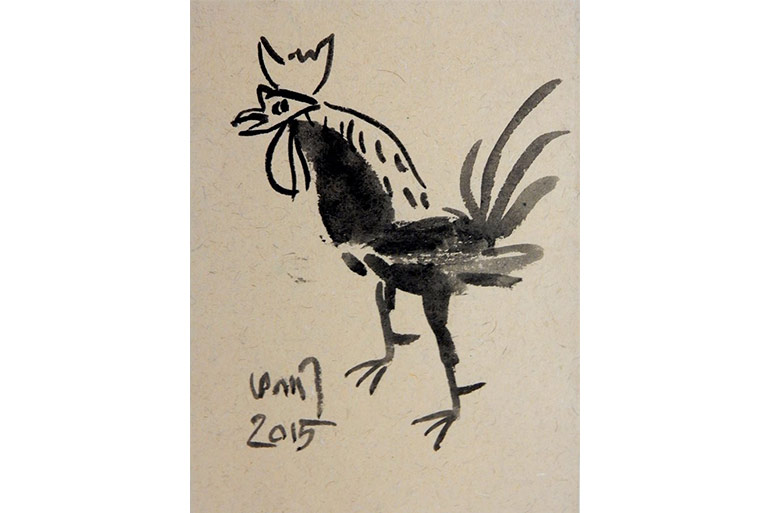

Contextually, we all know about the tradition in the Tagore family of sending letters and greetings through hand-drawn postcards and illustrated messages. Following that same spirit, Nandalal Bose, too, would send painted postcards to his students and loved ones. Manida, too, carried on this tradition all his life. Every year, he would draw small artworks on paper, write personal greetings, carefully put them in envelopes, handwrite the names and addresses himself, and post them to those close to him. I, too, would receive one every year, always just after Diwali. I have kept not only the little artworks but also the torn envelopes, each handwritten with my name and address—precious tokens of his warmth.

In his later years, I would teasingly ask him, “Manida, are you going to hit a century?” He would smile and reply, “Yes, I think I just might.”

In the end, that century didn’t happen. But now, as we mark his birth centenary, there are moments when I can hardly believe I had the chance to know and learn from such a great artist during his lifetime.