June, the month of the ‘Black Hole tragedy’

Walking or driving through Kolkata’s BBD Bagh area, the magnificent General Post Office (GPO) building is hard to miss. It has been part of the city landscape forever, or so it seems. In reality, the GPO was only designed in 1864 by Walter Grenville, but the land on which it stands was actually the site of the first Fort William, the one which Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah attacked in June, 1756. As we begin the same month 265 years later, the intense heat and humidity bring to mind a tragedy forever associated with that attack, the so-called ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’.

A narrow lane beside the GPO building was allegedly the site of a small guardhouse which became the notorious Black Hole. We say ‘allegedly’ because all the information we have about the incident is based on a report by army officer John Zephaniah Holwell, the only eyewitness account that has come down to us in writing. Considering the apparent scale of the tragedy, it seems strange that no other contemporary chronicler, British or otherwise, saw fit to write about it.

Since the Black Hole tragedy is familiar to many readers, it would be enough to state the basics - on the night of June 20, 1756, nearly 150 British and Indian prisoners (including Holwell) were held captive in a 14 x 18 feet room by soldiers belonging to Siraj-ud-Daulah’s army. Fort William had fallen to the nawab, and British reinforcements had failed to arrive. Crammed into that hot, stuffy, small room, the prisoners were given neither food nor water, and when the doors were opened in the morning, 123 of the 146 captives had died of suffocation and heat exhaustion, claimed Holwell.

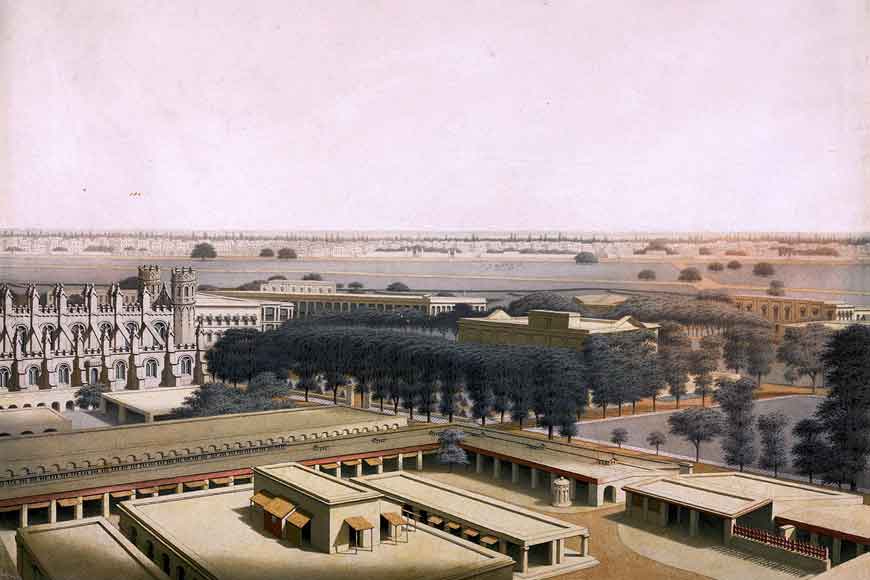

First Fort William - Kolkata

First Fort William - Kolkata

While it is fairly certain today that Holwell was exaggerating the scale of the tragedy, it is also equally true that something of this nature must have occurred on that June night. Later historians have stated that the number of prisoners was probably no more than 65, with around 45 deaths. Even if this were true, it is horrific enough. Curiously enough, Holwell and other British officials were sure that Siraj had played no part in the tragedy, and that the orders to imprison the captives in that room had not come from him.

Curious, because the backdrop to the Black Hole tragedy had much to do with Siraj’s personal animosity toward the British. Aware of Britain’s intention to set up colonies across the world, Siraj resented both the presence of the East India Company’s army in Bengal, as well as its growing political clout. He was also infuriated by the strengthening of the fortification around Fort William without his approval, and claimed that the British were abusing the trade privileges granted them by the Mughals, which was causing heavy financial losses to the government exchequer. Moreover, the British were providing shelter to corrupt officials like Krishnadas, who had fled Dhaka after embezzling government funds.

When the Company began further enhancing its military strength at Fort William, Siraj ordered it to stop. The Company ignored his directives, and Siraj marched on Calcutta.

In her 1905 book ‘Calcutta Past and Present’, Kathleen Blechynden wrote, “When news of the nawab’s intentions reached Calcutta, the unfortunate English there were thoroughly alarmed. The long years of security had made them careless; the Fort, never very strong, had fallen into disrepair; the defences were dominated by the church, and by the private houses of the merchants, that of the Governor in Bankshall Street, of Mr. Eyre about the middle of Fairlie Place to the north of the Fort, and of Mr. Cruttenden to the north of the church, at the junction of Lyons Range with Clive Street; while the thickly populated native town, spreading far to north and east of the Fort, was a source of serious danger.”

Though surrounded on three sides by Siraj’s 50,000-strong army, the British still had access to the river, and the fort’s governor and most of its senior officials eventually escaped by boat when defeat seemed certain, “leaving to their fate a greatly reduced garrison of brave men under John Zephaniah Holwell, the senior officer left on shore, whose courageous conduct has imperishably associated his name with the story of the Black Hole”, wrote Blechynden.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, the British erected a 15-metre obelisk which now stands in the graveyard of St. John’s Church in BBD Bagh. The obelisk was originally erected in 1901 on the orders of Lord Curzon at the corner of BBD Bagh, but removed in 1940 at the height of the Indian independence movement, under pressure from various Nationalist leaders, including Subhas Chandra Bose. The Black Hole itself, or the guardroom in the old Fort William, disappeared shortly after the incident when the fort itself was taken down and the new Fort William built on a part of the Maidan.

As for Siraj, his control over Calcutta proved short-lived. Indeed, he was to lose the whole of his kingdom at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, but that is another story.

GPO Image Courtesy Click Here

Fort William Image Courtesy

By User Rudolf 1922 on sv.wikipedia Click Here

Public Domain Click Here