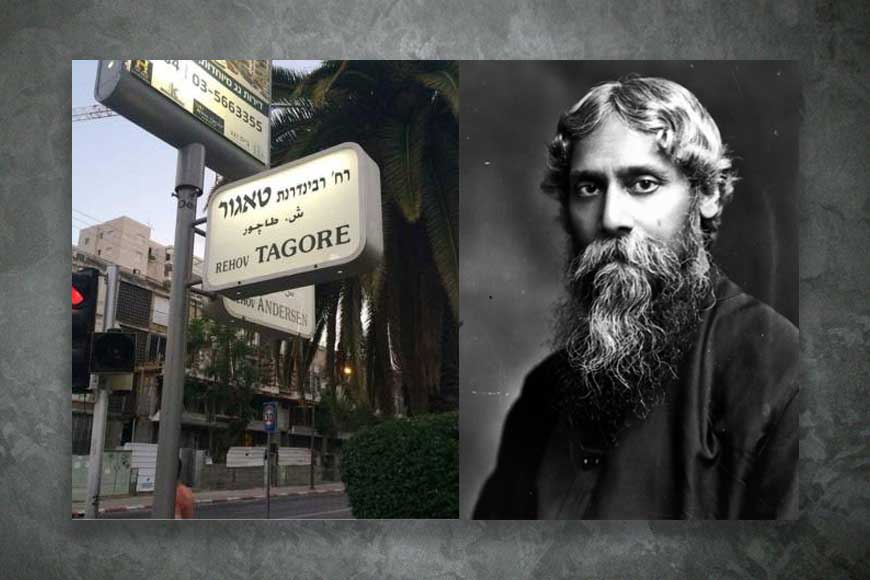

Israel names street after Tagore; GB traces Jewish connect of Rabindranath

On the 159th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore, Israel paid him a heartwarming tribute by sharing a picture of a street named after him in Tel Aviv. The street starts right opposite the main gates of Tel Aviv University and is now named as Tagore Street. In 1961 on his 100th birth anniversary, another street in Israel was named after him. Tagore’s connect with Israel and the Jews goes back to his creative days and his close relationship with many artists, authors and scientists of Israel.

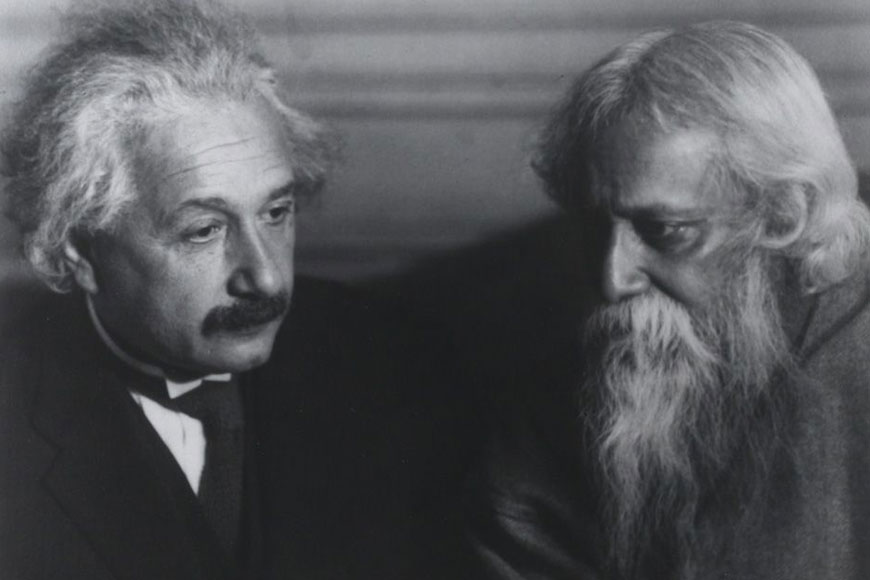

The great scientist Albert Einstein is even said to have privately called by the punning name of ‘Rabbi’ Tagore. They met and discussed on science and philosophy, one of the most talked about discussions in the world. The fact that there is an important street named after him in the world’s only Jewish state, Israel, is only a little hint of the respect he came to command among the Jews and his close association with some of them, the most prominent being Albert Einstein, Sir William Rothenstein, Alex Aronson, Moriz Winternitz, Sylvain Levi and Stella Kramrisch. In fact, the credit for introducing Tagore to the West goes to a Jew, Sir William Rothenstein, to whom Tagore dedicated his collection of poems, Gitanjali: “He had the vision to see the truth and the heart to love it.”

Rothenstein even promoted Tagore and arranged for a book reading before an audience that included poets like Ezra Pound, and even made William Butler Yeats to write the introduction to the English translation. Sir William Rothenstein vigorously promoted Indian art and literature and strongly supported the Bengal School of art, in his capacity as the principal of the Royal College of Art, London, from 1920 to 1935. Rothenstein saw Tagore as “one of the most remarkable men of his time” with an “inner charm as well as great physical beauty.”

Stella Kramrisch was another Jewish artist Tagore came in close association with. She was invited by him to join Kala-Bhavan at Visva Bharati as a teacher of art history. Her experience working with Tagore is summed up in her own words: “Living in the nearness of Dr Tagore makes me realise India in full intensity.” In fact, the very first visiting professor at Visva Bharati was a Jew, Sylvain Levi, one of the greatest orientalists ever, who Tagore met during his visit to Paris in 1920-21 and immediately extended him the invitation to be a Visiting Professor at Visva-Bharati, which he readily accepted. Levi stayed there for a year, 1921-22, and taught French, Chinese and Tibetan languages. We get an idea of his experience there from what he wrote to Tagore I923: “I do not know if Santiniketan will ever rank among the most developed institutions of learning in the world, but you can be satisfied that you have built up an abode of unparallel peace. I long [for] the day when I can sit again in the shade of the mango-trees, walk along the noble alley of shals, talk, dream, listen to music, to verses, enjoy your delightful, sweet, dear company together with the beloved friends there.” Another Jew to teach at Visva-Bharati was Moriz Winternitz, professor of Indian philology and ethnology at German University, who was acknowledged as an authority on ancient and medieval Indian literature.

But of all the Jews Tagore made friends with, it was his friendship with Albert Einstein which made international news. It was his dialogue with him that came to be written about extensively. He met Albert Einstein a number of times; the first being during his second visit to Germany in 1926. But Einstein was certainly aware of Tagore by 1919 (or even earlier), for they had signed together an anti-war ‘Declaration of the Independence of Spirit’. No wonder Tel Aviv remembers Rabindranath even more than a century and a half after his birth.