Inclusiveness reflected in Festivals of Bengal

Her flowing black mane covers her nudity as she represents the Tantrik Shakti of the Universe. But have you ever wondered who crafts those curly hair of Goddess Kali? Parbatipur is a small village around 40 km away from the city centre of Howrah. It is here that around 60-70 Muslim families for generations have been into the business of making Goddess Kali’s hair that adorns the various idols churned out from Kumartuli.

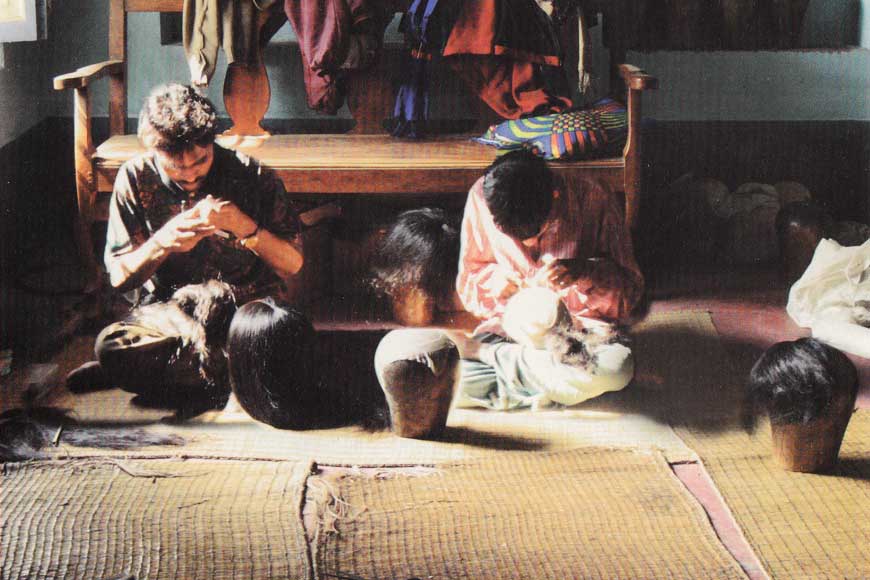

They have been doing this for decades, reflecting the inclusiveness of festivals of Bengal where people of different communities and religions have always participated together. However, this village came to the spotlight after a documentary called ‘Hairloom’ was made on the families. From the onset of autumn, the craftsmen of Parbatipur start collecting jute bales and every member from men, women, children participate in colouring the jute strands with black paint. They are done so professionally and with so much skill that they look like real human hair. They are done in bulk, supplying hair for almost 30,000 idols and make their way to the idol makers of Kumartuli.

Take for example Iftekar Hassan who is popularly known as Iftekar Chacha in Parbatipur who remembers how more than five decades ago this work of making idol hair started in the region. ‘Not just Kali, we do the hair of Durga idols too and all round the year most hair of idols of different goddesses come from Parbatipur. I did, my son’s family does and so even my grandsons.’

When asked how it feels to do this work, considering being a Muslim, he is working for a Hindu idol, Hassan laughed and said: ‘It gives us our bread and butter. And that’s more important than anything else to us.’ His son Jainal, who was also making the bales added that there were around a thousand people attached with this work. Due to COVID-19, number of idols have reduced, but they still got orders for hair making as all kinds of Durga and Kali idols, need hair. This village has already gained popularity for the superior quality of hair made by the villagers. They do not go looking for orders anymore as the organizers visit them, around four months prior to the festival, and list their requirements.

The jute bales usually come from local farmers. The bales are then dyed in black with the help of colors and chemicals. They are then suspended with bamboo logs and left to dry. It usually takes four to five days for the bales to dry completely, they are then removed and cut off into different sizes. Unfortunately, there are several health hazards attached to this job. Constant exposure of women and children, who primarily do the chemical colouring part cause breathing ailments as the colours give off poisonous gases. The women and children usually earn around Rs 300 a day depending on the number of bales they can colour and cut.

Interestingly, Parbatipur also has Hindu idol makers like Nabakrishna Pal, who buy the hair from his ‘Muslim brothers.’ Pal has been in this village for more than 40 years and never for once felt the tug of religion while making idols and buying the shiny hair for them from Muslims. He smiles and adds: ‘Even the Goddesses give us the message of unity. Why should we destroy the unity? We have been living together for generations and while doing business not even for once we felt who belongs to which community.’

No wonder, the Goddess Kali or Maa Durga has unified the village for decades and so has the need for the shiny flowing mane of Goddess Kali. The darkness of the Amavasya night could never impact the evils of communalism in Parbatipur. Rather it acted as a bond that comes down generations.