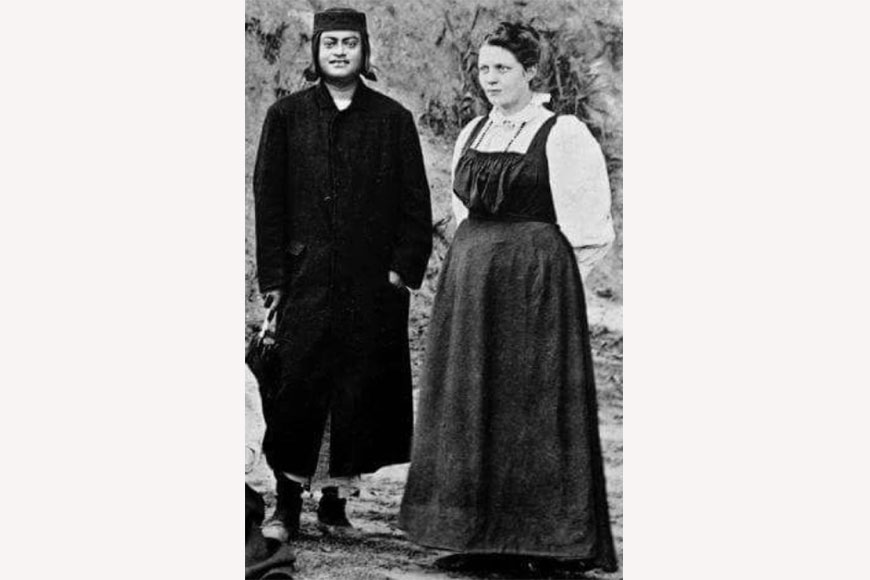

‘I shall not live to be 40 years old’—How did Swami Vivekananda know when he would die?

Swami Vivekananda attained Maha-Samadhi on July 4, 1902, at the age of 39. By then he had lived life on his own terms and was ready for death. Vivekananda’s death was not an episode, it was almost a journey and the manner in which he approached it, is intensely symbolic of the calm composure and the mastery of the fear of the unknown. He embraced death free of any fear or apprehension. How did Swamiji view Death?

Swami Vivekananda advocated Advaita Vedanta that holds all men as one in spiritual brotherhood, but that the last word in religion is man’s realization of his essential oneness with the entire universe. The central teaching of the Vedanta - the Upanishads - is how to realize this oneness. He propagated his views on death time and again, in his writings and his lectures. Death is not something to be fearful of or kept at bay, rather it should be embraced and accepted like all other worldly undertakings and he showed the way to do it. He always predicted that he would not live beyond the age of 40 and when he breathed his last, he was just 39 years and five months old.

In March 1900, Swamiji wrote a letter to Sister Nivedita. There, he wrote, “I don’t want to work. I want to be quiet, and rest. I know the time and the place; but the fate, or Karma, I think, drives me on – work, work.”

When he said, “I know the time and the place,” he was obviously referring to the time and place of his demise. It was, after all, just over two years after writing that letter that Vivekanda died, on July 4, 1902, preceded by detailed study of the almanac in the preceding days, the specific pointing out of the spot of his cremation three days before his demise, and instructions to brother-disciples on the future of the Ramakrishna Math on the day itself. Earlier in that year, Romain Rolland has noted that Vivekananda began to decline to express his opinion on the questions of the day with the response, “I can no more enter into outside affairs; I am already on the way.” The man who had said “I shall not live to be 40 years old” and moved on at 39 was clearly no stranger to his physical end and approached it with a sense of anticipation, if not familiarity.

His belief is reiterated in a letter he wrote earlier to one of his disciples, Mrs Bull in 1895. Mrs. Bull lost her father and was heart-broken. When Swamiji received the news, he wrote her a very gentle letter, comforting her in his own inimitable way. His letter is one of the most profound views on the mystery of death. He wrote, “Coming and going is all pure delusion. The soul never comes nor goes. Where is the place to which it shall go, when all space is in the soul? When shall be the time for entering and departing, when all time is in the soul?

The earth moves, causing the illusion of the movement of the sun; but the sun does not move. So Prakriti, or Maya, or Nature, is moving, changing, unfolding veil after veil, turning over leaf after leaf of this grand book- while the witnessing soul drinks in knowledge, unmoved, unchanged. All souls that ever have been, are, or shall be, are all in the present tense…Because the idea of space does not occur in the soul, therefore all that were ours, are ours, and will be ours, are always with us. We are in them. They are in us…

…The whole secret is, then, that your father has given up the old garment he was wearing and is standing where he was through all eternity. Will he manifest another such garment in this or any other world? I sincerely pray that he may not, until he does so in full consciousness. I pray that none may be dragged any whither by the unseen power of his own past actions. I pray that all may be free, that is to say, may know that they are free. And if they are to dream again, let us pray that their dreams be all of peace and bliss…’

On March 7, 1900, Swamiji delivered a lecture in Oakland on the subject, ‘The Laws of Life and Death.’ The Swami said: ‘How to get rid of this birth and death — not how to go to heaven, but how one can stop going to heaven — this is the object of the search of the Hindu.’

Swamiji went on to say that nothing stands isolated — everything is a part of the never-ending procession of cause and effect. If there are higher beings than man, they also must obey the laws. Life can only spring from life, thought from thought, matter from matter. A universe cannot be created out of matter. It has existed for ever. If human beings came into the world fresh from the hands of nature, they would come without impressions; but we do not come in that way, which shows that we are not created afresh. If human souls are created out of nothing, what is to prevent them from going back into nothing? If we are to live all the time in the future, we must have lived all the time in the past.

It is the belief of the Hindu that the soul is neither mind nor body. What is it which remains stable — which can say, ‘I am I? Not the body, for it is always changing; and not the mind, which changes more rapidly than the body, which never has the same thoughts for even a few minutes.’ There must be an identity which does not change — something which is to man what the banks are to the river — the banks which do not change and without whose immobility we would not be conscious of the constantly moving stream. Behind the body, behind the mind, there must be something, viz the soul, which unifies the man. Mind is merely the fine instrument through which the soul — the master — acts on the body. In India we say a man has given up his body, while you say, a man gives up his ghost. The Hindus believe that a man is a soul and has a body, while Western people believe he is a body and possesses a soul.

Death overtakes everything which is complex. The soul is a single element, not composed of anything else, and therefore it cannot die. By its very nature the soul must be immortal. Body, mind, and soul turn upon the wheel of law — none can escape. No more can we transcend the law than can the stars, than can the sun — it is all a universe of law. The law of Karma is that every action must be followed sooner or later by an effect. The Egyptian seed which was taken from the hand of a mummy after 5000 years and sprang into life when planted is the type of the never-ending influence of human acts. Action can never die without producing action. Now, if our acts can only produce their appropriate effects on this plane of existence, it follows that we must all come back to round out the circle of causes and effects. This is the doctrine of reincarnation. We are the slaves of law, the slaves of conduct, the slaves of thirst, the slaves of desire, the slaves of a thousand things. Only by escaping from life can we escape from slavery to freedom. God is the only one who is free. God and freedom are one and the same.

It is amazing to think how evolved a mind had to be to have a sense of when time here is going to run out, and to go on with a sense of energy, the drive that Swami Vivekananda displayed during his temporal existence and made it worthwhile.

Source: Letters and Lectures of Swami Vivekananda On Advaita Vedanta