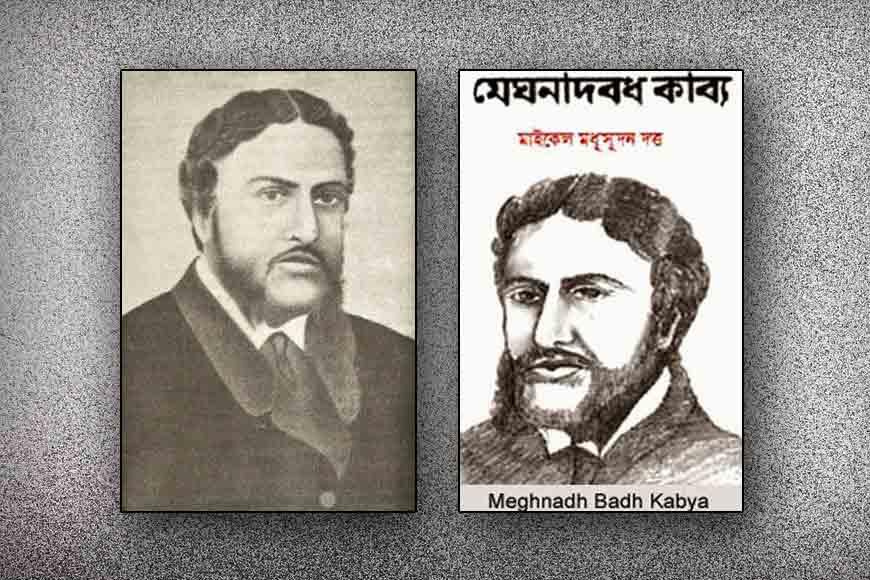

How Madhusudan Dutta defied Ram and made Meghnad the hero

When I first read a major excerpt from Meghnadbadh Kabya as part of my board examination syllabus, I felt like re-reading again. Not because Michael Madhusudan Dutta had used international poetic tools in an age when Bengali poetry could least imagine such treatment, but because of the boldness in choosing his hero. He was not Ram, not Lakshman, but Meghnad, son of Ravana, who we burn on the Ramleela grounds every year, relating him to evil. I could immediately relate to the righteousness of Meghnad, fighting a tragic hero’s ground and dying due to the manipulation of war rules by none other than Ram and his brother Lakshman, who almost the whole of India pray as God. But isn’t it said in war and in love everything is accepted and everything is possible. The ever honourable king Ramchandra has thus been exempted from the manipulation he did in the war rules, while killing Meghnad. Shall we then say neither of the brothers had the guts to take on the valiant Meghnad face to face as they knew he is a greater warrior than them?

Madhusudan Dutta’s Meghnadbadh Kabya, one of the most celebrated of his works, was brought out in 1861. Well, that is almost one and a half century ago. It is a landmark in the history of Bengali literature with its rich repertory of Bengali blank verse, a style that was unknown to the readers. As one of the pioneers of Bengali poetry and influenced by European epics, Madhusudan Dutta’s genius made way through the epic poem Meghnadbad Kabya. It is a tragedy, divided in nine cantos, and follows the renaissance tradition of challenging the myth. Madhusudan Dutta questions the justification of killing an unarmed Meghnad as he is worshipping in the temple. It is almost similar to another epic tale of world literature, Milton’s Paradise Lost or even Goethe’s Faust that make us sympathetic towards the ‘rebel’ or the ‘villain.’ Madhusudan’s sympathy was also with Meghnad, a sharp break from the Hindu tradition of worshipping Ram and Lakshman and turning Ravana and Meghnad into evil faces.

Slaying of Meghnad was undoubtedly done like a coward, when Lakshman storms into the temple where Meghnad worships unarmed and kills him. The way Meghnad reacts to such a celebrated warrior’s misgivings, flouting norms of the warfare, find a new dimension through Madhusudan Dutta’s new rhyming pattern and the pathos of a death reflects the deepest anguish of a character who we so easily burn every year at the stake, just because he is not Ram. But have we ever had the guts to question why some characters of Hindu mythology like Ram who have always shown signs of patriarchy and manipulation, have been worshipped? And why characters like Ravana, who reflects utmost restrain in not touching Sita while under his captivity or even Meghnad, who was probably a greater warrior and had more valour than even Ram or Lakshman burnt and branded as evil? Probably we shall never be able to question just like Madhusudan Dutta could more than a century ago. Thankfully, he didn’t live in present time, else just like the Dutch artist who drew cartoon of Prophet Mohammed and was hounded with a death warrant, may be Dutta too would have been banned by the Hindutva brigade today.