How did Calcutta ring in the New Year, 200 years ago? - GetBengal story

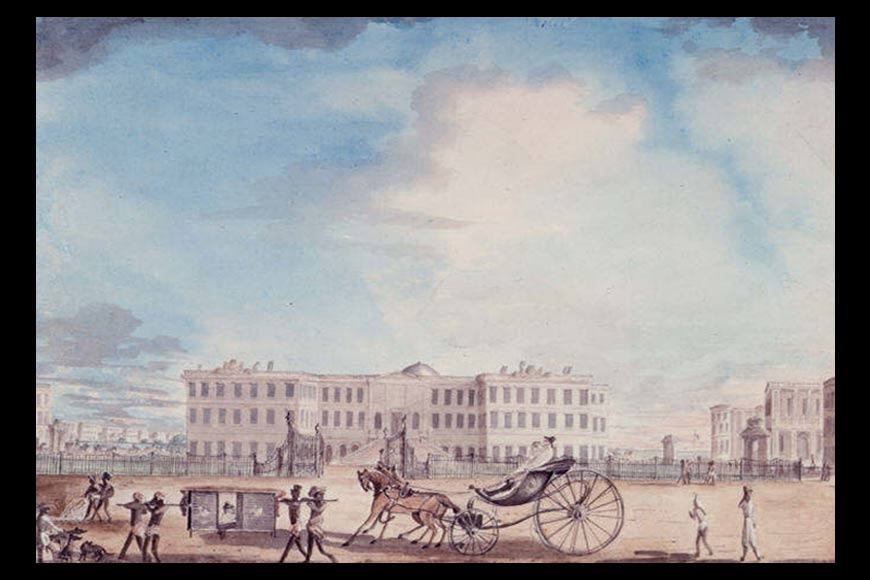

The Government House in the 19th century, an artist's impression

What was a New Year’s party like in Calcutta of the 18th century? As 2025 dawns upon us, we thought it might be fun to travel back in time and look at what was a quintessentially British import, the Christmas and New Year week. Given the thriving European population in Calcutta by the middle of the 18th century, these festivities had become such an integral part of the city’s social calendar that it seemed as though they had been there forever.

Sir Philip Francis (1740-1818) was a British politician and pamphleteer, but he has gone down in British-Indian history as the man who brought accusations of corruption against Bengal’s first Governor-General Warren Hastings, and even fought a duel with him on the road still called Duel Avenue in Kolkata’s Alipore. It was his stance against the Governor-General that led to the joint impeachment of both Hastings and Elijah Impey by the British Parliament. But this digression is merely intended to set some context. We’re actually interested in Francis’ brother-in-law Alexander Mackrabie, whose writings during his brief lifetime give us an excellent picture of Calcutta’s end-of-year party scene.

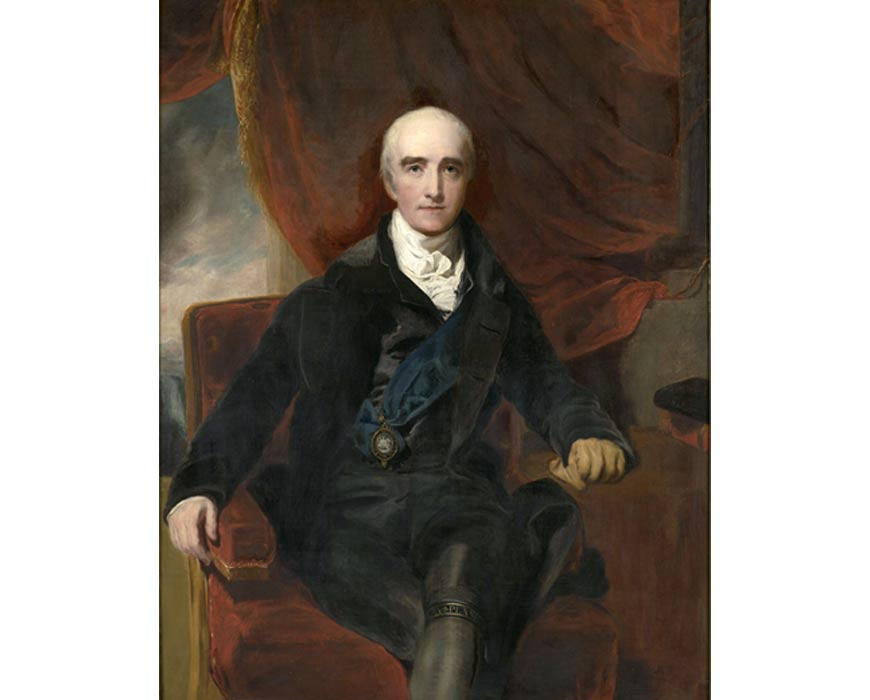

Governor-General Wellesley

Governor-General Wellesley

As sheriff of Calcutta in the 1770s, Mackrabie was in a position to attend some of the city’s most notable events, and has left behind invaluable memoirs describing them, including New Year parties hosted by the Governor-General. At a time when it was not unheard of for affluent European households, even small ones, to keep more than 100 servants, it may be imagined that a party at the Governor-General’s residence would be a truly lavish affair, given the abundance of human resources.

Nonetheless, describing the first Christmas Day celebrations he attended after his arrival in India in 1774, Mackrabie wrote, “It is the most absurd of all possible ceremonies.” Apparently, Hastings hosted a public breakfast, dinner, ball, and supper (the British name for the last meal of the day), and “every Member of the Council, the Judges, the Board of Trade, Field Officers, Clergy, and Heads of Offices are pestered with the repetition of a ‘Merry Xmas’ etc,” according to Mackrabie.

New Year’s Day was pretty much treated as an extension of Christmas, and cannons were set off to announce a series of toasts to prominent officials who had displayed outstanding loyalty to both the British East India Company and the Governor-General. A typical party began at around two in the afternoon on New Year’s Day itself, and went on into the early hours of the next morning.

Also read : Slavery, the dark secret from Calcutta’s past

The parties were customarily held either at Old Court House or at the Theatre, since Government House was not deemed large enough. Writing in 1790, the French traveller Grandpré rather dismissively observed, “He lives in a house on the esplanade, opposite the citadel - many private individuals in the town have houses as good. The house of the Governor of Pondicherry is much more magnificent.”

View from the South Gate of Raj Bhavan today

View from the South Gate of Raj Bhavan today

In fact, it was not until the time of Lord Wellesley (1796-1805) that the Governor-General acquired a residence worthy enough to accommodate guests. And it was in January of 1803 that the New Year was heralded with a spectacular display of sound and lights, with a guest list of 800 people! Among those present was one Lord Valentia, who later wrote, “A small, quiet party seems unknown in Calcutta…”

On that note, here’s hoping the new year is better than the last, and brings hope and happiness in equal measure.