How America deals with PNPC…or not!

A long, hard journey later, exhausted and battle-weary, we came to New York to stay. Finally, we could talk about our terrible, dark times with a few American friends and well-wishers. When they had become pointless to talk about. Those we spoke to were the ones nearest to us, not related by blood, but who had grown closer than family in the time we had spent in this country.

Without exception, they all told us we had fallen victim to the tremendous racism and injustice of America. Had we been White, or rich, the White American Dr Daniel Nord would never have neglected my wife during her childbirth. And all of them also said that our friends at the time, and the Illinois State University authorities, ought to have arranged financial compensation for the terrible damage done to us.

I will not even mention the emotional agony and trauma. Just suffice it to say that my wife suffered permanent physical impairment following that catastrophe.

We don’t usually talk about personal issues with any and everybody. Our indigenous value systems and social norms teach us to be discreet. Besides, we cannot easily trust anyone, because many of us are not taught the importance of keeping other people’s secrets. Talk about your true feelings or problems with anyone, and the next thing you know, they and their friends are circulating your story like a recurring decimal. Or like potato chips. And they fall silent as soon as they see you. There’s no way of cornering the person you first told your story to. Neither do you wish to, perhaps.

We are too decent, really. We lack the honest courage to protest injustice. Why invite trouble? Instead, we move away from the discussion for the sake of self-respect. What we call PNPC (poro ninda poro chorcha, the Bengali version of juicy, malicious gossip) then grows roots and settles down. Stories become sagas, sagas spawn rumours, rumours give birth to scandal.

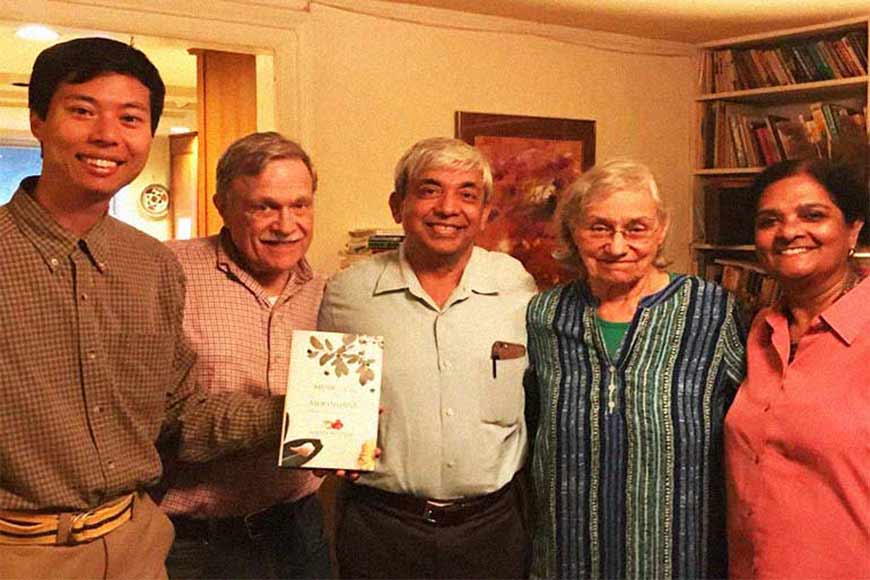

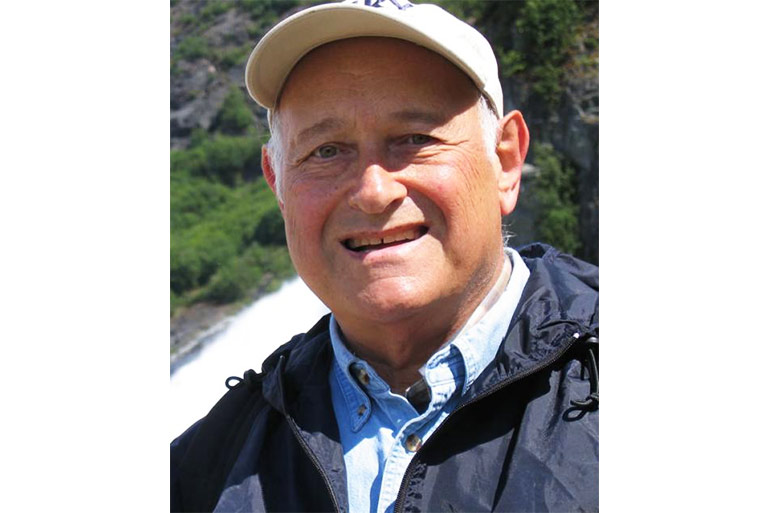

And yet, you can be 100 percent sure that you can safely reveal your innermost thoughts to an American friend, because the matter will end there. Nobody else will hear that story. Which is why we could talk to the doctor couple Charlotte Philips and Oliver Fine. Or my PhD research professors Walt Sandberg and Larry Matten. And the Bengali couple Tanushree and Prabhat. They never broke our trust.

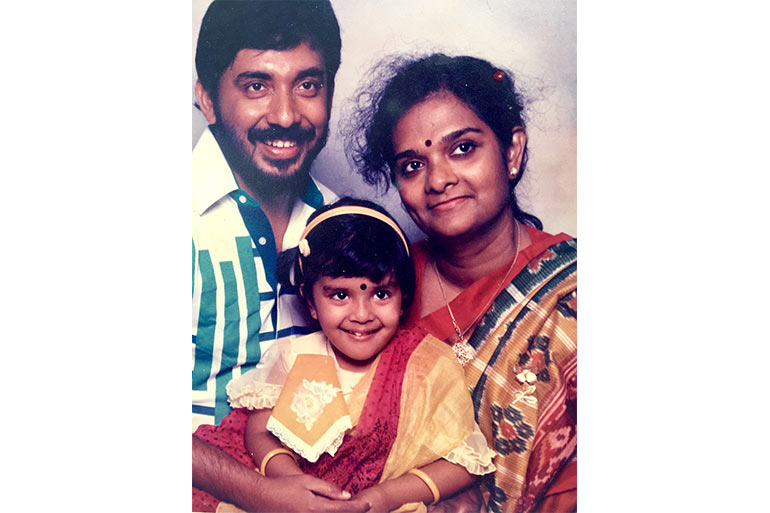

Neither Tanushree nor Prabhat grew up in Kolkata. They had no ties to the city’s pseudo-intellectual class, no ties to Salt Lake, Ballygunge, Fern Road, Beltala, or New Town. Which is perhaps why they were marginalised by New York’s westernised Bengali community. Exactly what happened to Biswada and Rebecca boudi in Chicago. The couple who saved me from complete extinction during those early days in America.

Tanushree and Prabhat are working class. They drive an old blue Buick, live in an old single-storey house. They can’t sing Rabindra Sangeet, and Uncle Bob’s friends are mostly Gujarati, who nose-in-the-air Bengalis call Gujjus. They lack pedigree. Whipped and ravaged by reality, the Nath family have not really cemented any ties with the Bengalis of the West.

No one has kept track of how many wealthy ‘Bong’ lives Tanushree and Prabhat have saved in Albany city. Tanushree is a registered nurse, Prabhat a biologist. But theirs is a story for another day.

There’s another side to this. Over the years of living in America, I have realised that American friends, no matter how brief the acquaintance, tend to share all kinds of personal information. Stories of abuse by a husband or boyfriend, for instance. Or a lady talking about how her father had been married for a third time, to a woman 20 or 25 years younger. And how the woman had left him for a former lover because he was unable to lead a proper married life.

“You see (in a low voice), this woman married him for his money. They had no chemistry between them. (Pause) You know what I mean? (assuming I hadn’t got it) Like, my dad was old by that time. They had no sex life (sad smile).”

This is America. Call it good or bad. Feel free to feel disgusted. Because it doesn’t fit the old-time value system of our generation at all. Such talk amazes us, makes us really uncomfortable. We keep wishing the discussion would end. Back home, we make a joke out of it for the family. Our conversations about it drift aimlessly into the horizon, like a kite with a snapped string.

And yet, who knows how many millions of marriages in our country die like this? No matter how unhappy they are, they can’t leave. Our society hasn’t given women the financial freedom or the mindspace to do so. They have nowhere to go.

_________

Our own extended families indulged in plenty of PNPC about our move to America. We heard about it much later, but here’s a brief, imagined summary of what some of our close relatives decided must have happened once we left.

“How did Partha get to America?”

“Partha who?”

“Oh come on, Mukti’s Partha, her husband.”

“Oh that Partha? Partha Banerjee? He’s in America?”

“You mean you don’t know? It’s been almost a year now.”

“I do remember someone saying so. Partha was in that Sundarban…”

“I know, that is exactly what I’m saying. He couldn’t even find a job in Kolkata. Of course, not a first class in MSc!”

“Didn’t even get a first class?”

“Pshaw, such an ordinary student! Finally used CPIM connections to go to that Sundarban college…”

“Mukti got a job in a Kolkata college though, didn’t she?”

“Oh but she was a brilliant student. Went to Presidency College. Partha only went to Vidyasagar.”

“But then how did he make it? Damn, everyone’s going to America these days. I want to go too.”

(Loud laughter from the group)

“(First speaker) But actually, you guys don’t know the real story. Partha’s dad is some RSS big shot. He’s friends with Atal Behari Vajpayee. I’ve heard his dad literally went to Vajpayee. That’s how the chance came.”

“(The others) No! Really?”

“(Second speaker) Could just as well have been Jyoti Babu. Mukti’s dad is in the CPIM. Maybe they went to Jyoti Babu to get him out of that village college.”

“(The others? Really? What are you saying?”

These conversations, the PNPC, lovingly nurtured in secret, came to our ears after nearly 25 years in America. By chance.

(To be continued)

Translated from Bengali by: Yajnaseni Chakraborty

We are happy to present ‘Mericamaya Satkahan’, a weekly column by renowned human rights activist Dr Partha Bandyopadhyay, every Monday on GetBengal