His passing has orphaned us

Of all the residents of Dhaka, 99 percent are from various corners, districts, villages, and towns of Bangladesh. On the first meeting, the commonest question is, ‘So where do you come from originally?’ I’ve heard elderly people in Kolkata say the same thing about the time immediately following Partition. Among the large refugee population in Kolkata and its outskirts, across districts, the question then was, whereabouts in East Bengal are you from?

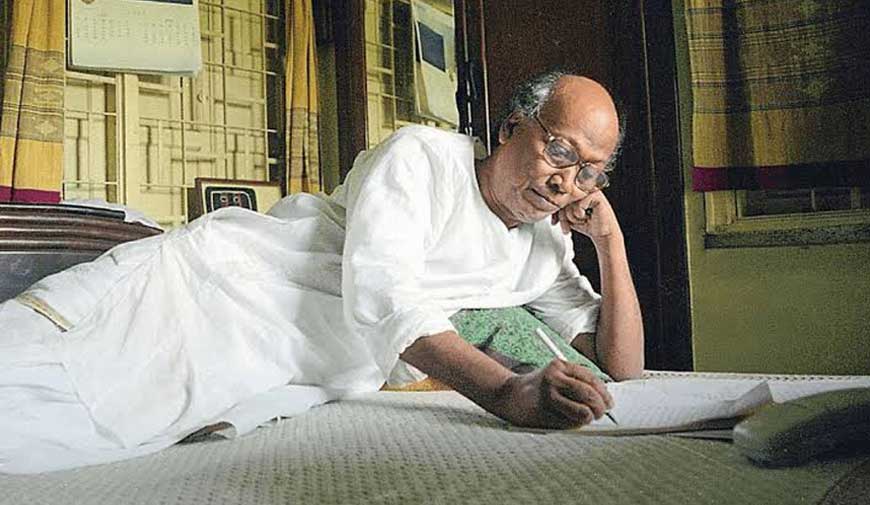

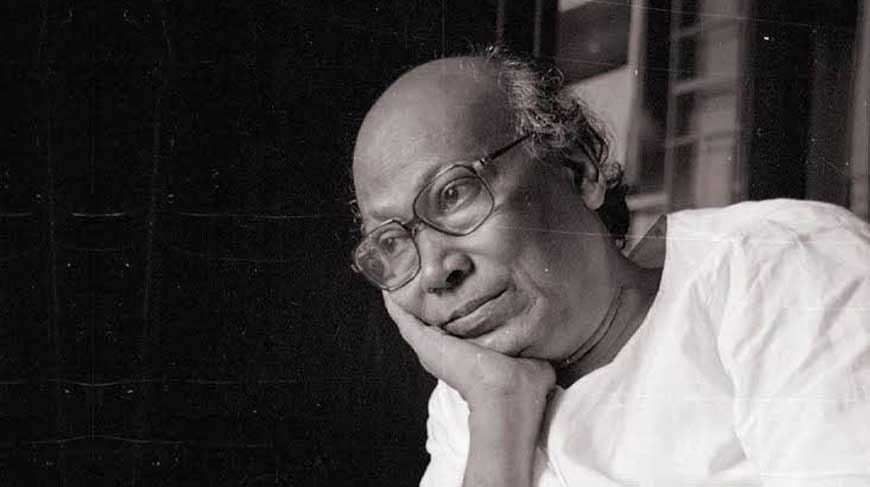

Shankha Ghosh did not have to answer this question, the answer is scattered throughout his writings, his prose, his memoirs. He never wrote down his life story, but his readers knew much of it from his published works anyway.

Born in East Bengal, Bangladesh today, he was an Indian citizen. Having arrived in Kolkata as a refugee, he lived here until the day he died. But his heart and soul belonged to Bangladesh. His many writings on Bangladesh bear testimony to that fact. Those writings have been published from Dhaka in multiple volumes. As have his poems about Bangladesh.

After Bangabandhu’s assassination on August 15, 1975, he came up with a truly lovely eight-line tribute, titled ‘Dhaka 1975’.

সমস্ত ধুলোর মধ্যে মিশে থাকে স্তব

তোমার পায়ের মুদ্রা থেমে থেমে যাবে

প্রতিটি সকাল থেকে ভ্রমণের স্মৃতি

চোখের প্রথম মুক্তি নদীতে তাকাবে

কৃষ্ণচূড়া এ শহর করে দিক রাধা

তখনই সবার বুকে দামামা বাজাবে

ছিন্ন মুহূর্তের সেই ভস্ম হওয়া জ্বালা

সেদিন আমার ছিলে, আজ কার পালা?

(Rough translation: There’s adulation in every grain of dust

The pattern of your feet will come to a halt

The memories of morning travels

The unfettered eye will gaze at the river

Let the Krishnachura turn this city into Radha

Every chest will feel the drumbeat

The searing agony of that torn moment

You were mine that day, whose are you today?)

His memories often illuminated his writings. Such as the 18-line quasi-rhyme titled ‘Amar Paksey’. Almost a children’s poem, really, but masking a deep attachment to his village, which he never forgot:

যতই হাসো, যাই বলো লিখে তো রাখছি

দুনিয়ার যে সেরা শহর - সে হলো পাকশী।

অবশ্য ঠিক শহরও নয়, শহর-মেশা গ্রাম

গ্রাম-শহরের সেই দোটানায় প্রণতি রাখলাম

………………………………………………

সে আজ আমায় ডাক দিয়েছে আদ্যিকালের থেকে

চলো আমরা সেইখানে যাই এখনই প্রত্যেকে

তোমার গ্রামকে তুচ্ছ করছি? তুলনা থাক, ছি!

সবার দেশই সবার ভালো, আমারটা পাকশী।

(Rough translation: ‘You may laugh, say what you want, but mark my word

The city of Paksey, it’s the best in the world

Not all city, not all village, more a mix of the two

There’s a dilemma, but my homage remains true

……………………………………………………...

I have heard the call come to me from an age long gone

Let’s all go there, this minute, each and every one

You say I ignore your village? How can you compare!

To each their own country, mine is Paksey fair)

Chandraprabha Vidyapith-Paksey

Chandraprabha Vidyapith-Paksey

Paksey is barely 15 miles from Ishwardi in Pabna. The river Padma flows close by, with its famous Hardinge Bridge. The other landmark is a school set up in 1924, Chandraprabha Vidyapith, later renamed the Bangladesh Railway Government Chandraprabha Vidyapith. This was the school from which Shankha Ghosh completed his matriculation. His father Manindra Kumar Ghosh, a famed Bengali language scholar, was also headmaster of the school. A true man of letters, he was well acquainted with Rabindranath Tagore and enjoyed regular correspondence with him.

Also read : Shankha Ghosh, the quiet revolutionary

In the late 1970s, Shankha Ghosh obeyed an inner call to go and revisit his old school. The teachers were overwhelmed with delight, and the students wouldn’t let him go until he had written something for them. Thus was born ‘Amar Paksey’, an outpouring of his innermost thoughts.

In later life, too, his students were more like his own children, his love and affection forever pure. Even today, it amazes me to recall one occasion when he took his students from Jadavpur University’s Bengali department to Indira theatre to watch ‘Ami Shey O Sokha’. I was there, too, but in a back row where he didn’t see me. As we emerged from the theatre at the end of the film, he saw me and simply asked, ‘Did you like it?’

I was a student of Comparative Literature, and one of our prescribed texts was Tagore’s ‘Pother Sanchay’, for which Shankha Ghosh would take a 45-minute class every Saturday. For three months, I attended the special class, and watched and listened as he patiently answered all our questions in great detail.

Shankha Ghosh was the voice of our conscience, in every way, as our collective conscience grows progressively weaker. His passing has orphaned us. We are now without a guardian.