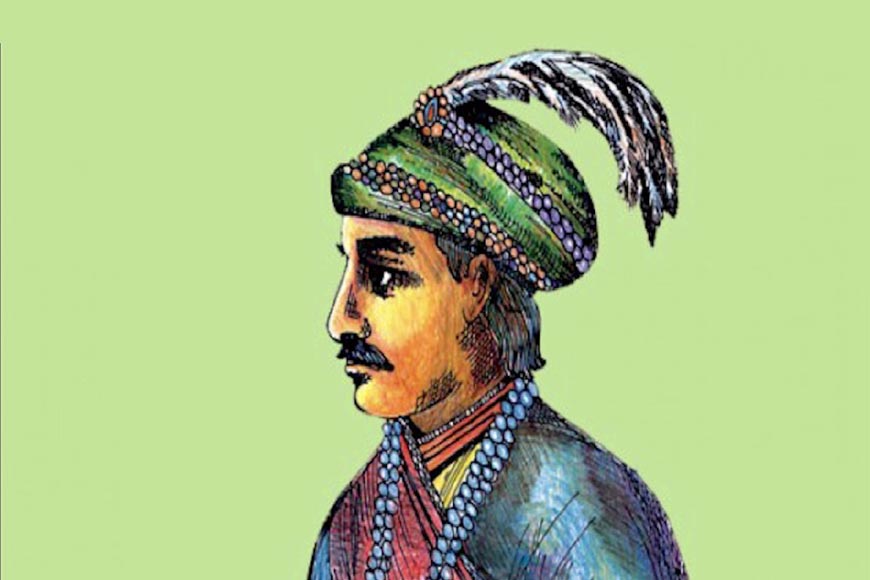

Hindu son of Siraj-ud-daullah: Jugalkishore, the dashing feudal lord

Part 2: Jugalkishore, the dashing feudal lord of Bengal who did not look like a Bengali

Jugalkishore, the young, dashing feudal lord of Mymensingha was growing up into a fine young man under his uncle Krishnakishore’s tutelage and supervision. He was a remarkably intelligent boy who soon became proficient in running the administration of the estate. The Chowdhury family traditionally celebrated the annual ‘Ratha-yatra’ (Chariot festival) with much pomp and splendor. Their subjects waited with much anticipation for the annual ritual. However, in 1764, a disaster thwarted the celebration permanently. Krishnakishore and a few of the landlord’s servants died in a tragic accident during the chariot festival and since then, the family festival was halted permanently.

Jugalkishore succeeded his deceased uncle and became the Zamindar. He shouldered the full responsibility of looking after his uncle’s widows, Ratnamala and Narayani but later their relationship deteriorated following property disputes which resulted in long-drawn legal battles between Jugalkishore and his aunts that went on for decades. It is believed that Krishnakishore’s widows came to know about Jugalkishore’s bloodline and wanted to sever all relationships with a ‘Muslim’ boy and deprive him of his feudal rights. They threatened to reveal his actual identity to British officials and Mir Jafar’s spies.

Jugalkishore was intelligent, tall, handsome, powerful, skilled and a benevolent landlord. His physical attributes were starkly different from Bengalis and he stood out for his sharp features and fair skin. He knew his life would be endangered if his aunts spoke against him or revealed his identity. So, he decided to call for truce and convinced them to accept a handsome pension and in lieu give their written consent to acknowledge Jugalkishore as the sole heir of the entire estate. However, that eventually did not happen and he got embroiled in legal battle against his aunts. He was a very efficient administrator and he expanded his Zamindari considerably. In the process he also got entangled in several cases relating to property disputes, conflicts with another zamindar and even faced police action.

In the initial years of his rule, Jugalkishore was inclined to spiritualism and met the famous yogi Pandit Mohan Mishra at Pakuriya village in Rajshahi. He was baptized by Mishra and Jugalkishore practiced Kali/ Shakti sadhana under his guru’s guidance. Later, he set up a Kali temple and 12 Shiva-lingas at Bokainagar, another Kali temple at Netrakona and a Radha-Mohan idol at his zamindari in Jafarshahi, Mymensingha. He looked after his subjects well and concentrated on developmental projects for their welfare, including road construction and digging wells and ponds in his estate at Gouripur and other parts of his zamindari. He also established a village named Jugalkunj in Jafarshahi.

Jugalkishore was very efficient and could take quick decisions – a trait that endeared him to his subjects. Once Mymensingha was swept by heavy floods leading to acute scarcity of food. People lost their homes and their meager belongings. This led to wide-scale anarchy in the zamindari. Looting was rampant and the condition of ordinary people was miserable. Jugalkishore firmly handled the situation to restore peace and normalcy in the zamindari. This was also the time when the Sannyasi Rebellion was rising in Bengal and Jugalkishore’s zamindari was also affected by the rebellion.

The Sannyasi Rebellion or Sannyasian revolt were led by sannyasis and fakirs (Hindu and Muslim ascetics, respectively) in Bengal, in the late 18th century which raised its head around Murshidabad and Baikunthupur forests of Jalpaiguri and then spread to other parts of Bengal. Historians have not only debated what events constitute the rebellion but have also varied on the significance of the rebellion in Indian history. While some refer to it as an early war for India's Independence from foreign rule, since the right to collect tax had been given to the British East India Company after the Battle of Buxar in 1764, others categorize it as acts of violent banditry following the depopulation of the province in the Bengal famine of 1770.

For hundreds of years monks had been visiting pilgrim sites. They used to take alms from zamindars but after the British imposed stiff taxes on zamindars, it became tough for them to give alms to ascetics. When officials of the East India Company confronted the volatile situation, they promptly branded the monks as looters and thugs and in 1771, 150 saints were put to death, apparently for no reason. This caused a major backlash leading to widespread violence. Most of the clashes were recorded in the years following the famine but they continued, albeit with a lesser frequency, up until 1802. Jugalkishore handled the rebellion with deftness but a series of natural disasters and high rates of taxes imposed by the British impacted his financial status considerably. With his sharp acumen and foresight, Jugalkishore restored peace within his zamindari and with proper revenue management successfully attained financial stability over a period of time.

Again, Jafarsahi was once swept by a pandemic and many people died. Jugalkishore was very anxious to find a solution but when nothing seemed to constrain the spread of disease and deaths, he decided to shift his zamindari to Gouripur with his family and subjects. Gouripur at that time was a sprawling tract of dense jungle but under Jugalkishore’s able leadership, Gauripur flourished.

(To be continued)

(Source: Professor Dr Amalendu De, legendary historian and former President of Asiatic Society and Indian History Congress. Dr De is considered an authority on history of pre-Independent India with many books to his credit. After 50 years of careful and meticulous research, Professor De not only found out Siraj’s descendants — many of whom are still living and part of well-known families -- but also gave details and chronology as to how the last Nawab’s bloodline followed till date in his book, ‘Sirajer ‘Putro-O-Bangshadharder Sandhane’)