Hemanta Sengupta: The man who became Gandhi’s bodyguard

Calcutta, January 30, 1948. Minutes before a Calcutta Police investiture ceremony is about to begin at Kalika Hall on Hazra Road. A senior officer is in attendance with his young son, who is growing impatient as the minutes stretch well beyond the scheduled start of the programme, the curtains still firmly drawn. All of a sudden, someone announces that Mahatma Gandhi, the Father of the Nation, is no more. Without wasting a minute, the boy’s father dashes to Bhawanipur police station, acutely aware of the riot-causing potential of what they have just heard. As he frantically calls police stations across the city to make sure that forces are deployed on the streets in adequate numbers, he has all but forgotten his son, who is watching and memorising every detail of this unforgettable event.

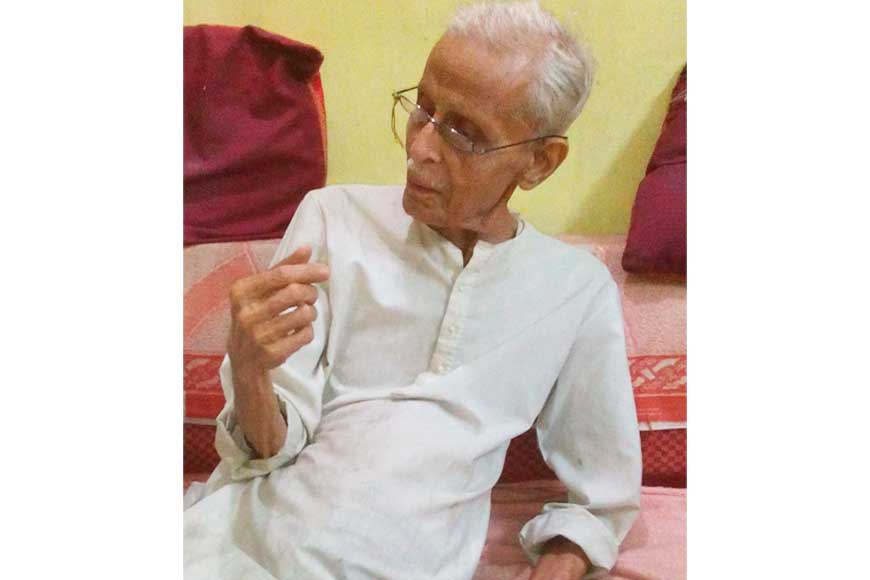

The boy is Chandi Sengupta, who had earlier had a chance to observe ‘Bapu’ closely in 1947 in the building now known as Beleghata Gandhi Bhaban. And so, on the terrible day of January 30 next year, images from the earlier occasion are still fresh in his mind. His father Hemanta Sengupta, originally from Jessore, was an assistant commissioner of Calcutta Police, and one of Bapu’s constant companions - Gandhi’s first Bengali bodyguard in independent India. The 12-year-old Chandi therefore had ample access to the Gandhi camp. During the 25 days from August 13 to September 7, 1947, Chandi’s father was in charge of Gandhi’s security arrangements in Calcutta. From Hydari Manzil to prayer meetings, Sengupta shadowed Bapu at all times, in the lead up to Independence and beyond it.

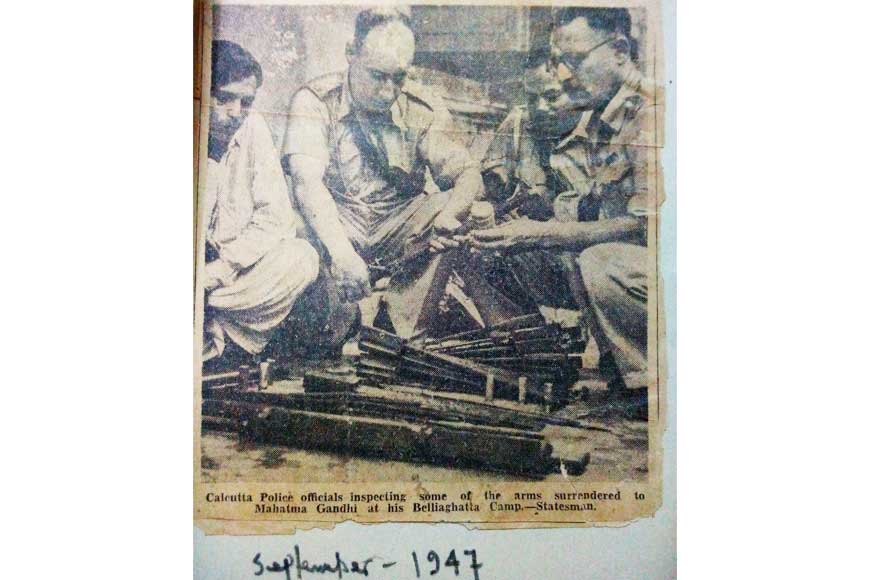

The wounds of the riots of 1946 were still open and raw, when 1947 brought with it a fresh wave of communal tension in Calcutta. On August 13, Gandhi arrived at Hydari Manzil in Beleghata, on what was clearly a political visit. A bodyguard was therefore of vital importance. Sengupta’s Jeep, bearing the license plate CP 37, would remain stationed outside the building, and head Gandhi’s convoy whenever he stepped out. Standing on the hoodless vehicle, it was Sengupta’s job to make sure that the thousands who lined Bapu’s route to catch a glimpse of him did not block his way. Waving the crowds away from the convoy, he would bellow orders in his deep, stentorian voice.

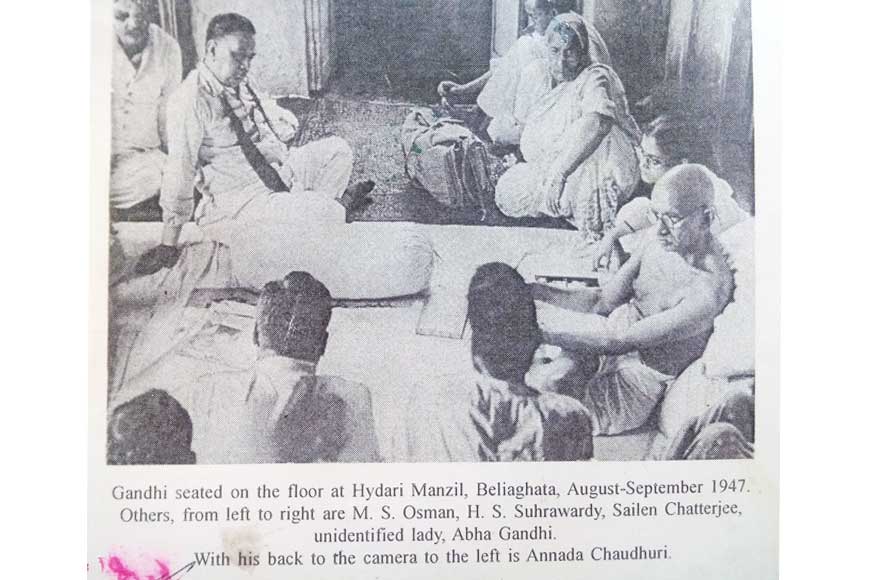

Back at Hydari Manzil, Chandi would often sit on a mat placed on the floor, quite close to Gandhi. That one room was the hub of all activity, so not all visitors could be accommodated. Many would stand at the windows, poking their heads in as far as they could. Inside, Gandhi would hold court in his short white dhoti, his back resting against a wall, his associates seated around him in a half-moon semicircle. Manu and Abha Gandhi were a constant presence, as was Bapu’s secretary, the renowned anthropologist Nirmal Kumar Bose. Yet another daily visitor was Dr Mehta, whose job was to regularly monitor the leader’s health.

Amidst all the hubbub, Chandi would gradually push his way forward to the front row. Did Gandhi ever speak to the youngster? No, that he did not, but would often catch his eye and smile gently. Proudly carrying a dodgy camera, Chandi would take photographs of Bapu at various prayer meetings too. Nirmal Bose and many others, however, made it a point to regularly speak to the boy, often accompanied by affectionate gestures.

What was Mahatma Gandhi like as a person? Above all else, even a boy as young as Chandi realised how disciplined he was. Waking up in the very early hours of the day, he would finish his prayers before sunrise in the house itself. He would then step out of his room, pace around for a bit, and then sleep some more. When he awoke again, it was for a massage, bath, and breakfast. That done, he would make his way to the room at the left of Hydari Manzil, where work on the Harijan newspaper was also in progress.

As meetings and discussions progressed, Gandhi would simultaneously be working on content for Harijan, dictating notes to his associates. As the day grew, so did the crowds, among them bunches of autograph hunters. But only if they donated Rs 5 each to the Harijan fund would they be rewarded with an autograph. On a blank piece of paper, the Mahatma would simply write ‘Chiranjeev’, followed by the name of the autograph seeker. Chandi himself got one of these autographs too. Every day, visitors would bring fruits and sweets for Bapu, some of which would make their way to Chandi as they were handed around.

The prayer meetings were held at different venues every day. On some days, Suhrawardy would himself drive Gandhi to the meetings. Other wealthy citizens brought their cars too. Among the venues was the stretch of grass beneath the Shahid Minar on the Maidan, or the Mohammedan Sporting ground nearby, where large crowds braved pouring rains and ankle-deep mud to stand and listen to Bapu. The meetings also featured vocalists such as Bijonbala and Juthika Roy.

In the age of Google, selfies, and social media, memories count for little. Everything can now be recorded, photographed, captured. But Chandi had nothing to store his memories in but his childish, wonderstruck mind. Most of these he took with him as he departed this earth in November last year, at the age of 84. As the country observes yet another Gandhi Jayanti today, Chandi Sengupta will no longer take a trip down memory lane in his Ballygunge Garden home. But not all his memories have gone with him. Because they have now become history.

All photographs courtesy the writer