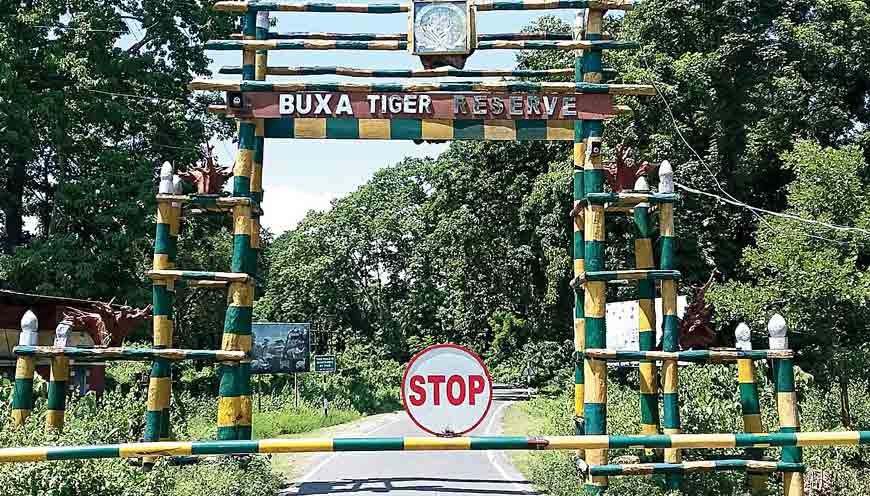

Has the Bengal Tiger truly returned to Buxa Tiger Reserve?

On July 29, 2019, India released the much-awaited and fairly delayed Tiger Census report 2018, which disclosed that the country had 2,967 Royal Bengal Tigers in the wild, though the census for the following four years is currently underway across various states, and the final report should be out on July 29, 2022 according to the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA).

In that context, the recent sighting of a lone tiger at Buxa Tiger Reserve in Alipurduar district has understandably excited wildlife activists and officials alike. Because the 2018 census had officially declared that there were no more tigers left in Buxa, the exact words being: “Tigers were not recorded from Buxa (West Bengal) and Dampa (Mizoram) Tiger Reserves which had poor tiger status in the earlier assessments as well.”

However, Nature Environment & Wildlife Society (NEWS) secretary and State Wildlife Board member Biswajit Roy Chowdhury says NEWS members found tiger droppings, technically known as ‘scat’, at Buxa during the last census. “Tiger scat can be DNA tested to find out whether it has indeed come from a tiger, and this was done at Buxa,” he says. “In my opinion, the tiger that has been spotted should be radio collared immediately. That way, we will know if it is a resident of Buxa Tiger Reserve not.”

For those wondering, a radio collar is a common method of tracking an animal’s movement and home range, population estimation, behaviour, habitat use, survival, and predator-prey interaction. The commonest radio collar is a wide belt fitted with a small radio transmitter and battery, whose signal can be tracked from up to a distance of 5 km. The possible reason Roy Chowdhury is advocating a radio collar for the Buxa tiger is the fact that Buxa may be a tiger reserve in name, but wildlife experts have consistently raised doubts about its suitability as a tiger habitat.

Roy Chowdhury has spent over four decades as a wildlife activist and photographer, but never spotted a tiger at Buxa. The pressure of human population in and around the reserve, as well as Buxa’s proximity to Phibsoo Wildlife Sanctuary in Bhutan and Neora Valley National Park in Kalimpong district has made it vulnerable to poaching, not just of tigers but priceless trees for wood, which causes habitat loss for deer, the tiger’s chief prey. That apart, very large herds of domestic cattle that graze the land around Buxa also survive on fodder which would otherwise have been consumed by deer. In the last two years, the tiger reserve has introduced at least 500 heads of deer in an attempt to lure tigers back, but whether the prey will breed in large enough numbers remains to be seen.

Traditionally a haven for numerous bird species, Buxa became a tiger reserve in 1983 and a wildlife sanctuary in 1986, and finally a national park in 1992. While it remains a highly suitable habitat and corridor for elephants and the Indian rhino, it causes a few problems for the Royal Bengal Tiger in terms of movement and corridors. Moving as they do in herds, elephants build their corridors through populated areas, but for a lone ranger like the tiger, a proper corridor through isolated forests is a far more difficult proposition.

Given all these challenges, and the intensive and diversified land use by humans around Buxa, a tiger sighting is naturally a matter for great excitement. Whether this is the beginning of many, only time will tell. Meanwhile, the reserve remains home to more than 70 other large mammal species such as the Asian elephant, gaur (Indian bison), Sambar deer, clouded leopard, Indian leopard, wild boar, and giant squirrel. In 2018, golden and spotted Asiatic golden cats were recorded in the reserve for the first time. So you can still pay a highly rewarding visit.