Global recognition for Hrid Majharey, and our take on Shakespeare

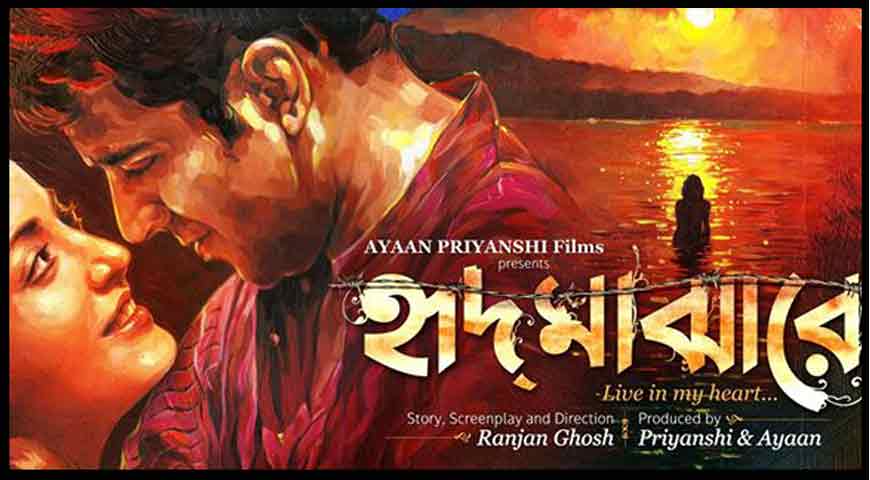

Young filmmaker Ranjan Ghosh’s directorial debut Hrid Majharey (2014) fell flat on its face at the box office when it was released in Kolkata. The film, which was intended by the director as a tribute to William Shakespeare on his 450th birth anniversary, completed exactly seven years on July 11, largely unremembered by the audience for which it was made.

However, that it has by no means been forgotten by the rest of the world was proved by the 11th World Shakespeare Congress, hosted online by the National University of Singapore from July 18-24 this year, where the film had a special screening. According to Ghosh, the event, which is held every five years, “regenerates understandings of Shakespeare across the world, bringing together scholars whose geo-cultural vantage points for working with Shakespeare both overlap and differ”.

Ranjan Ghosh

Ranjan Ghosh

Of course, this is not the first time that Hrid Majharey has received international recognition. In end-April 2016, a conference on ‘Indian Shakespeares on Screen’ was jointly organized by the British Film Institute and the University of London to commemorate 400 years of the Bard’s death. The organisers felt that Hrid Majharey incorporates “stylistic elements, themes and narrative devices that make it both self-reflexive and in keeping with Shakespearean traditions. Debutant director Ranjan Ghosh’s cinematic treatment of Hrid Majharey through intertextual references and mise-en-scene are refreshing and effective precisely because it is able to circumvent the colonial implications and gravitas of Bengal’s literary/cultural heritage – frameworks that are usually employed in a discussion of Shakespeare in Bengal – modifying and playing with Shakespeare’s characters/styles in order to make his own statement about what Shakespeare means to a contemporary audience”.

“Drawing on Othello, Hamlet, Julius Caesar and Macbeth, Ranjan Ghosh’s debut film Hrid Majharey (Live in my Heart, 2014) throbs with intertextual references and mise-en-scene that bears the imprints of a classic Shakespearean tragedy,” wrote Priyanjali Sen in her paper presented at the conference, titled ‘Shakespeare and Contemporary Bengali Cinema: Form, Intertextuality and Mise-en-scene in Hrid Majharey (2014) and Arshinagar (2015)’. Arshinagar, incidentally, can be seen as Aparna Sen’s contemporary, urban and very stylised take on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Ghosh, a Whistling Woods alumni who wrote the script for Aparna Sen’s Iti Mrinalini, tells a story of intrigue rooted in love and its loss in Hrid Majharey. The story explores these themes mainly from the point of view of its protagonist Abhijit Chatterjee (Abir Chatterjee), a professor of Mathematics popular among his students. A chance encounter with a woman soothsayer in a city restaurant, and her dark and ominous comments, trigger a catharsis in him.

From a rational, sensible man with a scientific bent of mind, Abhijit is slowly sucked into a vortex of chance, which he comes to believe is ruling his life, particularly after he falls in love with a beautiful cardiologist (Raima Sen).

Much like Shakespeare’s tragic hero Othello, Abhijit finds life spinning out of control, which worsens when the couple moves to the Andaman Islands in the hope that a change of scene will bring Abhijit back to normal. Ranjan keeps the film open-ended, with two alternative closures leaving the audience to take their pick.

Technically, the film is beautifully made with some of the most outstandingly aesthetic cinematography (Shirsha Ray) one has seen in recent times. The music (Mayookh Bhaumik) is melodious and mood-centric. Kaushiki Chakraborty’s lilting voice enriches the songs lip-synced by Raima. The soundtrack is filled with bird cries, footsteps on the floors, and ambient sound is good too. The production design ranging from the corridors of the college to the staffroom and the playground, Abhijit’s home with the sister and the artist boyfriend adding a bit of bonhomie, the unsmiling old family retinue, the apartment in the Andaman Islands, the small trip to Cellular Jail, is praiseworthy.

Says Ghosh, “I am truly proud about my film being featured by the International Shakespeare Association and the National University of Singapore. In June, the film was also part of the European Shakespeare Conference 2021, organised by the European Shakespeare Research Association and the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece.”

In 2015, Hrid Majharey was also included in a PhD thesis entitled ‘Shakespeare and Indian Cinema’ at the Tisch School of Arts at New York University. The Film Faculty at the Tisch School of Arts felt that Hrid Majharey was refreshing in that it successfully managed to break away from any colonial implications linked to Bengal’s British past, by giving it an entirely independent and topical feel.

In the same year, the Oxford, Cambridge and Royal Society of Arts Examination Board (similar to India’s CBSE) enlisted Hrid Majharey as a reference film grouped within ‘World Adaptations of Othello’ in the syllabus for its A-Level Drama and Theatre course under the title Heroes and Villains – Othello. Among the nine films included in the course are films such as A Double Life (USA, 1947), All Night Long (UK, 1962), Catch My Soul (USA, 1974) and Omkara (India, 2006).

In India, the earliest documented reference one could discover is Shakespeare Through Eastern Eyes by Ranjee Shahani, published in 1932 at the height of Indian nationalism. Shahani aspired to bring out an Indian response to the plays by taking into account differences between race, culture and ethnicity. Smarajit Dutt’s critical texts on Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth carry the subtitle ‘An Oriental Study’ and are emphatic about describing their critical objectives. Other scholars have tried to bring out comparisons between Kalidasa and Shakespeare by prioritizing Kalidasa over Shakespeare, concluding that while Kalidasa inscribed a national identity, Shakespeare could be termed “provincial.”

Franco Zeffirelli, who made three Shakespeare adaptations on film, namely The Taming of the Shrew (1966), Romeo and Juliet (1968) and Hamlet (1990), presents the ideal recreation of Shakespeare on film when he says: “I have always felt sure I could break the myth that Shakespeare on stage and screen is only an exercise for the intellectual. I want his plays to be enjoyed by ordinary people.” In this sense, Vishal Bharadwaj’s Shakespeare trilogy and Ghosh’s Hrid Majharey will stand the test of time, space, culture, and language.