‘Galakata Gali’ and murderous robbers, crime in old Calcutta

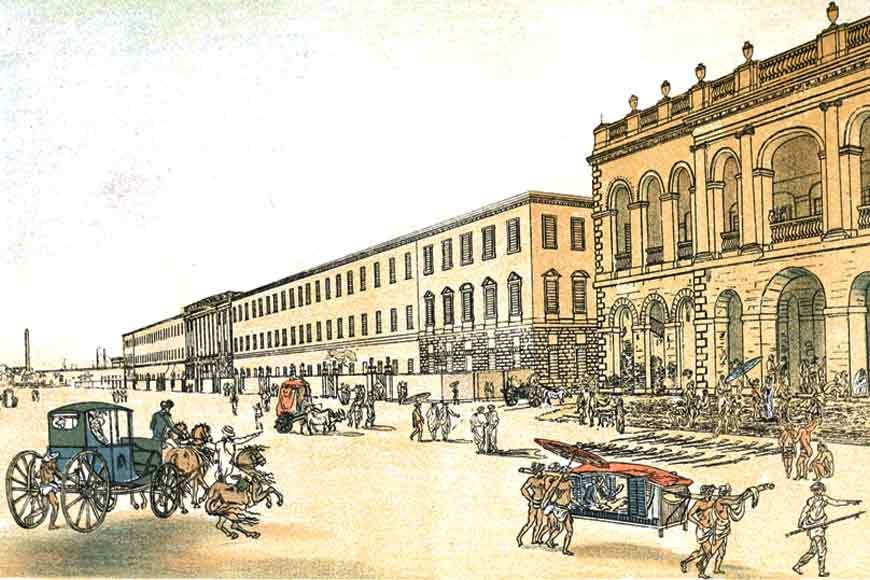

Calcutta Supreme Court from a print by Thomas Daniell, 1786

In the past, we have written about how Calcutta Police was the world’s first police force to set up its own fingerprint bureau in 1897, or how the brutal murder of a young Anglo-Indian woman in 1868 gave birth to the Detective Department of Calcutta Police, the first such department in India. Today, however, we would like to go further back, to the Calcutta of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when the system of crime and punishment was taking concrete shape, as the city upgraded itself from a cluster of settlements into a proper metropolis.

In the early days of Calcutta, as its permanent population grew, so did its ‘floating population’ of temporary residents, including a fairly large number of fortune-hunting Europeans. These were mainly soldiers and odd jobs men who had drifted to the city, and were not hesitant about grabbing an extra few rupees, wherever and however they could. It was extremely unsafe, for instance, to cross the Maidan at night, right up to the end of the 18th century, owing to frequent robberies and assaults by vagrant Europeans and occasionally even by soldiers from Fort William.

The Calcutta Gazette had this to say on September 1, 1791: “Last night about 1o o’clock, a very daring robbery was committed near the new Fort on Mr. Massuyk, who was in his palanquin, by eight Europeans, supposed to be soldiers. After wounding him severely, they took from him his shoe-buckles and every valuable he had about him.” The new Fort is, of course, the present day Fort William, which was still relatively new at the time, having been completed in 1773. As for those wondering why the robbers would want shoe buckles, the answer is that the wealthy in those days often wore buckles of gold or silver, occasionally studded with precious stones.

A view of Calcutta in 1878

A view of Calcutta in 1878

In fact, burglary and murder had become so common in certain parts of Calcutta that Fordyce Lane in Lebutala, near the Sealdah end of Bowbazar Street (B.B. Ganguly Sarani), became popularly known as ‘galakata gali’, the literal English translation for which would be Cutthroat Lane. In adjoining Colootollah (Colootola today), a burglary caused a sensation owing to the sheer number of burglars involved. The report which appeared in the Calcutta Gazette on October 22, 1789 read: “Last Saturday night fifty dacoits, Portuguese and Bengalees, broke open the house of Choitun Dutt at Colootollah and plundered it of about 6,000 rupees in money and goods. Choitun Dutt in attempting to resist, received several blows which had very nearly occasioned his death.” However, even by contemporary standards, Rs 6,000 for 50 men does not seem like a very profitable return on investment!

Whatever the gains, the punishment for burglary and robbery was harsh. The Supreme Court, also called the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William, was set up in Calcutta in 1774. At its first Criminal Sessions, held in 1795, the court tried five Europeans and one Bengali for burglary, and sentenced them to death. As was the custom of the time, the place of execution or hanging was located as close to the crime scene as possible. The idea was to have condemned criminals executed in the open near the place where they had committed their crimes, in the hope that such a public exhibition would act as more of a deterrent than ordinary punishment.

As the 19th century set in, however, the ‘places of execution’ began to become rather more permanent. The Sheriff’s records upto 1825 show that executions were mostly carried out at the ‘usual place’, which seems to have been ‘near the Coolie Bazar’ in Hastings, somewhere in or near the north of the present Khidirpur bridge, where Maharaja Nandakumar was also supposedly and famously hanged in 1775; but after 1825, the records mention a ‘usual place’ of execution immediately to the south of the jail (Presidency Jail).

The gallows and pillory (a wooden framework with holes for the head and hands, in which offenders were imprisoned and forcibly exposed to public abuse and ridicule) were set up whenever required by a contractor named Joseph Simpson, who also supplied carts for carrying prisoners to and from the jail.

What about crimes committed offshore? The answer is quite gruesome, actually. If an offence was committed on board ship, those condemned to death had a separate place of execution called Melancholy Point, on the opposite side of the river from Calcutta, just below what is now Botanical Gardens. The prisoners were rowed there on a barge on which the gallows were erected, and duly hanged. A row of gibbets (upright posts with projecting arms to hang bodies of executed criminals as a warning to others) stood on the shore, from which the bodies were suspended in chains, until they decomposed.

Ships coming to Calcutta, therefore, were treated to the horrific sight of bodies hanging in chains on the shore. Thankfully, the practise was abolished after 1820, and the bodies of executed criminals began to be dumped in the river off Prinsep Ghat. This continued until 1855, when better sense prevailed and the dead began to be cremated or buried according to their faith.

In the next edition of this article, we will cast a more detailed eye on other varieties of punishment, as well as India’s judicial system as it took shape in the British city of Calcutta.