From Utopia to Dystopia: 'Sultana’s Dream' Reveals a Haunting Reflection on Women’s Struggles against Violence – GetBengal story

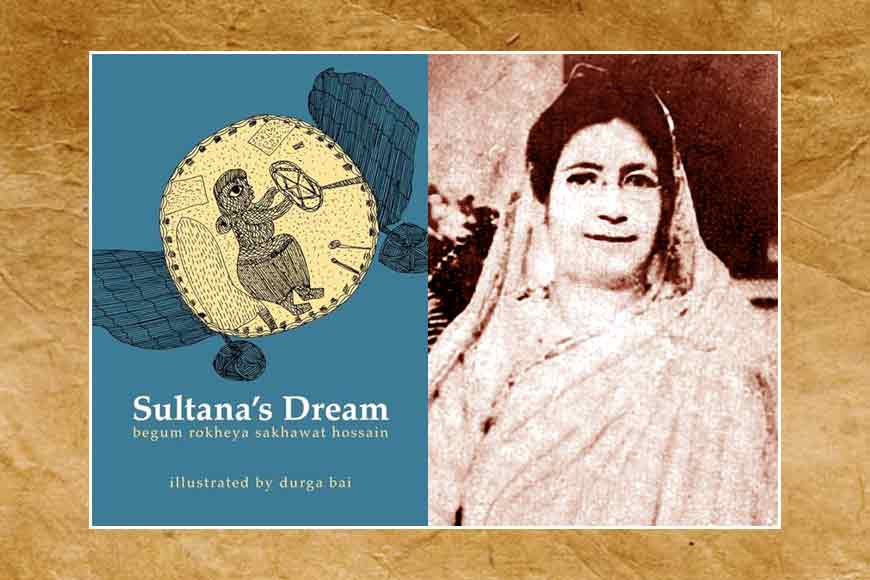

Book cover of Sultana’s Dream, Begum Rokeya

I stumbled upon a short animated film called Sultana's Dream, 2022, on a streaming platform, and intrigued by the art and synopsis, I gave it a watch. I have not been able to stop thinking about it.

A three-part series called Lost Migrations, the films deal with concepts of grief, identity, and violence against women. One of the films is Sultana’s Dream, inspired by a feminist classic of Bengali literature of the same name by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. This animated short looks back on the violence inflicted on women following the partition of India. Beautiful and achingly bittersweet, it depicts moments in these women’s lives who were violated in the name of nationalism.

Created by Sandhya Visvanathan, Aniruddh Menon, Shoumik Biswas, and Aditya Bharadwaj in 2022. The short 10-minute animated film on MUBI starts with a narration that will send chills down your spine.

During the Partition of India “Some eighty-three thousand women were abducted and raped. Abducted women who returned were often turned away by their families.”

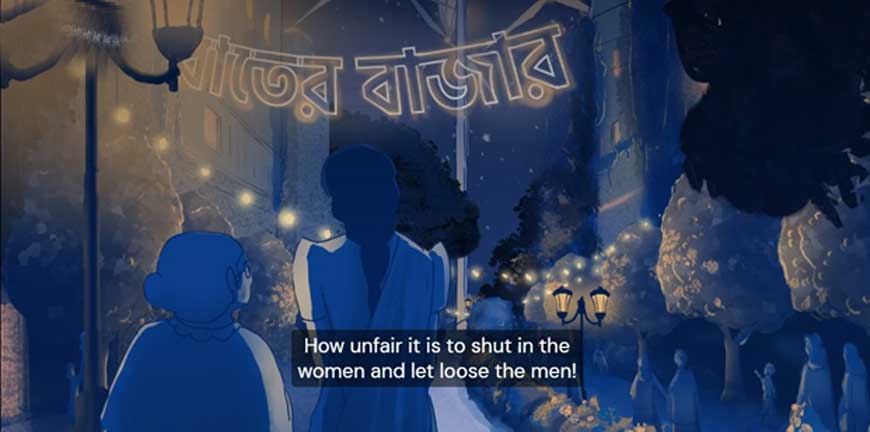

The animated short, Sultana’s Dream, 2022

The animated short, Sultana’s Dream, 2022

The film begins with an elderly woman who lives in Calcutta dreaming of a fantasy world where women live peacefully without the presence of men in open society. Brightly lit streets and lively ateliers where women labour quietly are features of this idyllic new world, but this utopian vision is followed by a harsher reality, as we see glimpses of the horrors women had to go through during the partition. We see a pregnant woman fleeing from her home and throwing away her valuables as she stares at the barrel of a gun. Another scene shows a woman complaining about their choice of hiding place. “Why here?” she asks her companion. “This is the first place they will look.” The reply she gets induces goosebumps: “Because... The well is already full.” The finality of this line, the resigned acceptance of their fate, is bone chilling.

Through vivid animation that fuses traditional and modern techniques, these striking animated films bring up questions of identity, culture, and society. But it also raises the evergreen question of women’s safety, a theme that is at the core of Sultana’s Dream (2022). A utopian vision for the future where women thrive is shattered by images of reality. From forced conversion to abduction and rape, the plight endured by women in the aftermath of the partition paints a harrowing image of the world. History lessons in motion—these excursions to the past witness the dark reality of society.

I was prompted by this movie to look into the book and author that served as its inspiration. I discovered that Sultana’s Dream, written by Begum Rokeya, was recently added to UNESCO’s “Memory of the World” list along with 20 other items from all around the world on May 7-8, 2024. This honour was given at the 10th General Meeting of the Memory of the World Committee for Asia and the Pacific, which took place in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, as part of the 2024 cycle. This is an initiative that aims to preserve and share the world's documentary heritage, ensure universal access to the document, and raise awareness of the document’s significance.

Sultana’s Dream was the first 'self-consciously feminist’ utopian story written by a woman in English. Certainly the first by an Indian woman. Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain wrote Sultana’s Dream, her first book in English, in 1905. She was probably 25 years old when the story was published. First printed in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine, a Madras-based English-language periodical edited by and for women. It was unusual for a bunch of reasons. She was among the very first Muslim women to be a part of the journal, and even rarer than that was the unique approach she had chosen to portray the themes of her story that championed women’s liberation.

But even before the publication of Sultana’s Dream, she had already garnered a significant amount of attention as an essayist, having written a number of articles in Bangla about the repression and systemic oppression of Bengali women. During her time, women were not allowed to learn Bengali or English. But Rokeya learnt both; in fact, she knew five different languages.

Begum Rokeya’s husband, who was an appreciative audience of her work, called the story “a terrible revenge." But Rokeya’s urge to write Sultana’s Dream was perhaps a reaction to the prevailing oppression and vulnerability of the women of her time and not revenge.

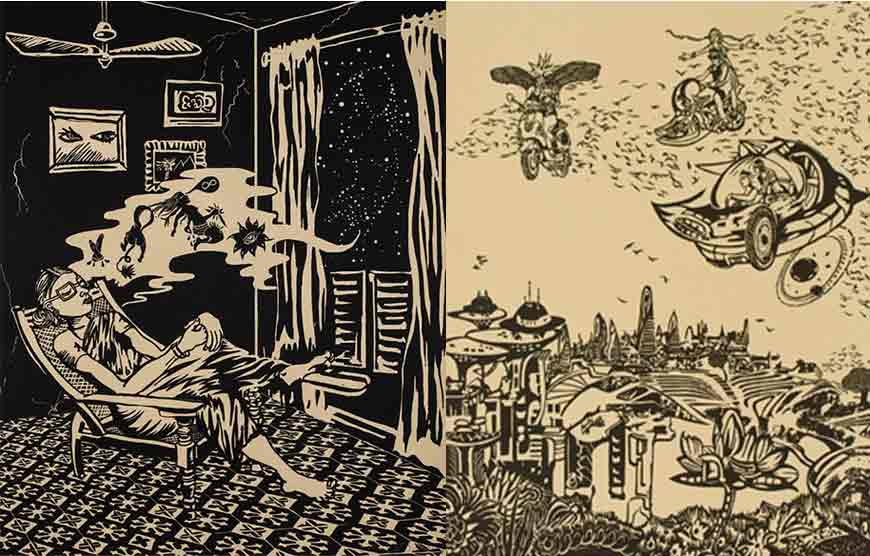

In the story, Rokeya reverses the roles of men and women. Sultana, who is the narrator of the story, is a representation of our society, where women are sequestered at home. Whereas Ladyland, the utopian world she is whisked off to, is the exact opposite. Sultana is hesitant to venture out at first as she asks, ‘Isn’t it unsafe for women out there?’ but soon learns that 30 years earlier, during a war that killed off most of the nation’s men, the surviving males were ordered to live within the walls of the mardana (a zenana for men).

Thomas Newton, for the Lady Science magazine noted that:

“In Rokeya’s feminist utopia, women rule the world as society lives peacefully and prospers through their inventions of solar ovens, flying cars, and cloud condensers, which offer abundant, clean water to the population of “Ladyland.” And the men, who are deemed “fit for nothing,” are shut inside their homes.”

Linocut by Chitra Ganesh, 2018

Linocut by Chitra Ganesh, 2018

Begum Rokeya was born to a well-educated Muslim family in the Bengal Presidency. After the death of her husband in 1911, she established The Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ High School—now run by the West Bengal Board of Secondary Education—and is still open today. Although hindered by society, she continued to fight—going door to door, trying to convince families to send their girls to school.

It’s been 112 years since the publication of Sultana’s Dream, and I ask myself as I peruse the bleak news cycle every day, 'Has anything changed? Are we close to the utopia that Sultana dreamed of?’ The answer is a resounding NO. Begum Rokeya waged a lifelong and relentless jihad (war) against some of the most terrible yet unchallenged realities of her society. This is probably why she did not continue to write in English and chose Bangla instead because she believed her pen was a weapon in her crusade towards social reform.

In 2013, Rafia Zakaria, a columnist for Dawn, wrote:

“In Sultana’s Dream, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain is careful to underscore how the toleration of suffering enables its persistence. The women who bear it in silence allow the perpetuation of oppression and are complicit in its persistence.”

As I researched to write this article, I went through the historical records of the Rawalpindi violence of 1947, and the things I read made me tear up again and again. Women being beaten, used as a weapon in the war against communities, forced to strip naked and parade on the streets, only to be raped and then burned alive.

They say history repeats itself. But we must not let history repeat itself. We must ensure our voice is heard. A century ago, Rokeya ridiculed our society’s customs and stereotypes in her works. It's a shame that we continue to fight for the right to live, the right to work, and the right to be safe every single day. When will this never-ending battle end?

"This short book is a window opened too briefly onto a world whose exoticism is overshadowed only by its oppressiveness. Particularly chilling is Hossain's work's relevance to our times."

—Publishers Weekly

The animated short, Sultana’s Dream, 2022

The animated short, Sultana’s Dream, 2022

I believe it is important to revisit the social ills that plagued Begum Rokeya, particularly since we’ve made so very little progress since then. Today, when the bigotry of gender norms and the prevailing toxicity of our patriarchal society have become prominent issues in an increasingly dystopian world, Begum Rokeya’s story and the art that it has inspired have become more important than ever.

Source: Sultana's Dream and selections from The Secluded Ones by Rokeya Begum, published by Feminist Press