First Toto dictionary, keeping an endangered language alive :Interview with Bhakta Toto - GetBengal story

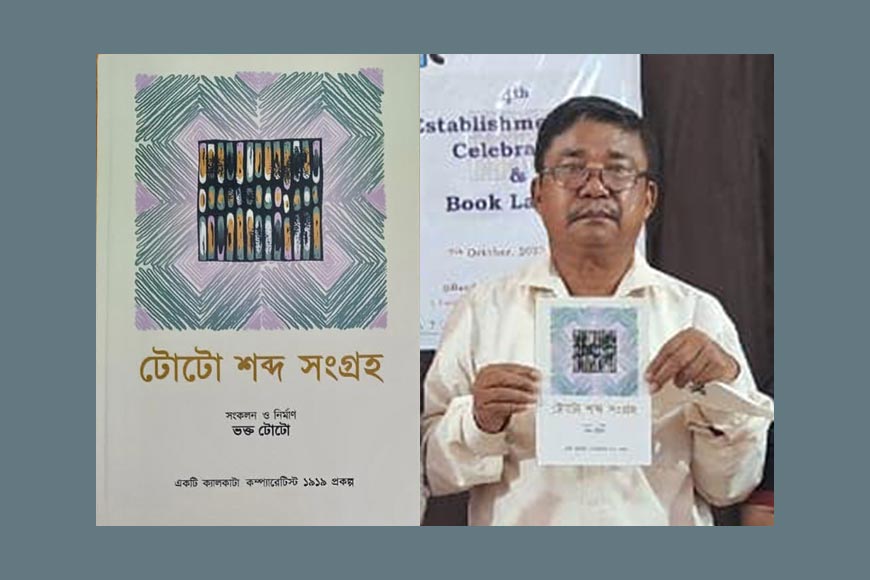

Bhakta Toto pioneers the first Toto dictionary, ‘Toto Shabdo Sangraha’ or ‘Collection of Toto Words’

TThe illusive paintings on the rocks of Bhimbetka, the mellowed signs of Harappa or even the gorgeous frescos lighting up the dark caves of Ajanta has a bond of existence – that of human’s penchant for expressing their inner feelings, their words into script, their verbal talks to be preserved down generations in a written or painted form. The same yearning is reflected in Bhakta Toto’s creation of the first ‘Dictionary’ of Toto words, a language that was fast vanishing from the face of the world. At the fag end of his career as a bank employee, a mile away from his retirement, Bhakta of Totopara, Alipurduar had to leave behind a legacy to keep his language alive and afloat. Bhakta Toto is the ‘language scientist’ trying to preserve this endangered language, his mother tongue, not allowing it to be erased from the face of the globe, when not a single of his successors would be able to speak or write the language that had been the language of his forefathers.

Bhakta Toto told GetBengal: “I do not wish to call this work of mine a dictionary, rather it is a humongous work I tried to do by translating the words we commonly use in the Toto verbal language. I translated the words into English and Bengali, so that a larger section of Bengal and India can relate to the words, speak, and understand our language.” Bhakta Toto’s dream project has successfully made a collection of more than 1200 words used by the Totos that will help the future researchers and even the lay person to understand them better. It is called ‘Toto Shabdo Sangraha’ or ‘Collection of Toto Words’ and the compilation needed decades of hard work to complete.

“Through this collection I wish to make my language more popular,” he added. True to his words, he has been relentlessly trying to keep a language afloat that was almost dying, and spread the beauty of his culture beyond language barriers, so that even the non-Totos would one day easily relate to their way of life.

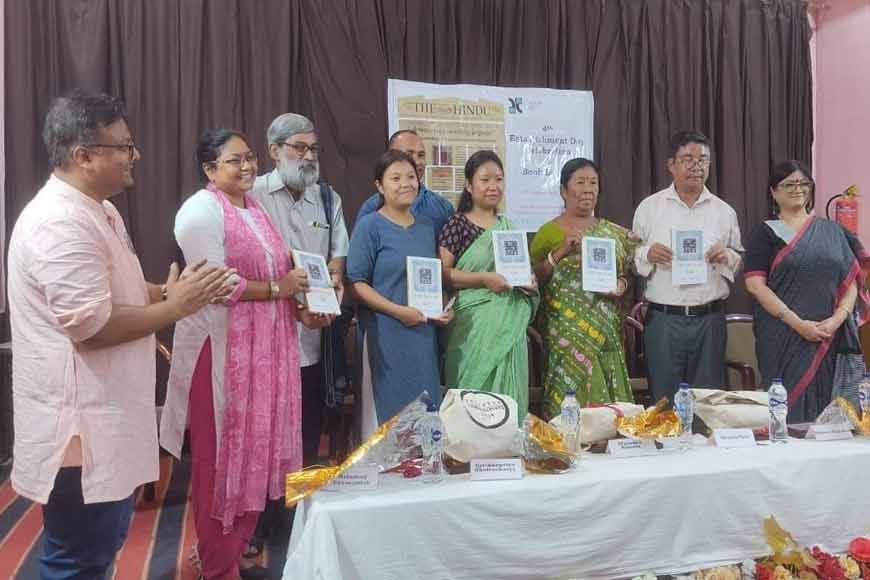

Surprisingly, Totos did never have a script of their own. It was Padmashree award winner Dhaniram Toto who stole the show a few years ago by writing the first ever script in Toto language and now Bhakta Toto has translated the words forming a ‘Word Book’ that will further boost the meaning of the scripts written and take it to the world forum. How was the response to his endeavour? Bhakta Toto is pleased at how Kolkata’s Bhasha Samsad published his work in the form of a word book so that it can reach a bigger audience. “This August (2023) my work was finally published, a work that took me years of meticulous interpretation, talking to people of Totopara, speaking to elders of my own family, to include as many words I can and translate them, finding their meanings in Bengali and English. There are more than 800 pages in the book and more than 1200 words that are presently used. But I shall try and find more words in future and this work will go on as long as I live even after my retirement as a bank employee.”

Bhakta Toto’s mother tongue is a language spoken by barely 1,600 people living in parts of West Bengal bordering Bhutan. It is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken by the tribal Toto people and since they do not have a complete script, other than the work started by Dhaniram Toto that is still in progress, most of the Toto words are written in the Bengali script. “Even the book by Padma Shri Dhaniram Toto, titled Dhanua Totor Kathamala, was written in Bengali. In my word bank too, the Toto words translated into Bengali and English, have been composed in the Bengali script, as the Toto script is still in a nascent stage and members of the tribe are more familiar with the Bengali script when they read,” explained Bhakta Toto.

Teesta Bose who did her post-graduation in comparative literature and is teaching in a government college said: “Bhakta Toto’s book is historic, as the community did not have any collection of words in a published form. Mr. Toto’s book is in Bengali script but will help everyone to understand the meanings of their words better as they are translations and in future will help many research scholars researching in endangered languages to proceed further with one of the dying languages of Bengal.”

Bhakta Toto was born in 1964 in Madarihat block of Alipurduar. His early days were spent studying in his mother tongue in the village school, from where he was sent for primary and higher education to Coochbehar and then passed his school level exams from Jorai. “I was the second student of my community to pass the Madhyamik in 1981,” said a beaming Bhakta, reminiscing his difficult childhood when expression in written language was a barrier within his immediate circle. Other than his job, he loves writing poems and essays and often helped language researchers in their work. “That’s when the idea of this ‘dictionary’ was born, as I realised that unless my language is preserved through translations, it will be confined within the narrow circles of a small community and one day get lost forever.” He hopes the younger generation will understand the depth the importance of his work and carry forward his legacy.