exclusive-for-this-pakistani-his-love-for-bengali-has-opened-the-world-to-him

At just 25, Mohammad Tahir Wahid has become a force for change. Breaking through numerous social and familial barriers, the young Pakistani is studying Bengali literature, immersing himself in Rabindranath Tagore, Nazrul Islam, Jasimuddin, and Farrukh Ahmad.

Born in a village in Gujranwala division near Lahore, Tahir’s mother tongue is Punjabi. He also obviously speaks Urdu, the national language of Pakistan. Bengali has never been a part of his ecosystem. Nonetheless, as he finished school, Tahir announced that it was his dream to learn and study Bengali.

His family’s humble circumstances meant they could barely afford to send him to university, least of all to study Bengali. How would he make a living out of it? Of what use was Bengali in a country like Pakistan, where Urdu, Punjabi, and English are the ruling languages?

His family’s humble circumstances meant they could barely afford to send him to university, least of all to study Bengali. How would he make a living out of it? Of what use was Bengali in a country like Pakistan, where Urdu, Punjabi, and English are the ruling languages?

Undeterred, Tahir left Gujranwala for Karachi, and got himself admitted to the Bengali department at Karachi University, with support from department head Abu Tayyub Khan, a name he keeps going back to during our conversation. Having arrived in Pakistan from Bangladesh in 1974 following the Liberation War, Prof Khan completed his education at Karachi University, right up to a PhD. Set to retire this year, he has been the driving force behind Tahir’s academic career.

Having already graduated in Bengali, Tahir says the Bengali department has a mere four or five students, and each year, a few students leave for other subjects despite initially enrolling for Bengali. Not Tahir, though. Because he had realised early on that in order to study a language, one had to intimately know the people and cultures associated with it. And so he began making more friends in Bangladesh.

Having already graduated in Bengali, Tahir says the Bengali department has a mere four or five students, and each year, a few students leave for other subjects despite initially enrolling for Bengali. Not Tahir, though. Because he had realised early on that in order to study a language, one had to intimately know the people and cultures associated with it. And so he began making more friends in Bangladesh.

The Covid lockdown within days of his admission to the university put an end to offline classes, and Tahir found online classes weren’t really ideal for learning the language. So he devised his own solution, watching numerous Bengali plays and series online, and learned how to speak in Bengali within two years.

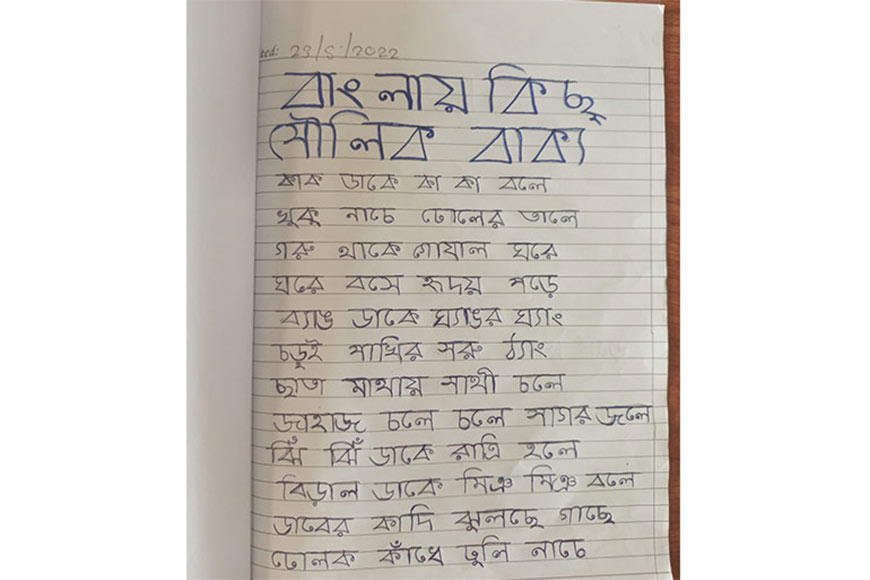

His course syllabus includes the Bengali alphabet and script, grammar, poetry, Islamic literature, a history of Bengali literature, philology and phonetics, and translations from the Koran Sharif, Bukhari Sharif, and Urdu literature. He has also tried to understand Rabindranath, Nazrul, Jibanananda, Satyendranath Dutta, Jasimuddin, Farrukh Ahmad.

His course syllabus includes the Bengali alphabet and script, grammar, poetry, Islamic literature, a history of Bengali literature, philology and phonetics, and translations from the Koran Sharif, Bukhari Sharif, and Urdu literature. He has also tried to understand Rabindranath, Nazrul, Jibanananda, Satyendranath Dutta, Jasimuddin, Farrukh Ahmad.

As he told me on the phone, “My interest in Bengali was born out of my love for the Bengali community and Bangladesh. Pakistan and Bangladesh were one in the past, and then separated. Many of the current generation have no clue about the history of this separation. But I wanted to know and learn more about a language as rich as Bengali. I wanted to know how Bangladesh sees Pakistan today.”

According to Tahir, Pakistan still has about 200 Bengali enclaves, of which 132 are in Karachi itself. These areas are often referred to as ‘mini Bangladesh’, but communal tensions have led to a decrease in the number of Bengalis living in Pakistan.

For Tahir, however, Bengali literature is not just about Bangladesh. West Bengal occupies a large part of his thoughts too. Moved by stories of Bengal’s Partition, he wishes to interact with the people of Kolkata and Santiniketan. As he says, “I never really had friends in Kolkata. There was a strange feeling of hesitation. Because India and Pakistan are still declared enemies, and any contact with Kolkata would brand me as anti-national.”

For Tahir, however, Bengali literature is not just about Bangladesh. West Bengal occupies a large part of his thoughts too. Moved by stories of Bengal’s Partition, he wishes to interact with the people of Kolkata and Santiniketan. As he says, “I never really had friends in Kolkata. There was a strange feeling of hesitation. Because India and Pakistan are still declared enemies, and any contact with Kolkata would brand me as anti-national.”

Ironical, really, because history shows us that in undivided India, a majority of doctors and lawyers in cities like Karachi and Lahore were Bengali. However, those times are long gone. Today, most Bengalis in Pakistan have had to largely give up their culture. Which is why Tahir’s father, retired teacher Abdul Wahid, simply could not understand why a non-Bengali would want to study Bengali.

The youngest of six siblings, Tahir’s eldest brother has a job, and two of his sisters are married. His mother is a homemaker, and Tahir now lives in a Karachi hostel, far away from the family. Speaking to me during a tea break when he left the hostel, Tahir says, “There is a love for the Bengali language in Pakistan still, but we need to keep our eyes and ears open to see it. Similarly, my interactions with people in Bangladesh and Kolkata have taught me that just the fact that I’m Pakistani is not a drawback. Humanism ought to be the religion above all else.”

Having begun its journey in 1953 with Syed Ali Ahsan as its head, the Bengali department of Karachi University has functioned uninterrupted for 70 years. Karachi, the financial capital of Pakistan, is home to nearly 15 lakh Bangladeshi immigrants, with signboards in Bengali dotting areas such as Machhi Bazar. There are even Bengali little magazines, and various levels of education are offered in subjects ranging from ancient and medieval to modern Bengali literature, as well as other more contemporary topics.

For now, Tahir wants to spread the word about Bengali in Pakistan. “I have chosen to study Bengali over my own language. I want to encourage the spread of the language here, and translate from Urdu to Bengali. My idea is to spread love through language.”

Given the decidedly second-class status of Bengali in Pakistan, Tahir would like to travel to Bangladesh for further studies. He has already got his visa, and has created groups on WhatsApp and Facebook to teach Bengali to those Pakistanis wishing to learn it. Given the costs of higher education, he has been looking for sponsors too. We hope this dream stays alive.