Duelling, or how the British in Calcutta killed each other

A few days ago, we spoke about the ways of crime and punishment in old Calcutta. This may lead quite naturally to questions about famous trials and the justice system as it then was, and while today is not the day to talk about all of it, we can certainly go back to Calcutta of the late 18th century and cast an eye on one aspect of life in the burgeoning British settlement that led to quite a few trials.

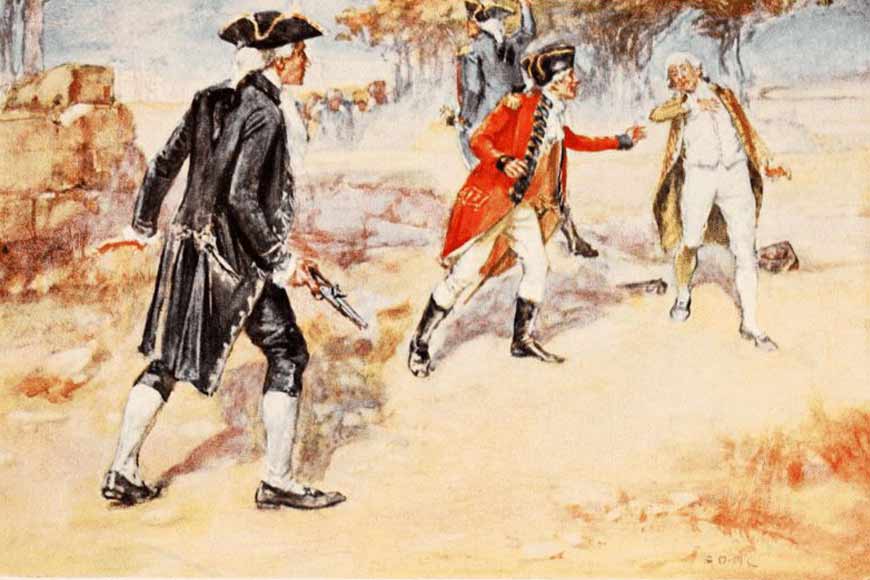

We are talking about the ancient (some would say barbaric) custom of duelling, something the British carried to India from their homeland, and practised in their adopted country with great vigour. In Medieval Europe, duelling had been the exclusive purview of knights and other members of the aristocracy, who challenged their social equals to one-to-one mortal combat with swords, spears, maces or other contemporary weapons. They seem to have fought each other mostly for king, country, love, and honour.

By the time the British arrived in India, duelling had become a far more democratic exercise, no longer limited to the likes of knights and earls. Neither were the causes as restricted, and the advent of gunpowder had opened up new ways of killing each other. In 18th-century England (and Calcutta), duels could be fought on causes ranging from an argument at a public place, to a political disagreement, to a question of philosophy or current affairs, to an unpaid debt, any pretext in short, followed by a shootout leading to serious injuries and worse.

In his 1946 book Old Calcutta Cameos, B.V. Roy wrote, “The English residents of Calcutta in the 18th Century brought this pernicious custom with them from their homeland, and duels were of frequent occurrence among them in Calcutta up to the end of the 18th Century, resulting either in death or serious disablement for one or other of the parties.”

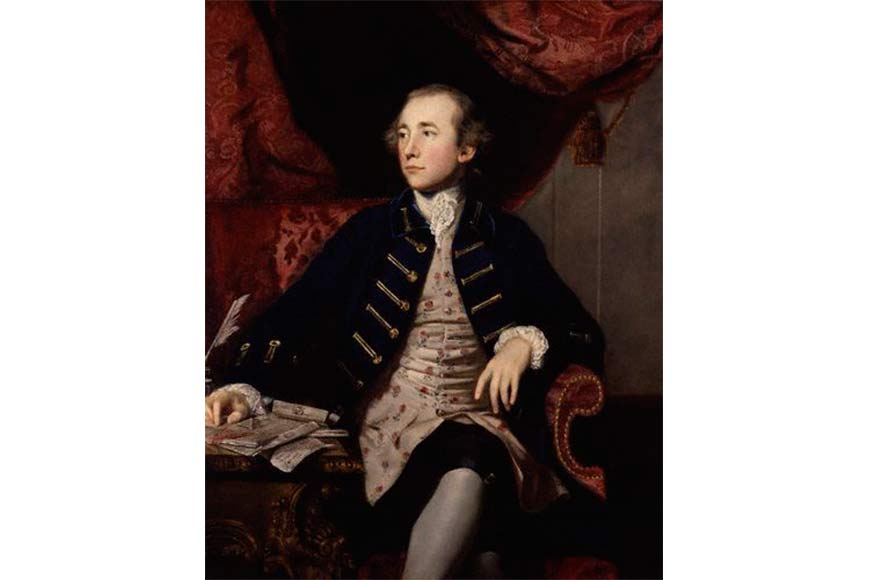

Warren Hastings

Warren Hastings

The pages of the Calcutta Gazette would often furnish instances of such duels, of which the most famous was the one fought between then Governor-General Warren Hastings and First Member of the Council Philip Francis on August 17, 178o. The famed face-off has been widely written about since then, but one of the most vivid contemporary accounts comes from the indomitable Mrs Fay, the Englishwoman whose letters have told us so much about life in the Calcutta that she inhabited. In a letter dated September 27, 1780, she wrote:

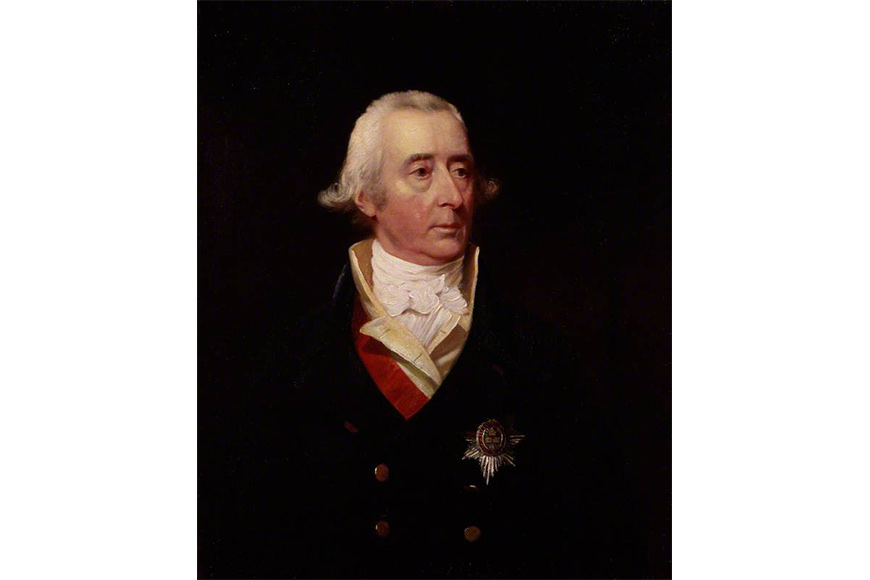

Phillip Francis

Phillip Francis

“I must relate what has occupied a great deal of attention for some days past - no less than a duel between the Governor-General and the First-in-Council, Mr. Francis. There were two shots fired, and the Governor’s second fire took place. He immediately ran up to his antagonist and expressed his sorrow for what had happened, which, I dare say, was sincere, for he is said to be a very amiable man. Happily the ball was soon extricated, and if he escapes fever, there is no doubt of his speedy recovery......... What a shocking custom is that of duelling! It always vexes me to hear of such things.........”

When she writes that the Governor’s second shot ‘took place’, Mrs Fay means that it found its target, but despite the bullet (ball) lodging in his back, Francis survived the duel. The quarrel between the two men appeared to have originated from a violent difference of opinion regarding State policy at the Council, and Hastings had written a furious and strongly worded letter to Francis. Equally livid, Francis had sent a reply which ended with a challenge to a duel.

Belvedere House painted by William Prinsep in 1838

Belvedere House painted by William Prinsep in 1838

As an ‘honourable man’, Hastings was bound to accept the challenge, and appointed Col. Pearse, Commandant of the Artillery, as his ‘second’. The role of a ‘second’ was to ensure that all the rules of duelling were properly followed, and to step in to replace the original combatant should the latter fail to show up. On the other hand, Col. Watson, Chief Engineer of Fort William, was engaged as second to Francis. The so-called ‘meeting’ was arranged for August 17, 1780, and the place chosen was Alipore, near Belvedere House, on a lane still known as Duel Avenue.

It is worth noting here that duelling had been legally forbidden in Calcutta, as in Britain, and should one party be killed, the other was liable to be tried for manslaughter. In a classic example of a social custom taking precedence over the law, however, most perpetrators were often let off with nothing more than a fine. As the Calcutta Gazette notifications show, the law had done nothing to prohibit the public announcements of deaths and injuries resulting from duelling either.

Also read : Serial horror, Bengal's Chainman killer

So we learn from a report published on July 29, 1784 that a Lieutenant White had “died on Saturday morning of a wound which he unfortunately received in a duel the preceding evening”. On May 31, 1737, readers were told that “yesterday morning a duel was fought between Mr. G, an attorney-at-law, and Mr. A, one of the proprietors of the Library, in which the former was killed on the spot. We understand the quarrel originated about a gambling debt”.

And on July 5, 1787, the public was informed that “on Monday last came on the trial of Mr. A. for killing Mr. G. in a duel. The trial lasted till near five o’clock in the afternoon, when the Jury retired for a short time and brought in the verdict, ‘not guilty’.”

Coming back to the Hastings-Francis shootout, Col. Pearse published his own account of the proceedings, and an excerpt reads: “Mr F. drew his trigger but his powder being damp, the pistol did not fire. Mr. H. came down from his ‘present’ to give Mr. F. time to rectify his priming… His (Hastings’) shot took place. Mr. F. staggered and in attempting to sit down, fell and said he was a dead man. Mr. H. hearing this, cried out, ‘Good God! I hope not’ and immediately went up to him, as did Col. Waston, but I ran to call the servants.”

Writing to his wife a few days after the incident, Hastings said, “I have now the pleasure to tell you that Mr. F. is in no manner of danger, the ball having passed through the muscular part of his back just below the shoulder, but without penetrating or injuring any of the bones.”

Which is all very well. The trial of a serving Governor-General for manslaughter would no doubt have been an awkward affair, one that the British-Indian justice system was not yet ready for. And had Francis found his mark instead of Hastings, history might have had to record the only instance of a serving Governor-General of India being killed by a fellow countryman!