Dream pay package: The salaries that lured the British to Calcutta

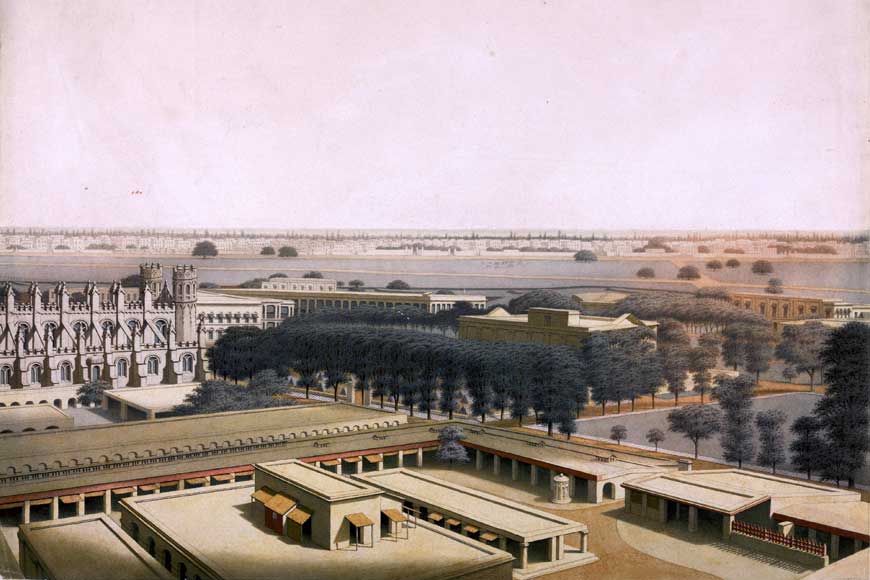

Fort William in 1828

The British knew two things about Calcutta, the city they helped create from a cluster of villages for which they had obtained leases from the Mughal empire. One, it was a city built on trade, where merchants were VIPs. Two, Calcutta and Bengal as a whole promised untold riches to those who knew where to look, and loot. Small wonder then that Britons shipped out to Calcutta in droves in the 18th and 19th centuries, as the British-Indian administration expanded rapidly and required officials and public servants of all denominations to fill mushrooming vacancies.

In the companion piece to this one, we saw how Calcutta became a wealth creator for high-ranking British officials who saw no harm in indulging in extremely profitable ‘side businesses’. However, not all of them were traders and businessmen in disguise. Many depended entirely on their salaries to make their fortunes, and these were not inconsiderable. So what kind of money did the administration offer to tempt these people?

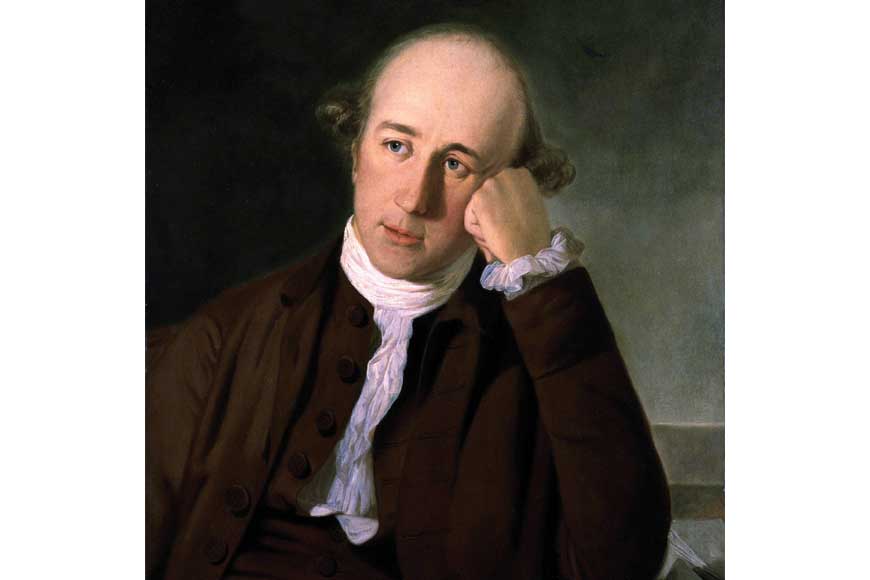

Warren Hastings

Warren Hastings

For the higher European officials under the East India Company’s government in its earliest days, the payout was handsome. With the appointment of Warren Hastings as Governor-General in 1774, four Englishmen - Sir Philip Francis, Richard Barwell, Colonel Monson and General Clavering - were appointed Members of the Supreme Council, each of whom received a salary of over Rs 8,000 a month. How much was Rs 8,000 worth in today’s terms? No reliable inflation calculator goes as far back as the 18th century, but based on 20th-century trends, a figure of between Rs 7 and 8 lakh per month seems probable.

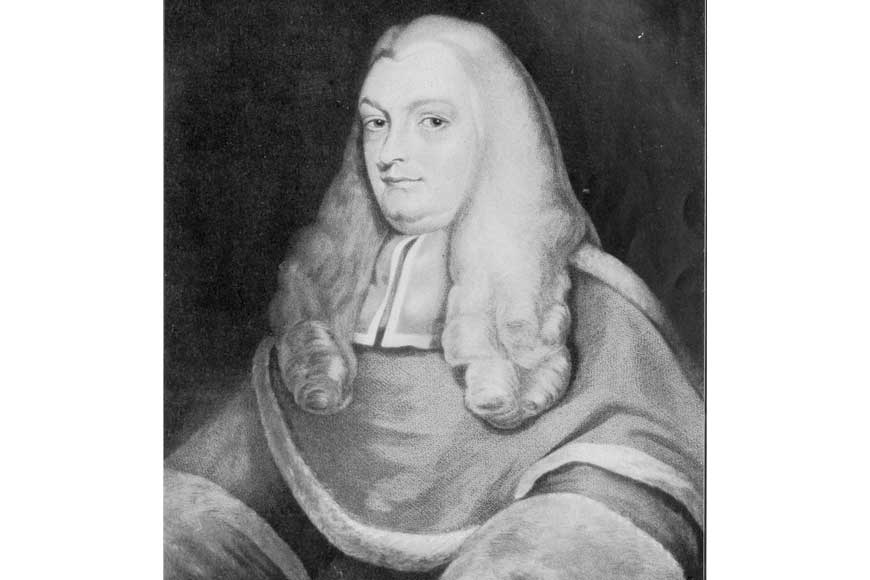

This was also the year that the Supreme Court was established in Calcutta, with Chief Justice Sir Elijah Impey drawing a salary of Rs 8o,ooo a year, and the three puisne judges (pronounced ‘puny’, inferior in rank to chief justices) - Stephen Caesar Le Maistre, John Hyde, and Robert Chambers - had Rs 60,0000 a year each. Nonetheless, in a letter written a few years later to a friend, Impey whinged that he had been unable, after five years of service, to save “more than £3,000 in any year”.

Chief Justice Sir Elijah Impey

Chief Justice Sir Elijah Impey

It is perhaps this discontent that caused one of contemporary Calcutta’s most notable financial scandals, when a relative of Impey’s named Frazer, who held the office of Sealer of the Supreme Court, was given a lucrative contract for ‘pool-bundy’, or the maintenance of bridges and embankments. The buzz was that the actual contractor was the Chief Justice himself. In fact, James Hickey wrote in his Bengal Gazette, “A displaced civilian, asking his friend the other day, what were the readiest means of procuring a lucrative appointment, was answered: ‘Pay your constant devoirs (an archaic word meaning duty) to Marian Allypore, or sell yourself body and soul to Poolbundy’...”

Hickey’s Gazette was the 18th-century version of today’s tabloids, which routinely published scandalous statements about the who’s who of the city. The irreverent Hickey had scurrilous nicknames for all prominent Englishmen and women in Calcutta, thinly disguised so as to be readily identifiable. ‘Marian Allypore’ was clearly the German baroness Marian von Imhoff, the second wife of Warren Hastings, who lived in Hastings House, Alipore, while ‘Poolbundy’ was an obvious reference to Impey for his connection with the contract.

By the mid-19th century, some of the salaries paid to judges and other officials had risen appreciatively. In 1841, for example, the Commander-in-Chief and each of the four members of the Supreme Council drew Rs 8,860 per month; the puisne judges each had Rs 5,209 per month; the Advocate-General Rs 6,945 per month; and the Judge of the Sudder Adawlut (sadar adalat) Rs 4,789 per month. Just for perspective, the first Advocate-General Sir John Day had been appointed in 1778 on a salary of Rs 3,ooo a year.

Hastings House

Hastings House

What about officials outside Calcutta? An interesting excerpt from a publication titled ‘A Young Civilian in Bengal in 1805’ by Isaac Roberdeau reads: “The salary of a Judge and a Magistrate is in no Zillah less than Rs. 24,000 per annum... The salaries of all Collectors arc the same, viz., Rs. 1 ,5o0 per month, but some Collectorships are better than others, because there is an authorised percentage drawn by these officers on the sale of Stamp Paper and on Licenses for selling intoxicating drugs and liquors, the consumption of which, of course, varies in different Zillahs. The Collectorship of Benares, for instance, is by these means worth upwards of 40 000 rupees a year... The Senior Judge of a Court of Appeal and Circuit gets Rs. 45,000, the second Rs. 40,000 and the third Rs. 30,000 a year.” The difference between officials posted in Calcutta and in the districts is obvious, though the latter weren’t exactly pauperised.

Even clergymen serving under the Company as chaplains were prone to indulge in business “on the side” to supplement their income. John Hyde’s account titled ‘Parish of Bengal’ says that “about I776, the salaries of the clergy were increased from Rs. 8oo to Rs. 1,200 a month. Church fees must have been very lucrative, because the Chaplains obtained leave to send home upto £1,ooo a year each through the Company’s bills”. Elsewhere in the book, we find: “That was the period of the much criticised Salt, Betel, and Tobacco monopoly sanctioned by Clive. If Mr. Bolt’s Considerations on Indian Affairs be correct, the Chaplain, Mr. Parry’s two-thirds share must have produced a profit of over £2,800 the first year, and over £2,2oo the next.”

What about independent professionals such as lawyers and doctors? Well, H.E.A. Cotton’s ‘Memories of the Supreme Court, 1774-1862’ uses the expression “retired with a fortune” so many times that it becomes boring. Samuel Tolfrey, for example, was an Attorney appointed Under-Sheriff to Alexander Macrabie in 1775. Hickey’s Bengal Gazette dated December 2, 1790, reports, “Samuel Tolfrey, Esq., has embarked for Europe with a fortune of three lakhs of rupees.”

Again, the name of Thomas Farrer stands first on the roll of advocates of the Supreme Court, where he was admitted on the opening day, October 22, 1774. Hickey wrote: “His most sanguine hopes were soon realised by his acquiring a noble fortune”, no less a sum than £60,000 (about Rs 6 lakh in those days) in the space of four years. Miss Sophia Goldbourne, writing in ‘Hartley House’ (1739), says: “No wonder lawyers return from this country rolling in wealth: their fees are enormous. If you ask a single question on any affair, you pay down your Gold Mohur (two pounds); and if he writes a letter of only three lines, twenty-eight rupees (four pounds)... The fee for making a Will is in proportion to its length, from five Gold Mohurs upwards...... A man of abilities and good address in this line, if he has the firmness to resist the fashionable contagion, gambling, need only pass seven years of his life in Calcutta, to return home in affluent circumstances.”

As for medical professionals, they are surprisingly far down the ladder. Take the renowned Dr Rowland Jackson, a well-known physician in Calcutta in the latter half of the 18th century. Having studied Medicine and Natural Science at several European universities, he was appointed to treat officials of the East India Company on a salary of a mere Rs 500 per month, plus Rs 200 as house allowance. Ms Goldbourne wrote: “Doctors visit in palanquins and charge one Gold Mohur a visit. The extras are enormous, such as a Bolus, one rupee; an ounce of salts, ditto; an ounce of bark, three rupees; such a lot of these commodities have to be swallowed, that literally speaking you may ruin your fortune to preserve your health.”

Calcutta Medical College

Calcutta Medical College

Once again by the mid-19th century, we find that in 1835, when the Medical College was established, its first Superintendent was Assistant Surgeon A.J. Bramley, appointed on a salary of Rs 1,200 a month in addition to the regimental pay and allowance of his rank, which would have amounted to another Rs 300-400. In sad contrast, the ‘native doctors’ in charge of small hospitals in Calcutta began their careers on a miserable Rs. 20 a month.

The first four Bengali students who graduated from the Medical College as fully qualified doctors in 1839 - Uma Charan Sett, Dwarkanath Gupta, Rajkristo Dey and Nobin Chandra Mitra - while effusively praised for having overcome social prejudice and other difficult obstacles, were recommended for government service. Their starting salary? The princely sum of one hundred rupees a month. Clearly, some doctors were more equal than others.

Given the exorbitant pay and opportunities for ‘side incomes’, Calcutta was an irresistible flame for moths in the shape of British officials. By the time the British left India, the once glorious city was in tatters, which ought not to come as a surprise.