Desmond Doig, the man captivated by Calcutta

Image Courtesy : Nepali Times

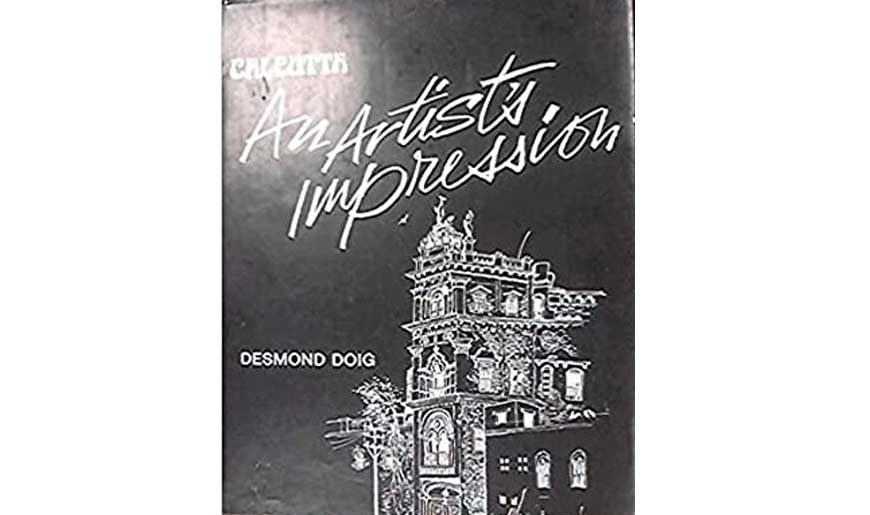

“T“To Calcutta, much abused, much loved, always interesting.” Thus reads the dedication in the book ‘Calcutta, An Artist’s Impression’, first published in 1968 by The Statesman Ltd, and later republished as a commemorative volume. The author of this remarkable book was the remarkable writer and artist Desmond Doig. Those who knew him would also add designer, photographer, expeditioner, and conservationist to that list. A man whose birth centenary passed sadly unnoticed last year.

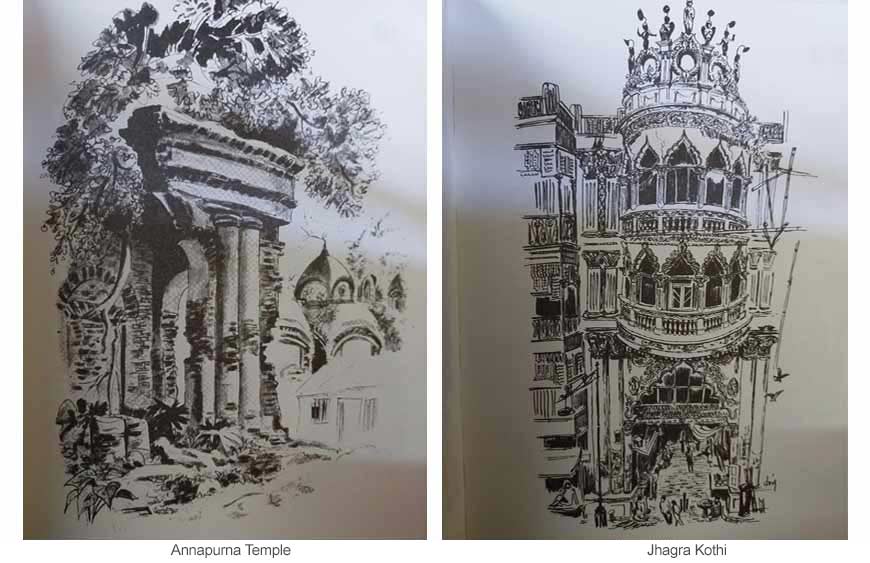

Calcutta captivated Doig in a way that no other city perhaps did, with the exception of Kathmandu later in his life. Of all his books, ‘Calcutta, An Artist’s Impression’ is the one that stands out not just for the weight of its documentation, but the loving care with which Doig sketches and writes about some of the city’s proudest landmarks, many of which have now disappeared, or are certainly no longer as proud.

Desmond Doig, second from right

Desmond Doig, second from right

Born 1921, died 1983. Of Anglo-Irish descent, alumnus of Kurseong’s Victoria School, fought with the Gurkhas in World War II. Demobilised after the war, Doig joined The Statesman as a roving reporter. Try as we might, however, we couldn’t find a confirmed date of birth or death. There is no author profile to be found in his book, and his own foreword mentions neither date nor place. One senses a reluctance to be pinned down by such mundane details, a free spirit whose bohemian nature made no concessions to the concerns of more ordinary minds.

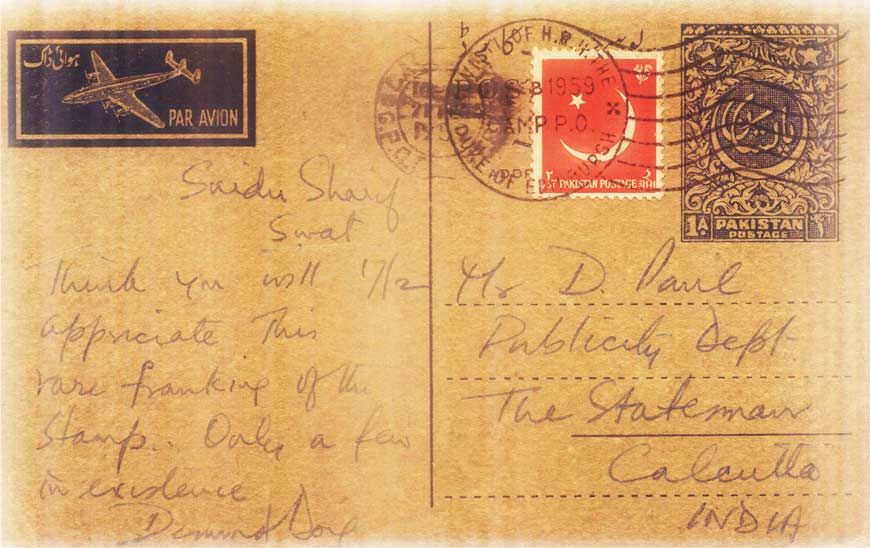

Handwriting and Signature of Desmond Doig (Collector - Arun Paul)

Handwriting and Signature of Desmond Doig (Collector - Arun Paul)

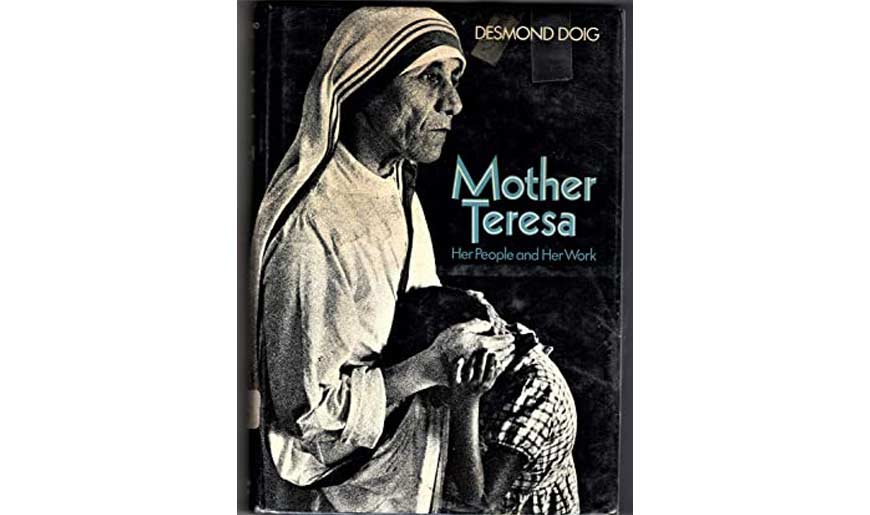

That description may sound vague, but Doig’s very concrete achievements are anything but. As The Statesman’s roving reporter, Doig exposed the terrible state of Calcutta’s government hospitals, and such was the impact of his investigations that then Chief Minister Dr B.C. Roy was compelled to order an official inquiry. Overnight, Desmond Doig became a household name in the city. He was also the first journalist in the world to write about a diminutive Albanian nun called Mother Teresa, who was picking up the dying from the streets of Calcutta and taking them in so they could spend their last few days in peace.

At the other end of the spectrum, Doig rubbed shoulders with royalty in Bhutan, Nepal, and Sikkim. And in 1963, accompanied by his ‘good friend’ Sir Edmund Hillary, he set off on a quest for the Abominable Snowman or Yeti in the high Himalayas on a National Geographic funded expedition.

His Artist’s Impressions was originally a series which captured Calcutta’s fast-vanishing old buildings and monuments. By the time he began this project, Doig was founding-editor of The Junior Statesman, the iconic youth magazine of the 1960s and 70s, referred to simply as JS. He had personally recruited a team of young journalists that included the likes of the later renowned Jug Suraiya and Dubby Bhagat, giving many of them their first jobs.

Going through the book today, it is easy to see how important the brief notes accompanying every sketch are. To take one random example, if you were to Google ‘Vijay Manzil Kolkata’, a typical result would inform you that ‘it is a wedding banquet full of timeless charm and old world elegance’, and more to that effect. Only Doig’s book will tell you that it was once the Calcutta residence of the “Maharajadhiraja of Burdwan”, that it was built in 1903, that its garden once required the constant attention of 15 gardeners, or that its stables once contained about 60 horses. The grand banquet which now hosts mega-budget weddings was where governors-general dined, with Lord Linlithgow (Governor-General, 1936–43) being the last.

A similar fate has befallen Singhi Palace, now yet another posh wedding venue. Only Doig, with his trademark wicked humour, tells you about the low boundary wall that offers a view of the house, and the extraordinary collection of marble statues flanking the driveway - “Venuses, Aphrodites, scholarly Greeks, and lesser plump females taking the sun”. That view is no longer available, but when Doig was writing, Narendra Singh Singhi was generous enough to allow “the public to use the park on occasion”. Doig also describes the home’s many priceless artefacts, a bedroom suite made of ivory, and twin beds of solid silver in another room.

Such gems are scattered throughout the book, indicating not just a deep fascination with Calcutta and its treasures, but a desire to preserve their memories for posterity.

Who else but Doig would tell you about a building solemnly called Jhagra (quarrel) Kothi, in Armenian Street off Chitpore Road? He found it “hideously attractive, even beautiful in its way”, and those who do take the trouble will still find it much as Doig did, four blocks of every architectural style imaginable, home to thousands of residents and numerous businesses. As for the name, Doig claims it came about when the building’s construction in the early 20th century caused a huge communal uproar for some reason. Today, there is nothing but “harmony and bustle”.

Let us not forget this most fascinating chronicler of Calcutta. May his memory live for another century.