Delve into the conflicting worlds of body and mind with Titane at KIFF

The Covid-19 pandemic has opened up a new, ever-changing, perilous and transitory world, and so does the film Titane, that revisits the language of ‘taking care’. This offbeat offering is for those who are equally open to the idea of ‘tenderness’ and the pain that tenderness causes. It stands in stark contrast to the human body’s inexorable processes, creating a conflicting idea. Titane moves between a bold, fearless approach and a superb sensibility. No wonder it won the Palme d’Or (Golden Palm) at Cannes.

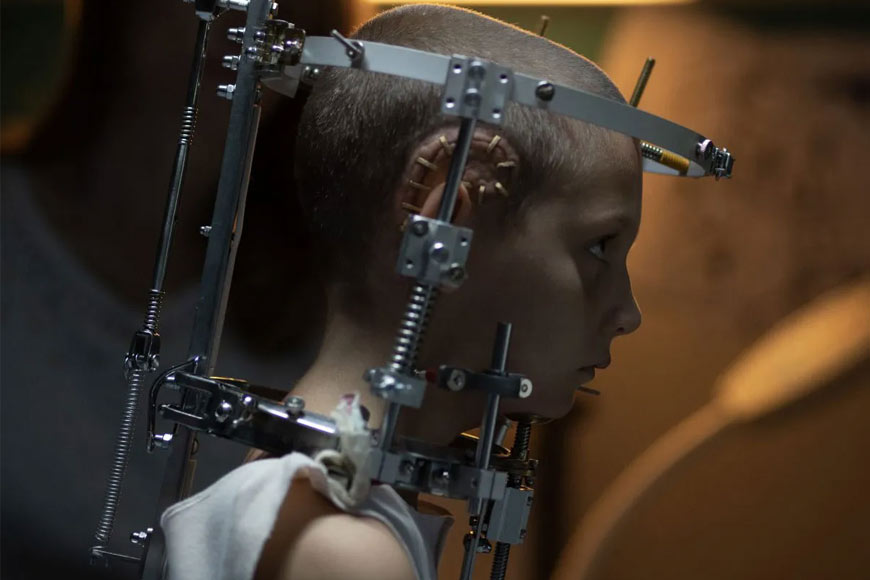

French filmmaker Julia Ducournau starts off with an interesting tatoo that reads: ‘Love Is a Dog From Hell’ imprinted between the protagonist Alexia’s breasts. The tattoo acts like a red flag for whoever tries to get close to Alexia. Alexia is the feral and compulsively murderous stripper-gearhead at the centre of Titane, named for the titanium plate holding together Alexia’s skull after a childhood car accident. The film brings out the human body’s vulnerabilities and urges, its ravenous processes, and how the collective ‘we’ attempts to deal with all of this. The lesson: ‘You can’t control the inherently uncontrollable’.

Many will leave the theatre with a feeling that something is terribly ‘wrong’ with Alexia, first seen as a dead-eyed ‘bad seed’ type child, glowering at her dad as she makes engine-revving noises in concert with a moving vehicle. She wants the car to crash, or at least wills the crash into being.

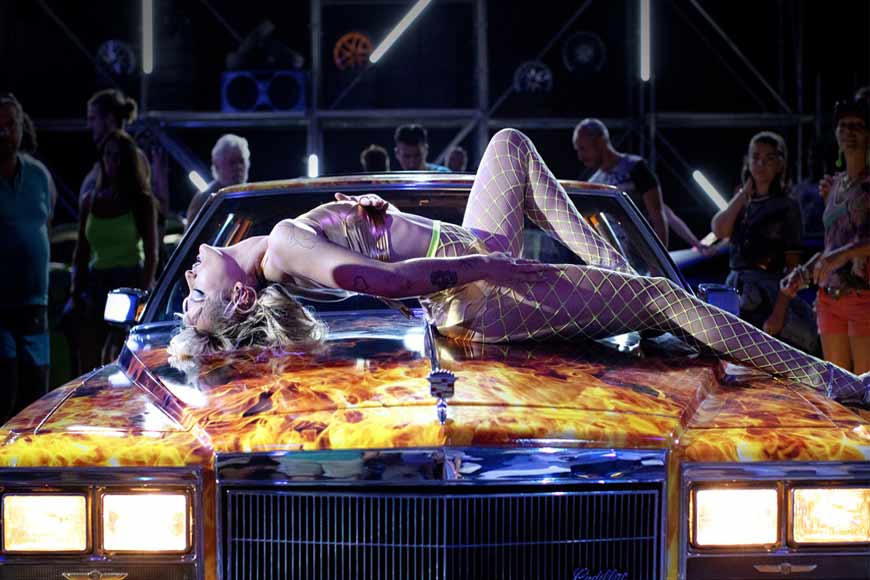

Emerging from the hospital, stapled-together scar swirling around her half-shaved head, she throws her arms around the car, kissing the window. A rapturous reunion. Years later, her head is still half-shaved as Alexia makes a living, stripping at car shows. She is a solitary and forbidding figure, even more so when she suddenly murders an aggressive fanboy who follows her to her car. Later that night, she crawls into a flame-painted gas-guzzling Cadillac for another rapturous reunion, only this time it's sexual. The car sex results in a pregnancy and titanium-plated Alexia stares in terror as her belly bulges out, her breasts leak motor oil, and black oil pours out of her vagina in the shower. Her body is now on a journey that doesn't include her.

Meanwhile, though, the bodies pile up. Alexia is a relentless murderess. These murders are gruesome in the extreme. After leaving a witness at a murder spree, she is forced to go on the run. When she sees a computer-generated image of what a famous missing child named Adrien would look like today, Alexia gets a brilliant idea. Without hesitating, she breaks her own nose, binds her breasts and pregnant belly, and goes to a police station, presenting herself as the long-lost Adrien. This is such a perverse and funny plot twist, and it signals the second half of the film, very different in feel from the first.

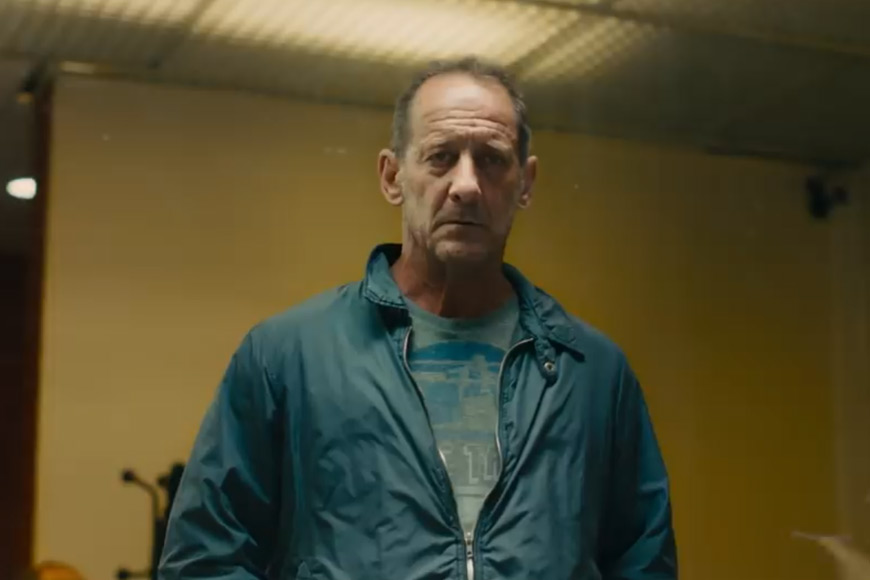

Adrien's father Vincent (an excellent Vincent Lindon) is a muscle-bound fire chief who dissolves into tears when he sees his son. But appearances aren't what they seem. Vincent isn't his surface, just as Alexia isn't hers (or Adrien isn't his). The fire house is a womanless world of macho half-clothed men, and yet the décor is gender-coded, the interior lighting a soft neon pink, the bathroom tiles bright pink.

Ducournau digs deep into her subject, moving into very strange and complex waters. Alexia is not a character so much as she is the ragged wild-eyed personification of fight-or-flight (albeit pregnant with a baby fathered by a Cadillac). But Vincent ... Vincent is a real character, revealing the confusion and little boy's fear surging beneath those muscles. The metaphors are multifold, and Ducournau smartly keeps things fluid, allowing things to work subliminally and/or visually as opposed to explicitly in the language. There's a scene where Vincent, eyes struck dumb by misery, sinks his head down into Alexia's lap. The two figures are bathed in pink light. Life moves on metaphorically and so does the body.