Creator of ‘Katum Kutum’ miniature series, Abanindranath took art to new heights!

“Atmasanskritirbarb Shilpani..” (Art is to cultivate one’s own soul)

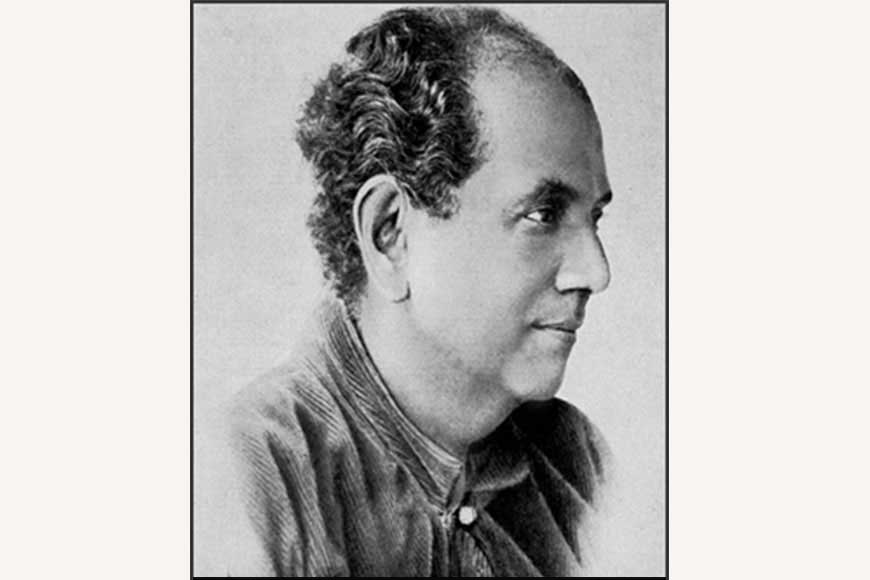

Abanindranath Thakur (7th August, 1871 – 5th December, 1951), was a pioneer artist of modern Indian art and was also a great master and a pillar of the Bengal School of Art. A favourite nephew of his illustrious uncle, Rabindranath Tagore, Obin (that’s how Rabindarnath addressed him) etched his own identity in the world of arts. He was a multi-faceted talent who induced freshness into the art scene. He was the first Indian artist to attempt such a breakthrough. In his series of ‘Bageswari Shilpa Prabandhavali’ (lectures on art), delivered between 1921 and 1929, he clarifies his views and methods of approach and discusses “the theory of beauty” and “the relationship of art and tradition.”

The master---Abanindranath Tagore

The master---Abanindranath Tagore

Abanindranath gives the artist the priority of a visionary who upsets commonly held notions of art and is free as the wind. The artist is never a slave to the technique or convention, but he dips his brush in the colors of the mind and then paints. To Abanidranath, art was like God’s majestic creation, a ‘Kriya’ or ‘Karya’ (deed) without a ‘Kaaran’ (cause) for Ananda (bliss).

Great artists do not come to build ideals of beauty, but to explore such structures as may grow from time-to-time and push them into running stream of life where Beauty and non-Beauty flow together. Art is man’s response to the overpowering mystery of nature.’ Both in his painting and his writing he had alchemy of touch, capitalizing his actual descriptions with the far-away-ness of dreams and his fantasies with strange reality, an incongruity one associates with a child’s imagination. In his lecture, ‘Vision and Creation,’ Abanindranath Tagore states that an artist’s vision should be like a child’s vision. “In a child’s vision the objects of nature are full of delight and mystery‟, he says, but when a man grows old, with all his needs, he slowly loses the freshness of this vision and comes to consider the entire world as mundane.

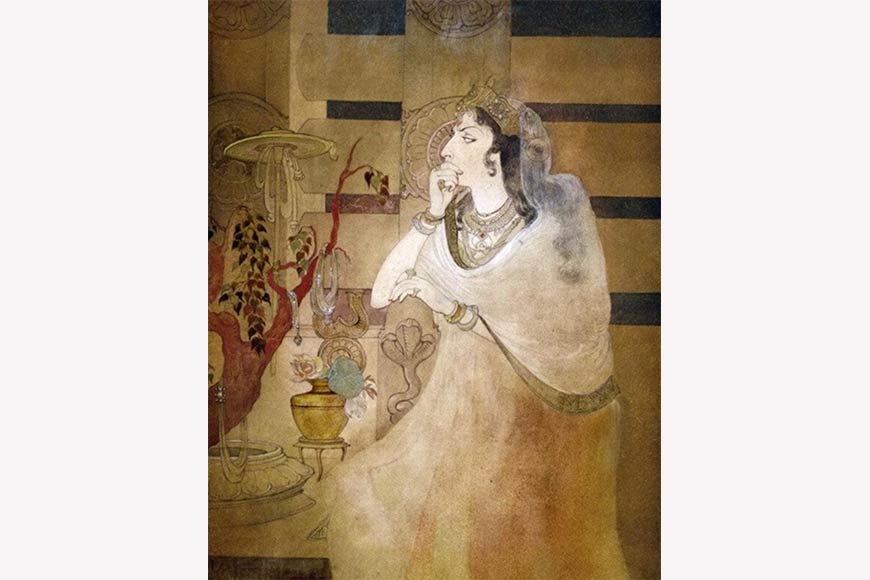

Abanindranath's work--Tissarakshita Queen Of Ashoka

Abanindranath's work--Tissarakshita Queen Of Ashoka

Abanindranath’s vision can be very well understood in his autobiography Apon Katha. His artistic sensitivity was shaped by the Indian aristocratic household of the late-19th century where he was born. He felt like a caged bird in that kind of a surrounding. He mentions how he would lean on the parapet of his ‘South verandah’ for hours and watch the city street below. He was mesmerized by the fluidity of movement and it added an aura of mystery and wonder to his receptive mind. The world of his ‘Arabian nights’ series of paintings is a stylized version of the universe he observed from his verandah.

Also read : How did the Folk Art of Alpona come to Bengal?

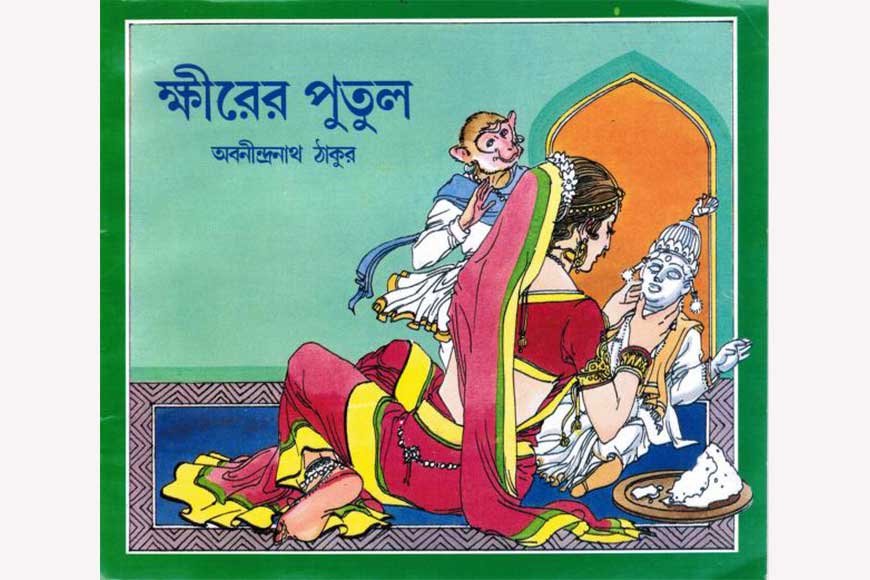

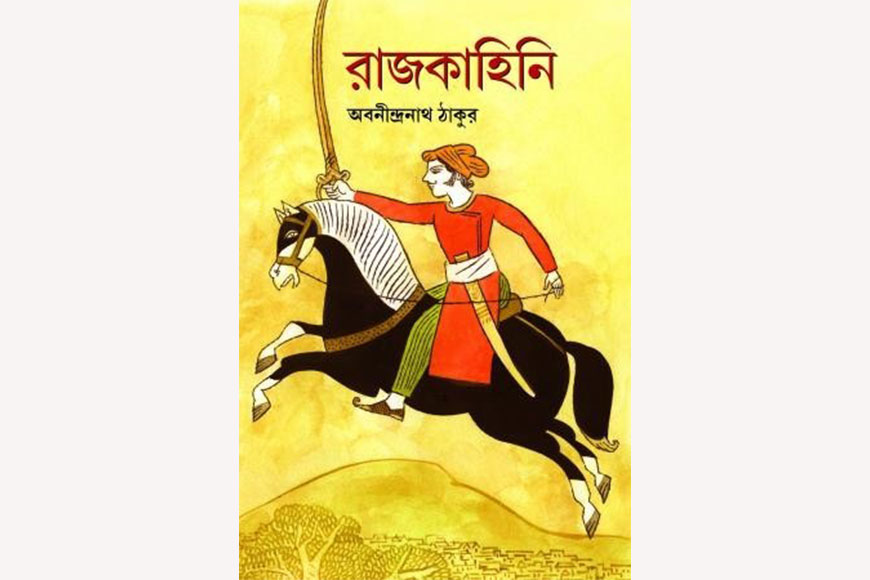

Abanindranath’s paintings and Jatra palas for adults and books written for children indicate a strong string that binds the creative mind to bear the weight of intense imagination. His books for children reflect his sensitive and intuitive mind at work. Nalak, Kheerer Putul, Rajkahini, Budo Angla are landmarks in Bengali children’s literature. The imagination of a child is not the black and white of words but that of colours of a painting. Abanindranath’s folk tales are visual texts where the opulence is brought to life through the expression of colours. Take for instance, one of his most famous fables, Kheerer Putul.

One of his best known fables

One of his best known fables

This once-upon-a-time story of a king with two queens – the suffering elder Duorani and the pampered younger Suorani – and the change of fortunes that come about in their lives is an old tale of triumph of good over evil. But it is ironic in its fantasy where at the onset we know that “jewels and ornaments as vast as that of seven kingdoms taken together” filled the chests of Suorani. This is where Abanindranath Tagore incites the mind of a young reader to imagine beyond the possible – the contour of the eye stretches beyond the circumference of the face.

Or, take for instance, Suorani’s demand from the king who wishes to travel to countries far and wide (without his wives) – she asks him to bring for her bangles of ruby as red as blood, fiery-red anklets made of gold, necklace of pearls as large as pigeon’s eggs, and a sari blue as the sky, feathery as the wind and light as water. Now visualize all this with the awe of a child. And what does Duorani asks to bring – a black-faced monkey. A smile lights up your child-face. Unknowingly, the reader lets himself be led by the author into the amazing world of imagination with a willing suspension of belief.

Rajkahini by Abanindranath Tagore

Rajkahini by Abanindranath Tagore

Abanindranath explored various medium to express his creativity. The sensitive and innocent world of children always attracted him and inspired his imagination. During his advanced years, he began his playful series of miniature sculptures and named it ‘Katum Kutum.’ It all happened by chance. One day, Abanindranath noticed a branch of a felled tree lying in the garden. He was attracted by the shape of the branch and picked it up. He chipped away here and there and lo behold! A figure was etched out! Abanindranath was stimulated by this new medium and instantly got hooked to it. He began collecting fallen and discarded branches and twigs of trees then etched out an entire series from them.

As an artist Abanindranath started with naturalist approach. He wanted to comprehend nature with his art sensibilities and produce artifacts. He was inclined towards a poetic vision of reality, based on nature, but at the same time poetic in character. If we analyze all the Abanindranath’s work, spread over half a century of his working life, they will include various categories, some playful, some exploratory, some in the nature of recreational scribbles. Today, on his birth anniversary, we pay homage to an extraordinary genius. He will live on in the annals of outstanding international artists.