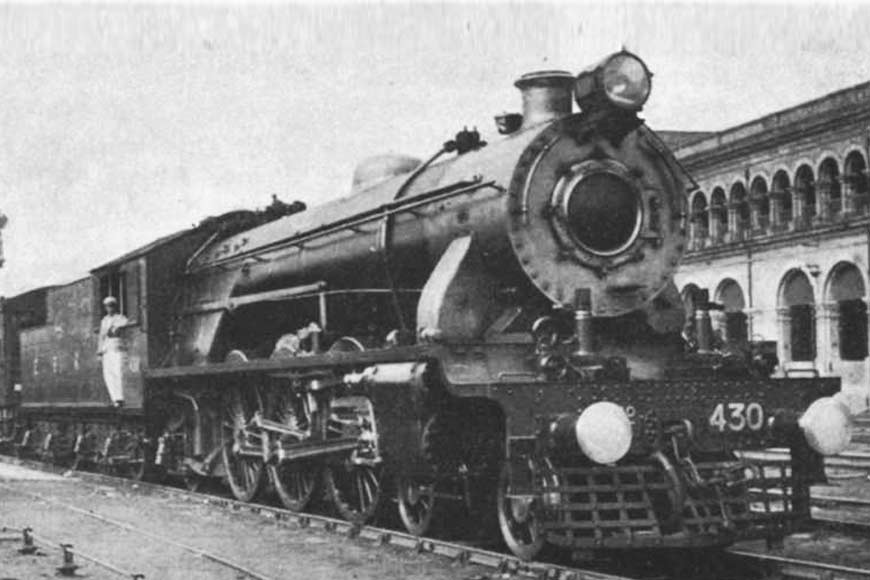

Chugging tales of Bengal Railways: Was Bengal’s Agricultural Decline related to Railways?

Part 4: Did laying of Railways lead to Bengal’s Agricultural Decline?

Historians have argued that one of the reasons for the Bengal Famine in 1943 was the stoppage of importation of rice from Burma during the Japanese occupation. But they have hardly enquired why, in the first instance, rice production declined in eastern Bengal. In this context, it might be assumed that the decline of the ecology led to a decline in both commercial and subsistence produce which, in combination with other factors, ultimately led to the famine. One needs to raise the question whether the railways with their long arms of embankments could partly be responsible.

The railways in Bengal in general expanded amidst overwhelming approval from investors in London and colonial officials and an emerging middle class in Calcutta. A positive perception of the railways was so wedded to the state-formation process that there was hardly any room for critical voices. An overt emphasis on the potential of the railway as a system and symbol of modernisation met with sharp reaction from those who were skeptical about modernity itself. Karl Marx hoped for an extensive irrigation system, emerging as a result of digging the soil for railway embankments, but he did not see the problem of drainage. On the other hand, Gandhi could well perceive the railways as carriers of fatal diseases like the plague, but he did not pay much attention to the capacity of the railways to create disease itself by destroying the environment.

Surprisingly, a scientific approach to the problem of embankment in the deltaic landscape of Bengal came from a segment of the colonial officialdom. In 1846, a committee appointed to examine the problem of embankments in Bengal put forward some strong arguments against any barrier in the fluvial and flat landscape. Comprised of two engineers and a botanist, the committee proposed a ‘return to that state of nature, which, in their opinion, ought never have been departed from.’ To achieve this goal, the committee recommended the total removal of all existing flood embankments to allow the free flow of water. The proposed system, to be built in consonance with ‘local experience,’ was tantamount to reversing the existing system of embankments by substituting them with drainage.

When CA Bentley, Director of Public Health, Bengal, reiterated his concern in the early twentieth century over the negative impact of the railway systems on the water regime of Bengal and on its ecology and agriculture, it was too late, for the railways had already become an integral part of public life.

(To be continued)

(Source: FIBIS Fact File #4: “Research sources for Indian Railways, 1845-1947”

'Researching ancestors in the UK records of Indian Railways'

India Office Records (IOR) held at the British Library)