Chittoprasad Bhattacharya, whose sketches on Bengal famine spoke a thousand words!

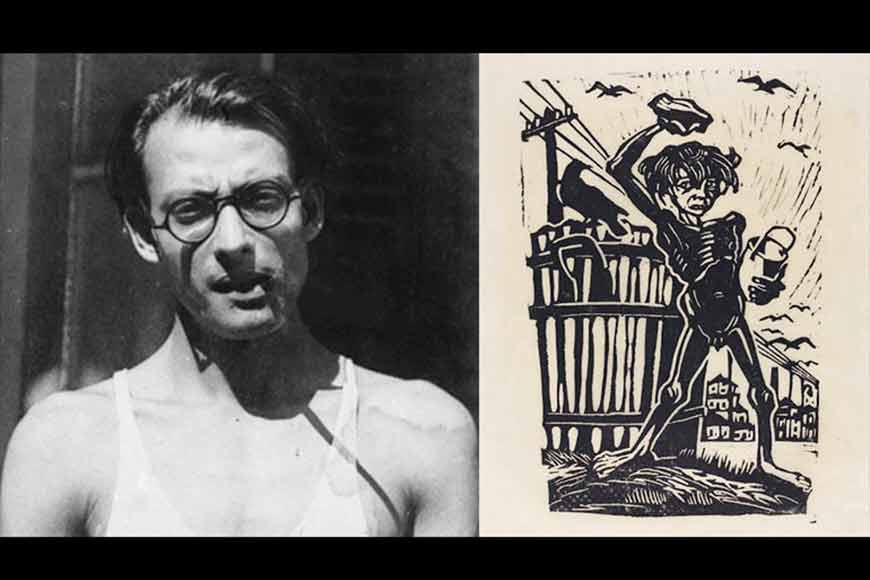

He was the quintessential ‘Everyman.’ With a crown full of unruffled, matted hair, the strap of a much-used, shabby cotton tote bag hanging from one side of his lean shoulder containing useful tools – his sketch books, pens, pencils and ink bottles and a very descript countenance, he would have passed off as any common man on the streets but for his sharp piercing eyes behind the foggy glasses which searched around relentlessly for the oppressed common man whose sufferings he depicted in quickly drawn but masterful pen and ink sketches. He was Chittoprasad Bhattacharya.

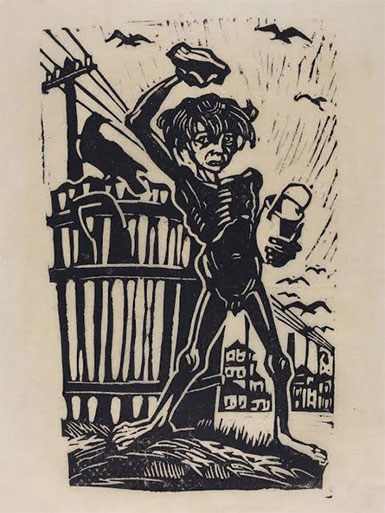

Chittaprosad studied at Chittagong which was at that time the main centre for revolutionaries fighting the oppressive British rule. He was a radical while studying at Chittagong Government College in the mid-1930s and joined the grassroots movement to resist both colonial oppression by the British and feudal oppression of the landed Indian gentry. He was a staunch activist and an active member of the Communist Party of India. In the 1940s, he was inspired by Purnendu Dastidar to join revolutionary activities and took shelter at the office of the Student Federation of India in Kolabagan. During this time, many of his anti-Fascist woodcut prints, sketches and cartoons were published in the party’s journal Jana-Yuddha aka ‘People’s War. Gradually, he became an important voice in the fight against colonialism and believed that art-making is inherently a political act.

In 1943 Bengal suffered one of the worst man-made famines in the world, that killed almost three million people — as a direct result of British World War II policies robbing Bengal of all its food grains, using them to feed British military and citizens. The Western Press was obsessed with news of World War II. The Communist Party of India (CPI) assigned Chittoprasad and photographer Sunil Janah to tour the famine-struck districts of Midnapore and Bikrampur and document the horrific human suffering.

In 1943 Bengal suffered one of the worst man-made famines in the world, that killed almost three million people — as a direct result of British World War II policies robbing Bengal of all its food grains, using them to feed British military and citizens. The Western Press was obsessed with news of World War II. The Communist Party of India (CPI) assigned Chittoprasad and photographer Sunil Janah to tour the famine-struck districts of Midnapore and Bikrampur and document the horrific human suffering.

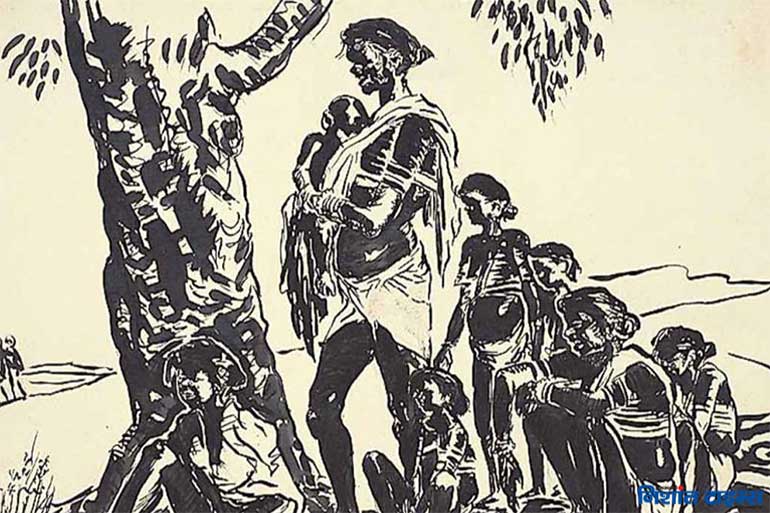

Like a man possessed, he travelled villages, his sketch books filled with series of pen and ink sketches portraying impoverished households, skeletal bodies of people starving, and pot-bellied sick children with sad faces and lanky bones. He witnessed famine, starvation, death, communal killings, ravages of war and Partition and documented them in his inimitable style, through art. Chittoprasad’s illustrated report/ sketchbook account of the famine was published in 1943, titled ‘Hungry Bengal.’ But the British government immediately seized and destroyed all.

Chittoprasad was a self-taught artist. He always wanted to pursue art but was denied entry into either Kala Bhavana of Santiniketan or even Government College of Art & Craft for his political leanings. A determined young man, he decided to shun the traditional path and charted his own language of art. Tempera paintings was prevalent at that time from the Bengal School of Art which focused on revealing India’s distinct spiritual qualities, and was often inspired by ancient murals and medieval imagery. Chittoprasad devised a straightforward, provocative style. His works reflect his reformist concerns. They are a depiction of the images that were his preoccupation --- poor peasants and labourers.

Produced during visits to villages, makeshift camps, hospitals and orphanages located in different parts of Midnapore, his spare black and white images are devoid of ornament or flourish, revealing a bleak landscape. He constantly experimented with the art of picture making and quickly adapted to the need of the times and switched to simpler lines and fewer exaggerations of forms.

A bulk of Chittoprasad’s works are in his black and white drawings prints and watercolors. His woodcuts, linocuts and posters are renowned for their brutally honest depiction of human suffering. They remind viewers more of contemporary graphic novels. The carved faces, barren trees and lined rib cages of his illustrations tell a story of inescapable scarcity and deprivation through strong, simple black strokes. The protagonists seem to tear the surface and come out of picture frames, communicating with the viewers. His hard-hitting caricatures and sketches of the poor dying during Bengal famine worked like modern day reportage and shook the middle class and even British officials.

In 1944, Chittoprasad traveled to other regions in Bengal, many of which are in present-day Bangladesh, where he chronicled the lasting effects of the famine. He also painted a series depicting the Naval Mutiny in Bombay (1946). And in the same year, shifted base to Bombay.

In his later years, he was hurt to see his party comrades get involved in squabbles leading to the disintegration of the party. He consciously stepped back from the party though his faith in the philosophy of social equality remained intact till the very end. Meanwhile, he continued to depict rustic life in his experimental woodcuts, prints and watercolor paintings. His works reveal his lifelong mission, best summed up by Chittoprasad himself in Czech filmmaker Pavel Hobl’s short documentary on him: “To save people means to save art itself. The activity of an artist means the active denial of death.”