Centenary for some, obscurity for others, the story of Bengal’s newspapers

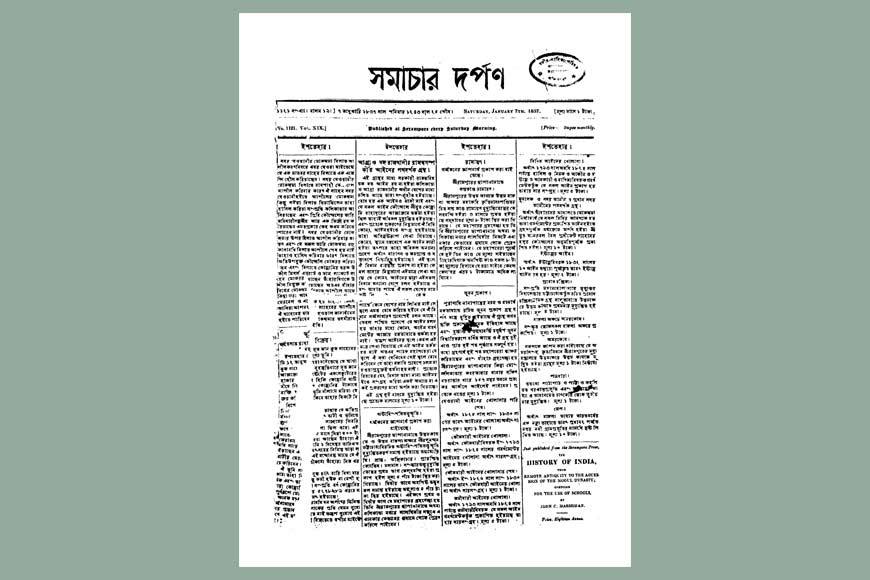

Front page of Samachar Darpan, January 7, 1837

The ongoing fanfare surrounding the centenary of leading Bengali daily Anandabazar Patrika, while no doubt justified, makes it easy to forget the pioneers who paved the way for Suresh Chandra Majumdar and Prafulla Kumar Sarkar to launch their evening daily on March 13, 1922. Indeed, the name Ananda Bazar itself was similar to a small newspaper which began to be published in 1868 in Jessore district (now in Bangladesh) by brothers Sisir Kumar and Motilal Ghosh. This humble publication, called Amrita Bazar Patrika, was to earn the family a fortune as the first Indian-owned English newspaper in the country, though it began life as a Bengali weekly.

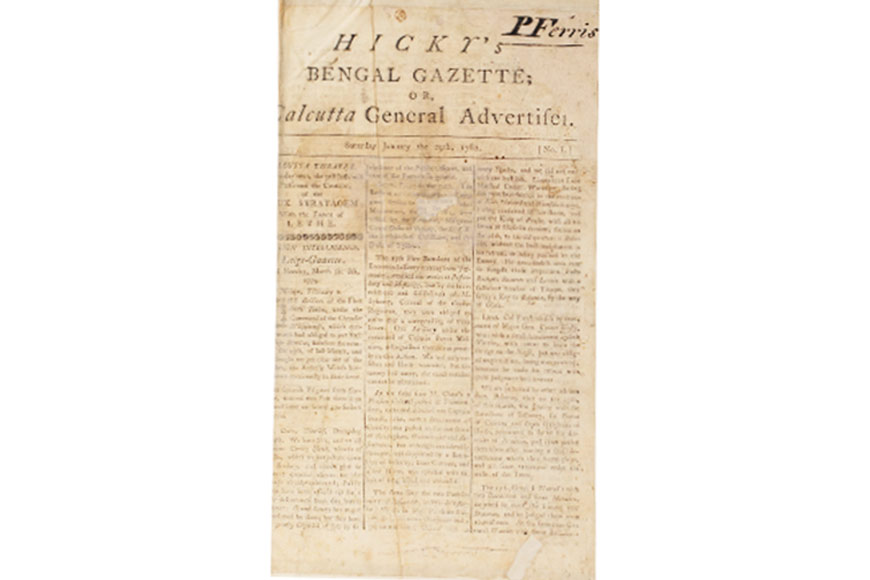

However, with Amrita Bazar Patrika controversially folding up in 1991 after 123 years of continuous publication, its centenaries have come and gone unnoticed. The same fate has befallen some of the country’s oldest newspapers published from Bengal, such as the once sensationally popular Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, the first newspaper printed in Asia, published for just two years between 1780 and 1782.

First page of first edition of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, January 29, 1780

First page of first edition of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, January 29, 1780

Its proprietor, the eccentric and free-spirited Irishman James Augustus Hicky, printed disparaging and delightfully accurate gossip about the esteemed European lords and ladies of Calcutta, and seemed to take special pleasure in baiting the administration of Governor-General Warren Hastings. To nobody’s surprise, the British East India Company soon seized his newspaper’s types and printing press, bringing one more of Hicky’s ventures to a premature end.

Possibly inspired by Hicky’s newspaper was the Bengal Gazetti, yet another publication whose story has been lost to the march of time. This Bengali weekly began life in 1816 or 1818, which is the closest we can get in the absence of any surviving copies. Some researchers have called it the first Bengali language newspaper, but the wider consensus seems to be that that honour goes to Samachar Darpan, another Bengali weekly published by the Baptist Missionary Society on May 23, 1818 from the Baptist Mission Press at Serampore.

In fact, Samachar Darpan is considered to be the first Indian-language newspaper, and Ganga Kishore Bhattacharya, the joint proprietor of Bengal Gazetti, was a former employee of the Mission Press. Unfortunately, his newspaper ran for only about a year, and whatever the dispute surrounding its chronology, what is certain is that it was the first newspaper in India controlled entirely by Indians.

Plaque in memory of Ganga Kishore Bhattacharya

Plaque in memory of Ganga Kishore Bhattacharya

Meanwhile, as is evident, the bicentenary for Samachar Darpan came and went four years ago. Happily, plenty of its reports are still available to us, and make for fascinating reading, painting a clear picture of both Indian and European society of the time. In December 1841, however, the missionaries decided to discontinue publication, the official reason being that editor John Clark Marshman could no longer make time for the paper.

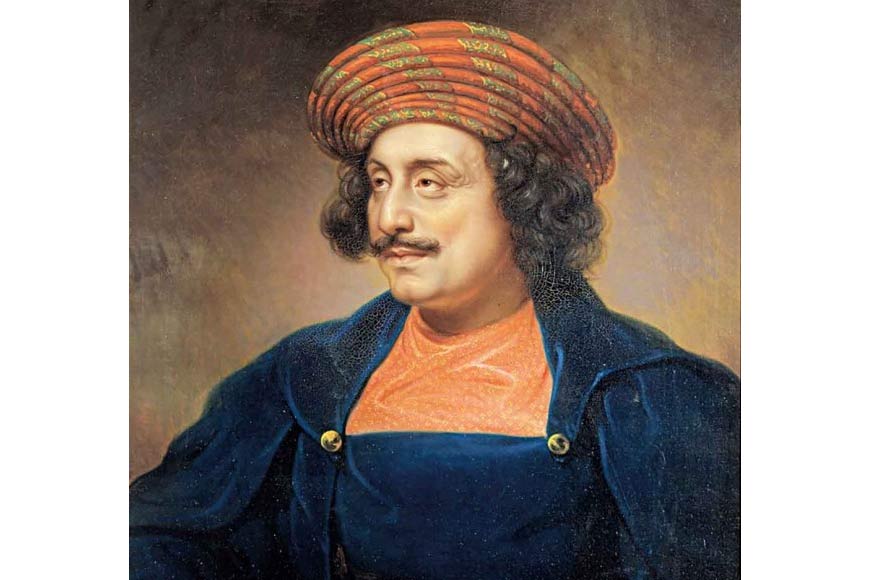

As became evident later, the actual reason was that Samachar Darpan, though highly successful commercially, had failed in its primary objective – the propagation of Christianity among the natives. In fact, the paper became involved in a bitter theological dispute with Raja Rammohan Roy, leading to the latter founding the short lived Brahmanical Magazine in 1821. And so, while it was briefly revived in 1842, Samachar Darpan quietly shut shop again just over a year later, this time for good.

Raja Ram Mohun Roy

Raja Ram Mohun Roy

Yet another contemporary publication, the Bengal Hurkaru (derived from the Persian ‘harkara’ or messenger), often published stern admonitions to the administration. In its edition dated May 12, 1829 for instance, the paper draws the attention of the authorities to a “disgraceful” lapse on the part of Calcutta Police in removing the body of an unfortunate man who apparently dropped dead near the southwest corner of Wellington Square on a Sunday, and yet his body had been left lying on the road until Tuesday, when the paper was being sent to press. Citing the decomposing corpse as an example of the police’s unpardonable indifference, the editorial emphasises how such an instance was probably unheard of in any other British-ruled nation.

The irony here is that Bengal Hurkaru was intended primarily for circulation among the British military, merchants, and civil workforce, though it did have a few Bengali subscribers. On September 24, 1842, it published a report of an appeal by residents about the general rowdiness of their neighbourhood. The report stated, “The application was for the interference of the Magistrates to check the constant din and uproar, at almost all hours of the night and day, in that vicinity, caused by sea-men and others, riotous characters, who frequent the numerous public houses with which Loll Bazaar and Bow Bazaar abound ....”

The irony of residents complaining about the rowdiness of Lalbazar, which was to house the headquarters of Calcutta Police, is indeed priceless. In similar vein, on June 1, 1843, a reader wrote in about a police complaint filed by residents of certain areas about the “public nuisance” caused by prostitutes who would line the streets in broad daylight, accosting passing men in “bawdy” language, dancing in public, and generally creating a scene, secure in the knowledge that their wealthy and powerful patrons would protect them from the law.

In an interesting exercise in August 1837, The Friend of India (founded in 1818, later to become The Statesman), published a list of newspapers with outstation readers to whom the paper would be sent by post. This was presumably intended to convey the comparative popularity of these publications. In a report about the exercise published in Samachar Chandrika, we learn that of the 42 newspapers being published in India at the time, 15 made it to the list, of which as many as seven were from Bengal.

Head and shoulders above the rest stood Samachar Darpan from Serampore with 137 outstation deliveries, and Darpan from Bombay a distant second with 61. The remaining six papers on the list all came from Calcutta - Ain Sikandar (Persian, 52 outstation), Sultanul Akhbar (Persian, 27), Jamjahanama (Persian, 22), Mane Alam Afroz (Persian, 15), Gyananweshan (Bengali and English, 11), and Samachar Chandrika (Bengali, 11).

The numbers seem paltry today, but considering the general standards of literacy in 1837, and the postal expenses involved, the numbers are not to be scoffed at. Unfortunately, as the Samachar Chandrika report pointed out, there was no way of ascertaining the total circulation of a publication, local and postal combined, though local circulation had to be many times the postal.

So these were the ground-breakers who showed the way. As we observe one centenary, it would perhaps be fitting to remember the many more we have simply pushed into the cold storage of history.