‘Burdwan stew’ and ‘loll shraub’, what the sahibs of old Calcutta ate and drank

For the men and women of the British Raj, India was often a land of exile, which offered them very little of the routine comforts they had been used to at home. However, they did their best to address the situation by substituting Western comfort with ‘Eastern splendour’. And since Calcutta was the centre of the British-Indian universe until the beginning of the 20th century, much of this splendour was on display in the city’s Anglo-Indian (in the original sense, that is, a mix of English and Indian) quarters.

How splendid was this lifestyle, actually? A now out of print old Anglo-Indian novel, called ‘The Baboo’, described the pomp and ceremony surrounding the domestic life of a high official and his wife in Calcutta, in the early years of the nineteenth century. Typically, the lady would descend from her room and pass to the breakfast table through a sort of domestic guard of honour, with an army of servants lining her path, bowing low as she passed. This army of servants remained an essential feature of Anglo-Indian life for more than a century, though their numbers went down as the world modernised itself.

A south-east view of Government House, Calcutta by James Moffat (1775-1815)

A south-east view of Government House, Calcutta by James Moffat (1775-1815)

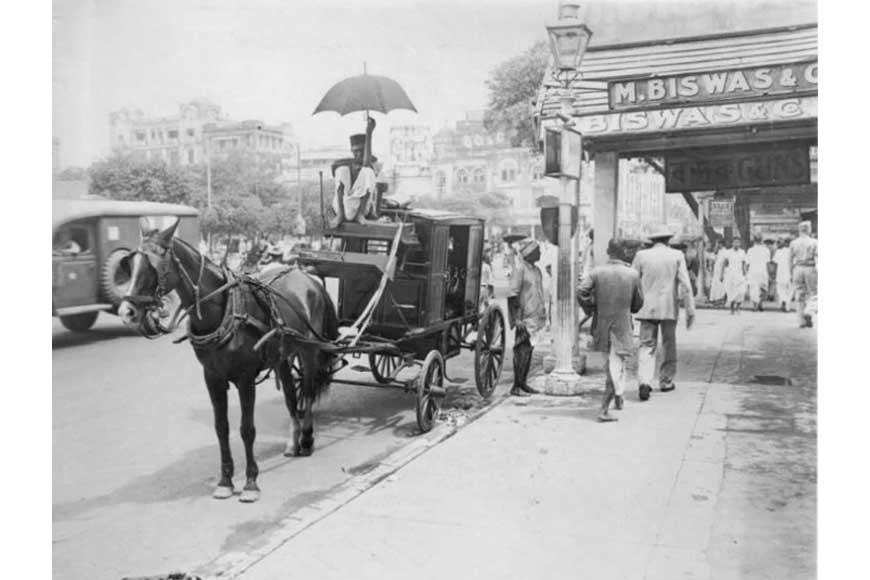

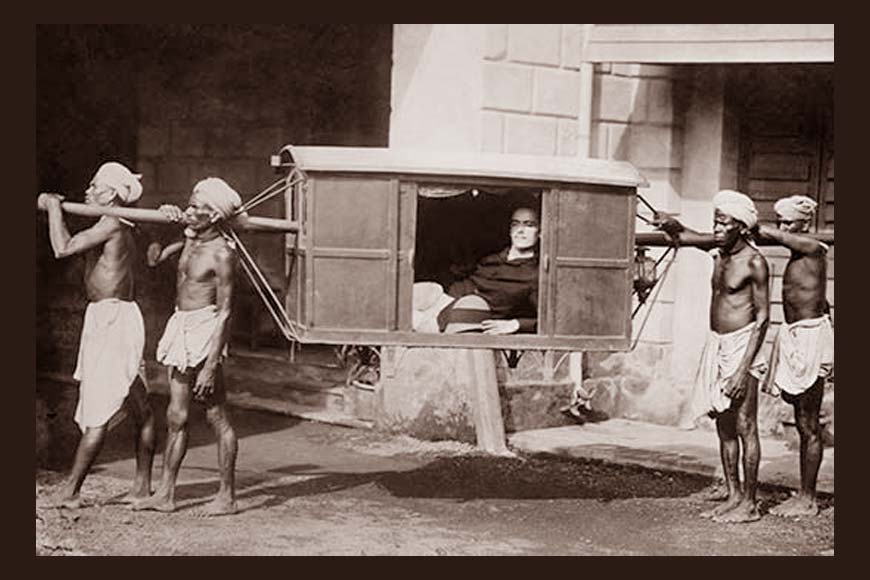

In 18th and 19th-century Calcutta, a reasonably well off English household would, at the very least, comprise table servants, bearers, a cook and his helpers, and such staff as a ‘chobdar’ or mace-bearer, a sort of senior footman whose duty it was to supervise the procession when his master went on a walk or rode in a palanquin. Even when carriages had replaced palanquins, the chobdar remained as an ornamental appendage, merely to add to a household’s prestige.

Then there were the ‘jemadar’ (jamadar, who in those days was a junior officer, not the sweeper we know today) and his assistants such as peons or ‘chupprassies’, who formed a guard; the ‘palkee’ bearers, who cost thirty rupees a month; the ‘mussalchees’ (masalchi or torch-bearers), who ran swiftly, “at the rate of full eight miles an hour”, carrying blazing torches before their masters’ carriages, to light them on their way. Human headlights, in other words.

Still other household staff were the barber, whose pay was a modest two to four rupees, and the hairdresser, who was evidently superior to the barber, being paid a salary of sixteen rupees a month; the ‘abdar’, who cooled the wines; the ‘hookabardar’, who had sole charge of the master’s and mistress’ hookah. The hookabardar was actually an artist, preparing the “rich, soft, brown mass of tobacco”, to which were added fragrant spices, treacle, and cool rosewater. So strict was the protocol that when the master dined out of home, among the servants accompanying him were his hookabardar bearing the precious hookah, the ‘khansamah’ who waited on him at table, and the bearer, carrying the mandatory white dinner jacket.

No less lavish were the quantities of food and wine which loaded the tables. In 1720, ‘the inhabitants of Calcutta’ enjoyed a variety of fruit and fish. Nearly 60 years later, a certain Mrs Fay, a notable Calcuttan, wrote about food supplies and prices in one of her letters: “I will give you our bill of fare, and the general prices of things: A soup, a roast fowl, curry and rice, a mutton pie, a forequarter of lamb, a rice pudding, tarts, very good cheese, fresh churned butter, fine bread, excellent Madeira (that is expensive, but eatables are very cheap). A whole sheep costs but two rupees, a lamb one rupee, six good fowls or ducks ditto, twelve pigeons ditto, twelve pounds of bread ditto, two pounds of butter ditto, and a joint of veal ditto.”

In another letter, Mrs Fay wrote of the highly spiced and seasoned dishes served at Calcutta tables, and particularly described ‘Burdwan stew’, a sort of ‘hot-pot’ in which “fish, flesh, and fowl combined with unlimited seasoning, the whole prepared in a silver saucepan, resulted in the most appetizing of dishes”. At this time, according to many chroniclers, dinner was at two o’clock, and supper at ten o’clock. Some years later, ‘evening dinners’ were introduced between seven and eight o’clock, but the midday meal was still retained under the name of ‘tiffin’.

“Calcutta dinners are languid sorts of things,” wrote a visitor in 1805. “You have the stomach perhaps to pick the bone of a floriken, or may get through a fine delicious snipe, but you cannot grapple with a slice of beef or of Bengal mutton. The tiffin, a meal at two o’clock, defrauds the dinner of its homage due. But the luxury of the first glass of cool claret (‘loll shraub’) that salutes your lips! Skilfully refrigerated, it is a celestial draught…”

‘Loll shraub’ was the anglicised distortion of ‘laal sharab’, which is what natives called the red claret. Claret was a firm favourite with the ‘sahibs’, though it had many rivals. But whatever the wine, it was essential it should be cold: this was done by the use of saltpetre and Glauber’s salts; and a special servant or ‘abdar’ was retained in every household, whose sole duty it was to keep the day’s supply of ‘drinks’ at the required temperature.

However, the difficulty and expense of importing European wines and brandy led to the consumption of the local spirit ‘arrack’, which was apparently the cause of an immense deal of drunkenness and mortality, especially among young writers (clerks) and soldiers. However, high officials were able to afford the high prices of wine, which varied according to the supply in the market, and it was usual “for a man to take three bottles of claret after dinner daily, besides the Madeira which he consumed during the meal, and for a lady to drink one bottle of wine a day”.

Another day, we will look at the lavish entertainments hosted by the British in Calcutta, where all the food and wine were put to good use.