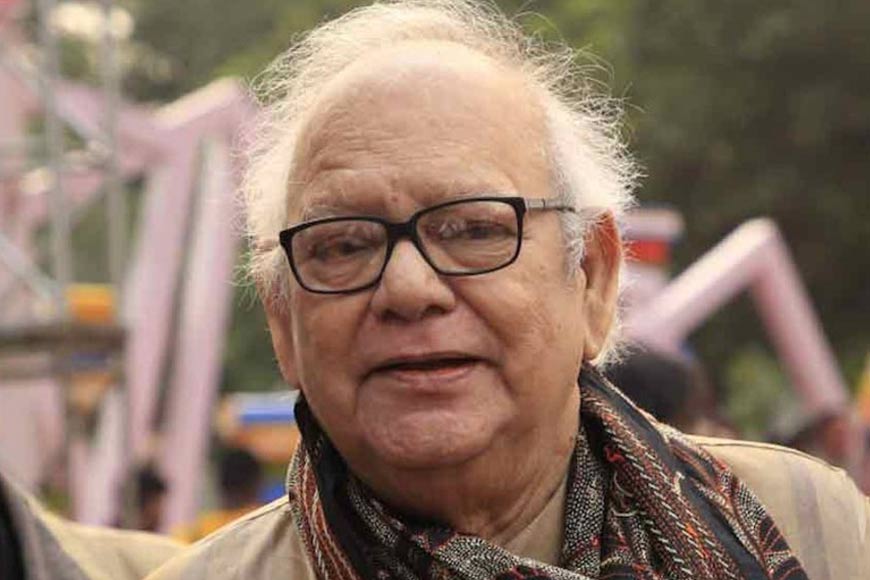

Buddhadeb Guha takes with him a nearly extinct world

Buddhadeb Guha - it still seems too early to call him the ‘late’ Buddhadeb Guha - inherited his love for nature and wildlife, as well as life in general, from his father Sachin Guha. The latter, a large, loud, prosperous, extremely generous man, would organise lavish hunting trips to the various forests of eastern India, where the focus was always on having a good time amidst nature’s bounties rather than necessarily hunting anything. I know this, because my father was part of many of those trips as a friend of ‘Lala’, as Buddhadeb was called at home.

Thanks to the time the two young men spent in the forests of Assam and North Bengal, my father, a thoroughly incompetent hunter who never so much as managed to kill a duck, featured in quite a few of Buddhadeb Guha’s writings. Their relationship continued well beyond their jungle safari days, with the result that every time Lala wrote a new book, my father would receive a complimentary copy. Which meant I developed a healthy relationship with the works of Buddhadeb Guha from early childhood.

As we deal with the news of his passing today at the age of 85 from Covid-related complications, I wonder whether we have really accurately assessed the many talents of a man most Bengalis are accustomed to think of simply as the creator of Rijuda and Ribhu. Even the Wikipedia entry for him mentions that he was a writer of ‘fiction in Bengali’. There is no mention of his tremendous gifts as a raconteur, his genuine abilities as a singer, his encyclopaedic knowledge of music and food, his various works of nonfiction such as ‘Banajyotsnay, Sabuj Andhakare’. All this, while managing a career as a successful chartered accountant.

Later in life, he also took a great interest in conservation and the environment, particularly the efforts to save the Royal Bengal Tiger. Anybody who has read his jungle stories - fiction or otherwise - would agree that he wrote of the forests with an eloquence and love that only true passion could bring forth. However, that is not to ignore his skills as a character sketch artist. Think back to his marvellous stories about the well-to-do, Westernised, aspirational, wannabe Bengali elite, people on the city’s Page 3 circuit before Page 3 was even a thing.

Every time we spoke in the past few years - and I regret to say that the number of conversations dwindled almost to nothing after the passing of my own father - talk would turn to the days of their youth, and he would tell me stories I already knew, but was glad to listen to again all the same. And he would invariably end with, “Ekdin esho, kotodin achhi to thik nei (Do drop in, who knows how long I have).” Once again, I regret to say that I never managed to take him up on his offer.

The death of Buddhadeb Guha has not merely robbed the world of Bengali literature of one of its last giants, but also impoverished us in other ways. He represented the nearly extinct world of the Bengali bhadralok, the highly educated, sophisticated, worldly, cultured Bengali - equally at ease tramping through Kaziranga or having tea at Buckingham Palace. A man who could enrich any conversation with the depth of his knowledge and the sheer joy of living.