Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee: Legacy of a conflicted ideologue - GetBengal story

“Outgoing West Bengal Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee lost to Trinamool Congress nominee Manish Gupta by 16,684 votes from Jadavpore constituency. Gupta polled 103,972 votes, compared to Bhattacharjee’s 87,288. Bhattacharjee has been winning from Jadavpore since 1987. This is the first time the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M) has lost Jadavpore since the seat was carved out in 1967.”

Thus began an agency news report dated May 13, 2011, widely published on numerous media platforms. And one had no way of knowing it then, but the flat, dry prose of this report was actually an epitaph for West Bengal’s longest-serving government, the Left Front. The decline that two-time Chief Minister Bhattacharjee’s defeat spearheaded has been in free fall ever since.

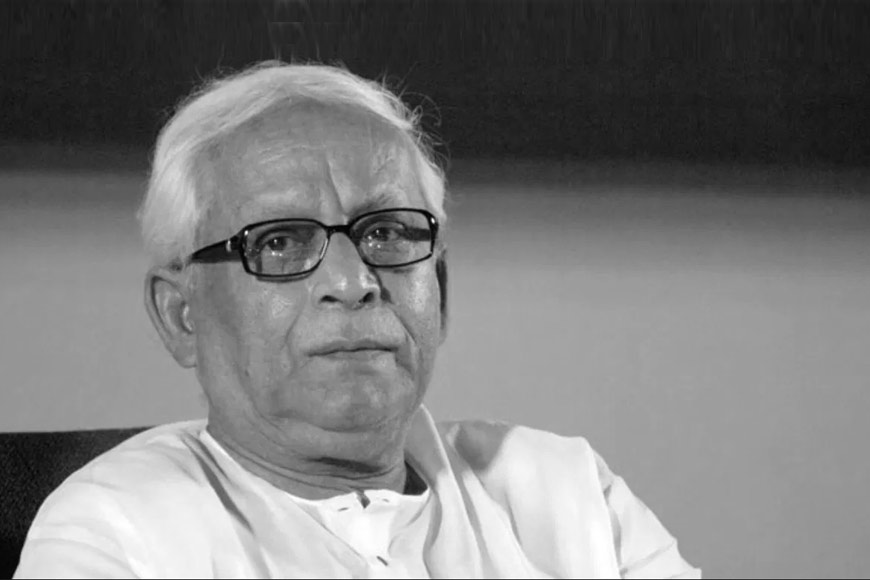

Sadly, that decline is also likely to be his preeminent legacy. Whatever else he is remembered for, Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, who passed away in Kolkata today aged 80 from age-related and respiratory complications, will always be the man who presided over the funeral rites of the Left Front in Bengal.

For a leader of his vision and intelligence, handpicked by late CPI(M) supremo Jyoti Basu as his successor, this does seem tragically unfair, yet curiously justified. Bhattacharjee’s failure to resolve the dichotomy between his party’s ideology and his own desire to push for industrialisation (and by extension, state-sponsored capitalism) was to prove his undoing. His inability to gauge either the popular sentiment or that of his own party colleagues led him to squander in his second term all the goodwill he had earned in his first.

In 2006, as Bengal readied for Assembly elections at the end of Bhattacharjee’s first stint as Chief Minister, he clearly could do no wrong, at least as far as captains of industry were concerned. His energetic wooing of corporate India had led many business heads to rank him among the country’s best chief ministers, and sent investor interest in West Bengal soaring. Not bad for a state which had become notorious for the labour trouble and industrial ‘lockouts’ of the 1980s and 90s, leading to stagnant industrial growth. In a now famous comment, then Infosys finance director T.V. Mohandas Pai had said, “India’s renaissance in the 21st century will come from Calcutta, like it did in the 19th century.”

Two years earlier, in 2004, India’s then richest man and Wipro chairman Azim Premji had declared Bhattacharjee the country’s best Chief Minister, though crucially, the IT baron had also indicated that Bhattacharjee’s colleagues in Delhi and Bengal were yet to catch up with him. It was this that led Premji to place Bengal’s Chief Minister slightly ahead of former Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister and IT poster boy Chandrababu Naidu, because “he has many straitjackets around him”.

In his first five-year term, aided by his own unimpeachably honest image, Bhattacharjee coined the catchphrase “do it now”, as Bengal saw the development of several industries in general, and IT services in particular. In 2003, the government formulated a new IT Policy, and the sector underwent an astonishing 70 percent growth between 2001 and 2005.

Not surprisingly, the Left Front swept the 2006 elections, winning 235 seats against the 199 it won in 2001. It was an overwhelming mandate, and ought to have been Bhattacharjee’s true legacy. Instead, in the space of just five years, at the end of the 2011 elections, the Left Front had just 60-odd seats, which had halved by 2016, and come down to a resounding zero in 2021. An incredible journey for a coalition that had seemed invincible during the 34 years that it spent in power.

Meeting the press in 2006, Bhattacharjee made a comment that would come back to haunt him: “According to classical Marxism, there is a fundamental feud between capital and labour. But here we are practising policies of capitalism, not socialism. We do not want to raise slogans like ‘lorai lorai lorai chai’ (‘we want to fight, fight, fight’, a slogan popularised by Bengal’s Communists in the 1960s and 70s) and close down factories.”

Clearly, he was challenging one of the cornerstones of Leftist ideology, the sacred idea of the workers’ revolt that vanquishes the greedy capitalist. His party did not take it well, needless to say. Many of his comrades saw his approach as an attempt at self-aggrandisement, a betrayal of the cause by a man high on success, arrogantly making policy decisions without taking his party into confidence. That Bhattacharjee was equally out of touch with the proletariat became apparent as the state government attempted to push through a special economic zone (SEZ) at Nandigram and a Tata Motors plant at Singur, two locations that combined to form the Left Front’s Waterloo.

In Nandigram, a citizens’ protest against the acquisition of land for the SEZ spiralled out of control on March 14, 2007 when police opened fire on the protesters. According to official figures, at least 14 people were killed in the firing. The standout comment by Bhattacharjee about the incident was, “We have paid them back in their own coin.” This stunningly unfeeling reaction became fodder for political opponents as well as party colleagues.

Nandigram was closely followed by Singur, where the colonial era Land Acquisition Act became the Left Front’s weapon for a heavy handed takeover attempt of 997 acres of multi-crop land for the Tata Motors factory. This was highly fertile agricultural land, and Singur block as a whole is among the most highly fertile areas in West Bengal. Which meant the local population relied heavily on agriculture, with some 15,000 livelihoods directly dependent on it.

Since only about 1,000 jobs were expected to be created by the new plant, and not all of them would go to locals, it came as no surprise that local residents felt threatened by the development. Questions were also raised about whether the government was violating certain provisions of the Land Acquisition Act by using privately held land not for public purposes but to develop a private business. In fact, the legality of the acquisition was substantially questioned by the Calcutta High Court.

Once again, Bhattacharjee’s government chose to force the issue rather than tread a middle path. This was to prove fatal, because joining the local resistance movement was Trinamool Congress chief Mamata Banerjee, who successfully amplified the movement to a point where it began drawing not just national, but global attention. On October 3, 2008, Tata Motors announced that they were moving the project to Gujarat.

The countdown had begun. Three years later, the 2011 Assembly elections saw Trinamool Congress sweep to power with 184 seats, while the CPI(M) managed only 40, where even the moribund Congress party won 42.

Four years later, after five decades of service, Bhattacharjee was relieved of all key party responsibilities in 2015. The man who first became an MLA in 1977 from Cossipore apparently had nothing more to offer to either his party or his state.

The last decade of his life saw Bhattacharjee gradually withdraw from the public domain to live as a recluse. Deeply hurt by what he saw as a betrayal by his party, he reportedly refused to accept any help from his erstwhile comrades, not even money to pay for surgery for his rapidly failing eyesight.

Scrupulously honest and spartan to the end, his attempt to move out of his tiny government accommodation in Palm Avenue and live in a rented home was stalled by present Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, who arranged for him to continue living where he has done for decades. In a country where political corruption is the norm, Bhattacharjee has left neither property nor money behind for wife Mira and daughter Suchetana, who recently expressed a wish to be addressed as the masculine Suchetan.

Palm Avenue residents remember a quiet, dignified, unfailingly polite man who, as Chief Minister, would never allow his large security convoy to accompany him into the neighbourhood so as not to disturb his neighbours.

So while his legacy may be a troubled one, perhaps there is some room there for his other qualities – honesty, commitment, and unquestionable devotion to both his party and his state.