British Kolkata’s drainage blueprint: Did it flood back then?

After the sweltering heat of summer, monsoon is welcomed as a soothing balm and a harbinger of new life everywhere but it is red herrings for most residents of Kolkata who shudder at the very prospect of an incessant downpour for a couple of hours. Their panic and concerns are justifiable though. The capital of West Bengal plunges into depression literally every time there is heavy rainfall. Severe water logging causes total disruption of traffic movement in the city. Most ancillary services are affected due to flooding and many low-lying areas remain inundated for days in the end.

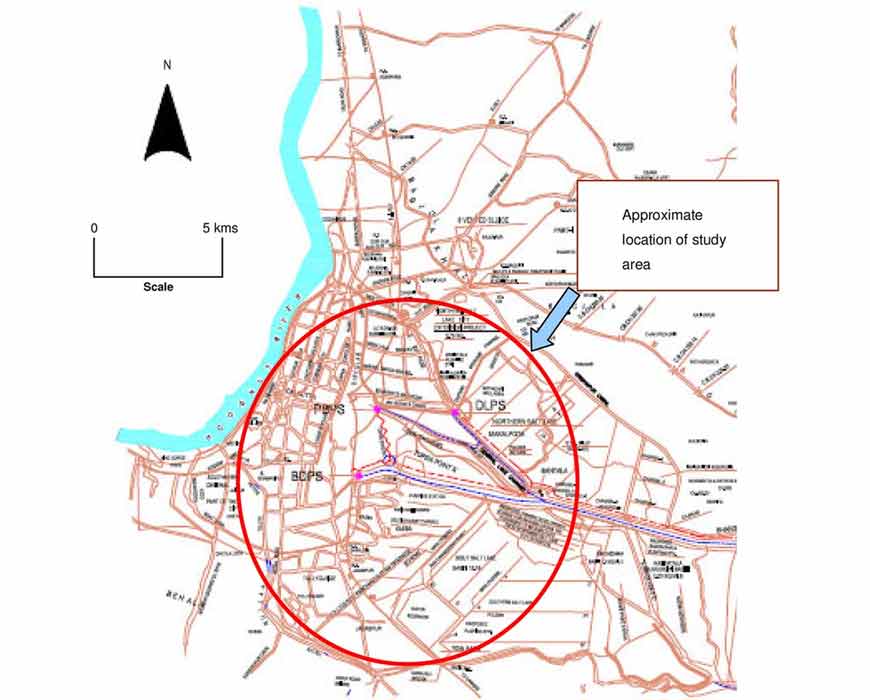

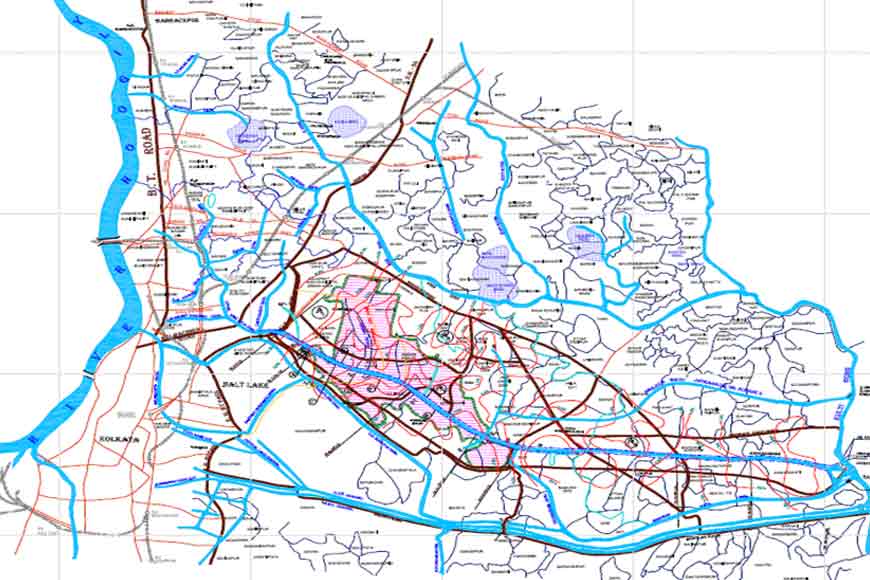

The crux of the problem lies with the city’s topographical location. Kolkata spreads linearly along the banks of the Hooghly River. Located near sea level, its average elevation is 17 feet. Most of the city was originally marshy wetlands, remnants of which can still be found especially towards the eastern parts of the city. Kolkata’s tryst with water logging goes back to the times when Kolkata as we know it now, used to be a collection of fishing hamlets interspersed with marshy lands, forests, creeks, and canals that connected the Hooghly River on the west with the Salt Lakes on the east. These creeks and canals served as the natural drainage system for both rainwater and sewage, which were carried east following the natural incline of the land and deposited in the Salt Lakes. The tides carried away the excess rainwater and sewage to the sea. Apart from the creeks and canals, a large number of tanks in each hamlet collected and stored the excess rainwater, preventing large-scale flooding in the area.

Yet, the densely populated areas on the river bank — especially the markets of Barabazar and along the old pilgrims’ way in Chitpore — did get flooded occasionally during a heavy downpours. The settlement around the Great Tank (now central Kolkata) would also be underwater during bouts of heavy rains. These areas were naturally the breeding ground of infectious germs and infested with malaria and cholera.

The problem of frequent water logging during monsoons increased after the British East India Company started developing Calcutta as a Presidency city in 1699. In 1715, the British completed building the Old Fort and in 1717, the Mughal Emperor, Farrukhsiyar granted the company the right to free trading in lieu of a yearly payment of Rs. 3,000. After the decisive victory at Plassey in 1757, East India Company consolidated its position and rapid and unplanned growth of the city started. As the developmental activities burgeoned in the 18th century, many tanks and creeks were filled in. Calcutta grew rapidly in the 19th century to become the second most important city of the British Indian Empire after London. But by now, the closure of natural drainage routes compounded the problem and water logging became a major cause of concern for the British. Apart from the distress it posed, water logging led to the unchecked spread of water-borne epidemics including cholera, dysentery, and malaria. The issue reached alarming heights forcing the small and cash-strapped Calcutta Government to take emergency measures. Several rudimentary narrow sewers were dug to drain sewage and rainwater to the Hooghly River, but the plan was faulty as the flow was against the natural eastward slope of the city, and it led to more stagnation of filth and rainwater during the monsoon. The ill-conceived plan was knottier and complicated the problem further.

In 1803, Lord Wellesley, the then-Governor General of British India published detailed minutes condemning the sad state of municipal affairs in Calcutta. In the report, Wellesley especially condemned the poor condition of drinking water, extremely unhealthy sanitation, and faulty drainage system in the city.

“The construction of the Public Drains and the Water-Courses of the Town is extremely defective, neither answer the purpose of cleansing the Town, nor of discharging the inundations occasioned by the rise of the River, or by the excessive fall of rain during the South-West Monsoon… Experience has manifested that during the rainy season, when the River has attained its utmost height, the present drains become useless; at that season the rain continues to stagnate for many weeks in many parts of the Town, and the result necessarily endangers the lives of all Europeans residing in the Town and greatly affects our native subjects.”

This report led to the formal appointment of Justices of Peace, early municipal officers, and the formation of an Improvement Committee in 1809 to look into the issues of sanitation, water logging, waste disposal, and health in Calcutta.

After Lord Wellesley left India, a Lottery Committee was formed in 1817 for town planning with the help of the government. The committee was set up with the funds raised through public lotteries and the money was utilized for constructing and doing up different parts of the city. The Committee commissioned a new city map of Calcutta to get a comprehensive picture of the city. The other major projects undertaken by the Committee were road building in the Indian part of the city, clearing of the river banks from encroachments, and constructing a proper drainage system.

Because of the lack of an underground storm water drainage network, large volumes of tidal water coming through the canal (from both the river and the Salt Lakes) during the monsoon would fill the open drains and compound the existing problem of water logging in the northern part of the city. Besides, several parts of the city lacked proper outlets for sewage and rainwater. After several intense brainstorming sessions, the only solution that seemed effective to handle Calcutta’s water logging and sewage problems was to construct an elaborate underground drainage network, including large storm water drains.

Three proposals were mooted for debate in 1835. The first, which was ultimately adopted, was from Major General (then-Captain) Forbes of the Royal Engineers. He proposed the construction of a masonry aqueduct from Chitpore to South Park Street Cemetery and beyond to the Salt Lakes. This canal, parallel to the Circular Canal, would be provided with sluice gates to admit tidal water from Hooghly and the Salt Lakes. The canal would be flanked by two large covered drains, to which all of the open drains of the city would be connected. These covered drains would, in turn, drain into the masonry canal. The covered drains and all other drains in the city would be flushed by admitting tidal water through additional sluice gates located in different places. The excess rainwater could also be drained into the canal. The canal, Forbes proposed, could also be used by small dinghies (boats) to transport goods against a toll. The water of the canal could also be used to hose down roads and extinguish fires.

The then-Superintendent of Roads of Calcutta, Mr. Blechynden, put forward the second idea. He suggested the construction of a large underground brickwork tunnel running from west to east, from the Hooghly to the Circular Canal near Beliaghata through Nimtala and Maniktala in North Calcutta. Smaller drains would deposit the sewage and excess rainwater into this underground tunnel, and the tunnel would be flushed by the tidal water from the river.

A third and more ambitious plan was proposed by Captain Thomson, an engineer and the Officer-in-Charge of Canals who suggested the construction of a large underground network of drains and storm water tunnels to be flushed towards the Salt Lakes by river water, which would be admitted through the Circular Canal and sluice gates at other inlets. James Prinsep, the famous antiquarian and orientalist scholar and an important member of the review committee, vehemently opposed the concept of an underground drainage system and was the only one to reject all three proposals outright. Although Forbes’ proposal was accepted but the plan had to be stalled due to a lack of sufficient government funds.

Finally, William Clark, an inventor and civil engineer, expanded on Major General Forbes’ proposal and submitted his plan to the Calcutta Municipality review committee in 1855. Clark proposed the construction of three underground main sewers connecting the Hooghly in the west and the Circular Road in the east. These canals would run under Nimtala Ghat Street, Kolutola Street, and Dharmatala Street. These main sewers would be intercepted by a north-south-oriented sewer from Sovabazar along the Upper Circular Road near Dharmatala. A sewer from the south would meet the north-south sewer and the Dharmatala east-west sewer along the Lower Circular Road from Tolly’s Nullah. All open drains in the city first flowed into one of these sewers and then ultimately emptied into one of four storm water overflows, which had larger capacities than all the intercepting sewers combined, to allow the drainage of excess rainwater during the monsoon. The storm water overflows carried the sewage (and rainwater) to the Circular Canal at Beliaghata, where a sewage pumping station was located at Palmer’s Bridge. The sewage was then pumped and drained out to Tangra Creek (now the neighbourhood of Science City) on the Salt Lakes. The mechanism continues to this day.

This scheme was approved by the committee in 1857. Between 1858–1859 the Government Drainage Committee took detailed measurements of the inclines in different parts of the city. Careful readings of the tides were made at Chitpore, Tolly’s Nullah, and Chandpal Ghat on the Hooghly and at Bamungahata, Tangra, and Dhapa on the Salt Lakes. Additionally, a large brickfield was acquired and brick-making machinery was imported from England. The cash-strapped scheme had to be halted several times. Besides, the rapid expansion and urbanization of the city and the growth of population compelled the authorities to undertake multiple modifications of the original plan which increased costs. Ultimately, in the late 1890s, Clarke’s Scheme was fully implemented and forms the skeleton of the current sewage and storm water drainage system in Kolkata.

(Data Source: The Shaping of Modern Calcutta: The Lottery Committee Years by Ranabir Ray Choudhury)