Black, White, and South: The many faces of Calcutta

Many of you may be familiar with the Bengali term ‘mutsuddi’, or know someone whose last name is Mutsuddi. The word comes from the Persian ‘mutasaddi’, meaning scribe or secretary, and was used to describe the local commercial agents of the British East India Company who went on to make fortunes from their work in the 18th and 19th centuries.

This community of people was among the original inhabitants of what the British called ‘Black Town’ - corresponding to the neighbourhood of Sutanuti and its surroundings, occupying nearly 80 percent of available land space in the growing city. They were among the wealthiest natives then living in Calcutta, and their mansions were scattered all over what we know as North Kolkata.

No matter what their social or financial standing, however, they were residents of ‘Black Town’ and as such, unworthy of British regard. Contemporary writings make it clear that the ‘white man’ was keenly aware of the source of native wealth, and determined to remind everyone of the fact.

In his book Notes on the Medical Topography of Calcutta (1837) Sir James Martin quotes William Hamilton as saying: “The great Native families, who now contribute to the splendour of Calcutta, are of very recent origin. Indeed, scarcely ten could be named who possessed wealth before the rise of the English power, it having been accumulated under our sovereignty, chiefly in our service, and entirely through our protection.”

Also read : Kolkata was once called 'Black Town'

What Hamilton probably ignored was the fact that some of these ‘great Native families’ were born out of prosperous families from the districts, descendants of zamindars and other landed aristocracy, who had made their fortunes under the Mughals and the Nawabs. Yes, like others, they were newcomers to ‘Calcutta’, but many of their ancestors had been living in Sutanuti, Gobindapur, and Kalikata – the three foundational villages from which Calcutta emerged – long before the British even thought of a settlement in these parts.

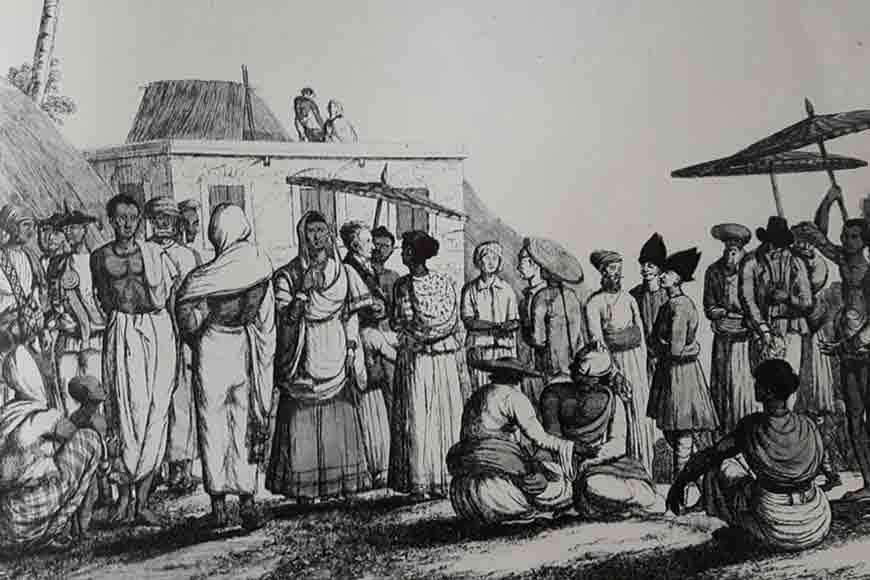

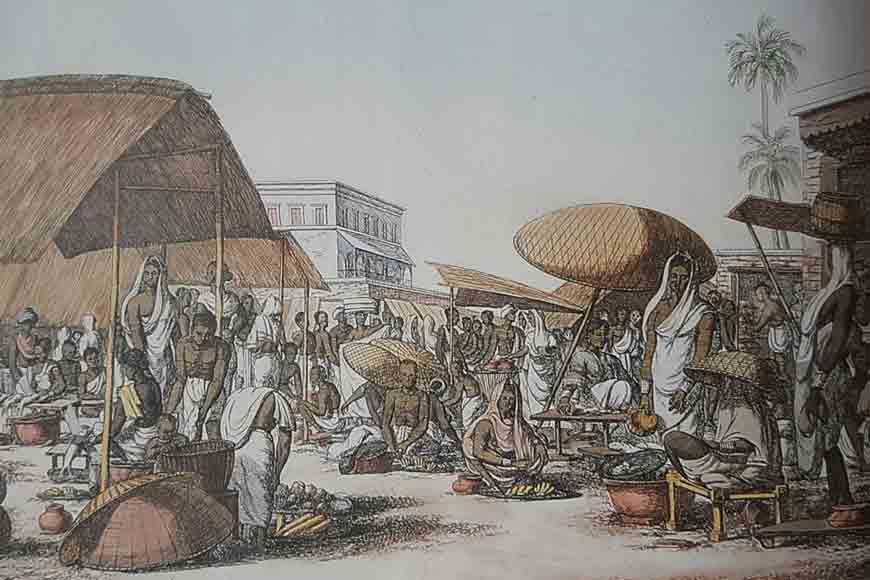

Anyhow, black and white did not cohabit well. The Black Town was not merely home to wealthy East India Company agents, but also a seething mass of impoverished humanity - the labourers, menial workers, and so called lower castes such as potters and fishermen - whose squalid humble dwellings were almost identical to the kind they had left behind in their villages.

Indeed, Black Town was entirely devoid of any urban planning, particularly in the poorer quarters, with houses piling on to each other, shops and marketplaces encroaching upon residential areas, narrow lanes and bylanes making their way between houses, and wide roads and thoroughfares conspicuous by their absence. If you think about it, many of these characteristics are still an intrinsic part of modern North Kolkata.

Residents of the Black Town did not mingle comfortably with those of the White Town - the central part of the city occupied predominantly by white-skinned Europeans, mostly British. Initially, the white people stuck to the areas around Esplanade and Park Street, having moved away from Sutanuti fairly soon after Siraj-ud-Daulah’s attack on Calcutta in 1756-57.

Instead, they now gathered in the village formerly known as Gobindapur, where the new Fort William was coming up. But Gobindapur was not spacious enough to accommodate the growing numbers of British and European residents flowing into the city – ranging from high-ranking Company officials to fortune hunters lured by stories of Bengal’s immense wealth and resources.

Soon enough, thanks to a grant from Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar giving the British the right to buy 38 more villages in and around Calcutta, the White Town had also come to encompass villages such as Chowringhee and Birji, south-east of the Esplanade area. The White Town was a stark contrast to the native settlements, complete with colonial mansions, wide roads, and plenty of open spaces including the Maidan, created along the lines of London’s Hyde Park by clearing the dense forests which occupied it.

By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the barriers between the Black and White Town had all but disappeared. A rising class of wealthy, confident Western-educated Bengali entrepreneurs and professionals had begun to move into the White Town, such as Theatre Road and its vicinity. In the early years of the 20th century, they began to move still further to the southernmost parts of the city, which were still semi-rural and densely forested.

And thus was born South Town and the term ‘south Calcuttan’, indicating a new community of upper class Bengalis who were rooted in their own culture while imbibing the Western influences they had acquired through their education. A typical example of this would be the descendants of the Tagore family of Jorasanko, very much part of the Black Town. In 1898, Rabindranath’s elder brother Satyendranath Tagore, a civil servant, bought property in an area behind modern day Gariahat Road, and moved out of the family home to his new house here.

This southward shift naturally led to greater urbanisation, and in 1929, these Bengali middle-class residents petitioned the Calcutta Improvement Trust to design a plan for the Ballygunge and Dhakuria Lake areas, on the grounds that there was a need for more building sites, improved communication and traffic facilities, and better roads. This led to the development of South Kolkata in a manner radically different from the northern parts of the city, a difference which remains evident even today, to the extent that it is easy for an outsider to assume that the two are actually different cities!

So there you have it - Black, White, and South towns in a nutshell. We would like to discuss each of these in detail in a series of forthcoming articles, so watch this space.