Bengal’s ‘Muluk Chalo’ stir was a harbinger of the trade union movement in India

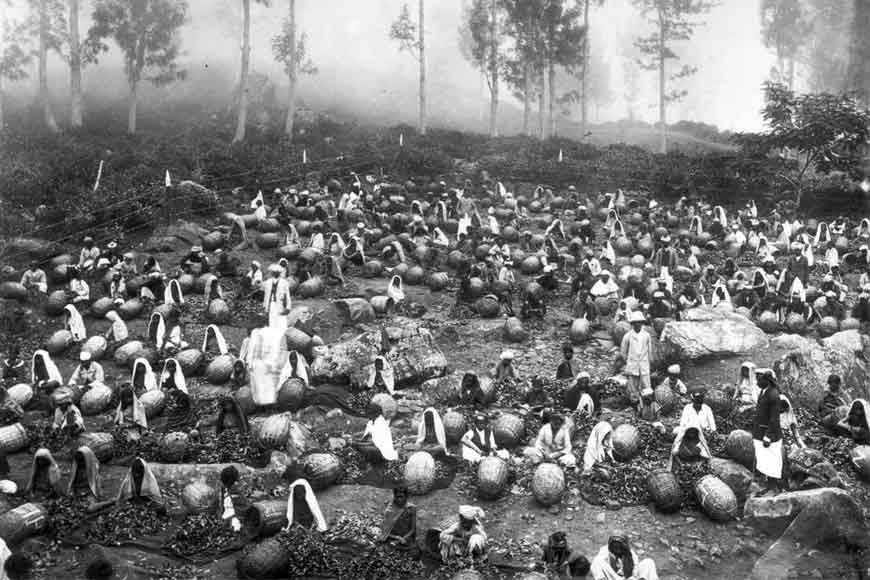

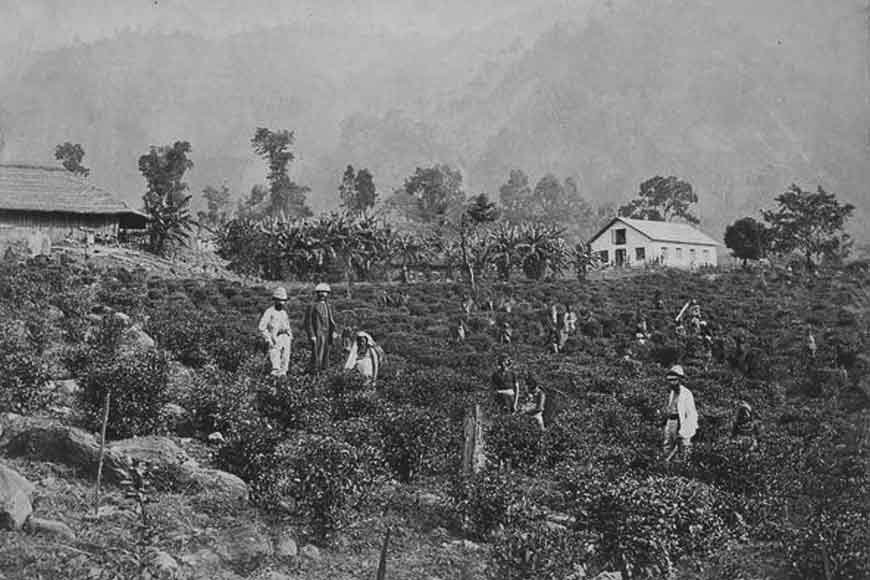

Colonization and free market had altered the socio-ecological set-up of colonies as imperialist countries began to control the inhabitants and the natural resources of the Bengal Presidency. The plantations of Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri became the seat of such exploitations. Most of the workers in tea plantations were riddled with poverty and compelled to migrate from Bihar, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. The European planters preferred to recruit labourers from other parts of the country as it enabled them to gain more profit at the cost of cheap wages.

Though in 1833, slavery was banned in the British Empire, the sly men at the East India Company needed to find an alternative -- and they did. Instead of slaves, tea estates used indentured labourers, free men, and women who signed contracts binding them to work for a certain period. In reality, once the workers signed and joined, their conditions weren’t any better than slaves. British traders introduced the system of recruitment of workmen through agents and a contract system. The plantation owners followed a stratified wage system among hired hands by which female and child workers were the worst victims. The workers were compelled to live in unhygienic and inhuman conditions that often resulted in a widespread epidemic in the slums. Most were illiterate so it was easy to dupe them and make them sign life-long contracts. Without ever committing any kind of crimes, they were forced to live in ghettos like prisoners and their lives were controlled by the owners. Oppression within the tea plantations was so great that workers often deserted their jobs but it was difficult to escape the prying eyes of their employers. Once caught, they would be subjected to extreme torture.

But 1919 was a year of changes. And that change started from the Bengal Presidency which had parts of Assam included. In March 1919, the British introduced the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919. Popularly known as the Rowlatt Act, it gave the police ‘extraordinary powers’ and allowed for ‘emergency measures’ to deal with people who were seen as threats to national security. The rights of Indians were violated as police and the army arrested Indians and confiscated their assets at random. The immediate fallout of the act was Satyagraha called by Mahatma Gandhi. The brutal torture meted out by the British planters finally culminated in a labor uprise in the Chargola and Longai valleys of the then-Karimganj sub-division in Sylhet district in 1921. Almost 9,000 besieged workers decided to leave their respective tea gardens en-masse to go back to their villages (‘Mulk’or native village) in North India. The mass exodus of tea garden workers known as the ‘Chargola Exodus’, created a huge political stir for nearly three months from May 3 to August 3, 1921, in Assam and Bengal.

Tea garden owners then resorted to other means to suppress the rebellion. They sought the help of public transport agencies and an indefinite strike was called by the railways and waterways transport. All modes of communication came to a grinding halt and the workers got stranded on their way.

Sushil Kumar Singh was the administrator of the Chandpur sub-division of the then East Bengal. Initially, he was sympathetic towards the workers but a couple of days later, the situation changed when McPherson appeared as a representative of the tea garden authorities. On May 19, armed soldiers, led by Singh, pounced on defenseless workers when they were boarding a ship. The pier or dock-way leading to the ship was suddenly removed from under the feet of the travelers. As a result, hundreds of children, women, and elderly people fell into the turbulent Meghna River and were washed away.

Meanwhile, the number of workers swelled at Chandpur station as they were determined to board the train and leave for their ‘Mulk.’ But the British administration had nefarious plans to crush the rebellion. Large police contingents, comprising mostly Gurkha men in mufti were deployed to surround the area. All railway personnel was ordered to vacate the station. Late at night, when the coolies were fast asleep, armed policemen entered the station and gunned down sleeping men, women, and children indiscriminately and fiercely chased out the coolies from the station yard. Many were drowned in the river and killed. Hundreds of corpses floated on the Meghna River. Those who survived the attack were forcibly taken back to the tea gardens and subjected to inhuman torture.

The workers’ cause was supported by members of the Assam Bengal Railway workers' Union, who called for a strike to protest against the massacre. Deshapriya Jatindramohan Sengupta was the president of the Railway Employees Union at that time. The Union went on strike for two-and-a-half months from May 24. The railway factory stopped functioning due to the strike and the economy of the region was virtually paralyzed. The British government controlled the situation with an iron hand. Section 144 was imposed and all railway employees posted at Chittagong were ordered to vacate the workers' quarters. Around 5,000 railway employees were laid off for supporting the ‘insurgents.’ The ‘Muluk Chalo’ aka ‘Chargola Exodus’ movement exposed the brutal exploitive character of the European planters and brought about a political consciousness all over the country. It also gave impetus to the trade union movement in India.