Bengal's Folk Rice: Conserving a Neglected Treasure

Once upon a time Bengal had more than 5,000 region-specific, indigenous varieties of rice, and the erstwhile Province of Bengal had as many as 10,000 varieties! Surprised? Please do not be. These are hard facts and data collected from various libraries and sources. Take for example, Sir William Wilson Hunter (1840–1900), a Scottish historian, statistician and an ICS officer who was the first to document 556 rice varieties in Jalpaiguri, Nadia and Malda in his famous book ‘A Statistical Account of Bengal’. Later, many others have contributed to this seemingly incomplete documentation.

Surprisingly, even 10% of this indigenous wealth has not been evaluated, in terms of nutrition, grain-yield and suitability in marginal lands that are drought prone or flood prone. Leading rice scientist, Dr. Radhelal Harelal Richharia of the Central Rice Research Institute, Cuttack, raised questions about the effectiveness of the Japonica varieties in Indian soil and spoke about the spread of pests and diseases in the Indica varieties. His report from the 1960s remains obfuscated.

Recent reports also highlight this same treasure of Bengal. According to a report of the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (2007–08), more than 82,700 varieties of rice were selected and cultivated by farmers in the Indian subcontinent. These varieties were selected and developed from a single crop species of rice called the Oryza sativa by our visionary forefathers, to meet the food security of the huge population of the country. Surprisingly, even 10% of this indigenous wealth has not been evaluated, in terms of nutrition, grain-yield and suitability in marginal lands that are drought prone or flood prone. Leading rice scientist, Dr. Radhelal Harelal Richharia of the Central Rice Research Institute, Cuttack, raised questions about the effectiveness of the Japonica varieties in Indian soil and spoke about the spread of pests and diseases in the Indica varieties. His report from the 1960s remains obfuscated.

Replacing region-specific, salt-tolerant Folk Rice with modern varieties of rice was a costly mistake because it became clear that the modern varieties could not survive in the marginal environmental conditions. The time-tested wisdom of traditional practices of the local population was severely ignored and the folk paddy varieties gradually got lost.

Interestingly, each variety was unique with a specific character: disease resistant, high-flood and drought tolerant, high grain-yielder, aroma etc. Farmer-selected crop varieties are not only adapted to local soil and climatic conditions but are also fine-tuned to diverse local ecological conditions and cultural preferences. For example, the Kalonunia and the Chamarmani varieties are blast-resistant. The low-lying areas are replete with flood-tolerant varieties. A wide genetic base provides a ‘built-in insurance’ against crop pests, pathogens and climatic vagaries.

Also read : When your Food turns Junk

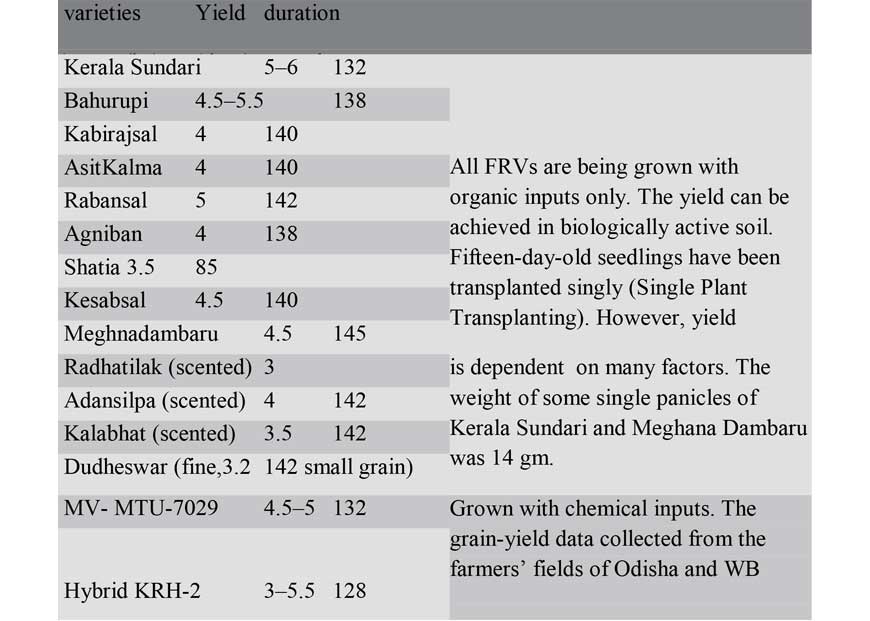

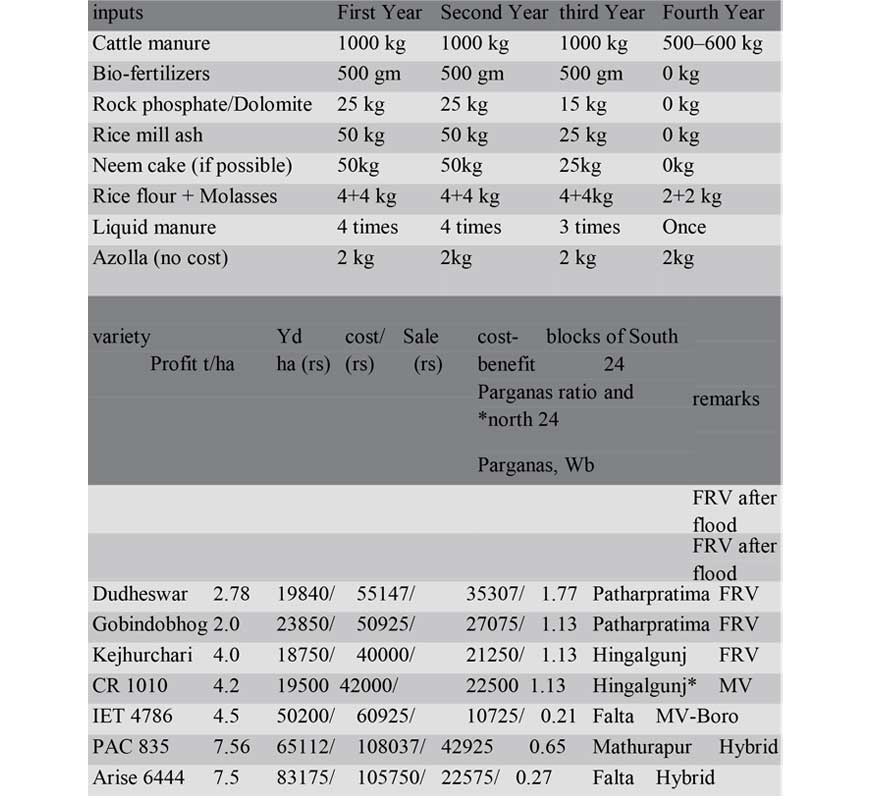

Requirement of organic inputs Per bigha (33 decimals)

I realized the so-called High Yielding Varieties (HYVs) of paddy was just a myth. In order to combat the perceived threat of famine in the mid -sixties, the concept of cross breeding led to a substantial grain-yield creating new paddy varieties in Bengal like TN1, IR 50, 20, etc. During the initial years of Green Revolution, these miracle seeds out-performed the Folk Varieties

I realized the so-called High Yielding Varieties (HYVs) of paddy was just a myth. In order to combat the perceived threat of famine in the mid -sixties, the concept of cross breeding led to a substantial grain-yield creating new paddy varieties in Bengal like TN1, IR 50, 20, etc. During the initial years of Green Revolution, these miracle seeds out-performed the Folk Varieties, where farmers could purchase certified chemical fertilizers, pesticides and do other inter-cultural operations. Nearly 600 HYVs were developed by crossing the indica and the japonica or a selection from the cross. But contrary to popular belief, the HYVs, did not give a high grain-yield everywhere, especially in marginal lands such as flood-drought-and saline-prone areas, rendering the abbreviation HYV inappropriate. They can at best be called the Modern Varieties (MVs). The average grainyield of the most popular HYV-MTU 7029 has plummeted from 5.5 tonnes to 4.5 tonnes per ha despite heavy application of fertilizers, pesticides and certified seeds from the market. The grain-yield of any of the indigenous varieties, meanwhile, has remained the same.