Bengal’s eye of the needle – Kantha fabric art

Except for a few forms, folk art has always concerned itself with a definite purpose of its object, be it a lamp or bell or utensil. Articles having certain utility, gain an aesthetic dimension in the hand of the folk artist who meticulously infuses the skills that was passed down to him or her over generations. They never deviate, and seldom venture to relate their own thoughts through the craft. Bengal’s age old and unique textile form of Kantha stands apart from the rest of the ethnic art forms.

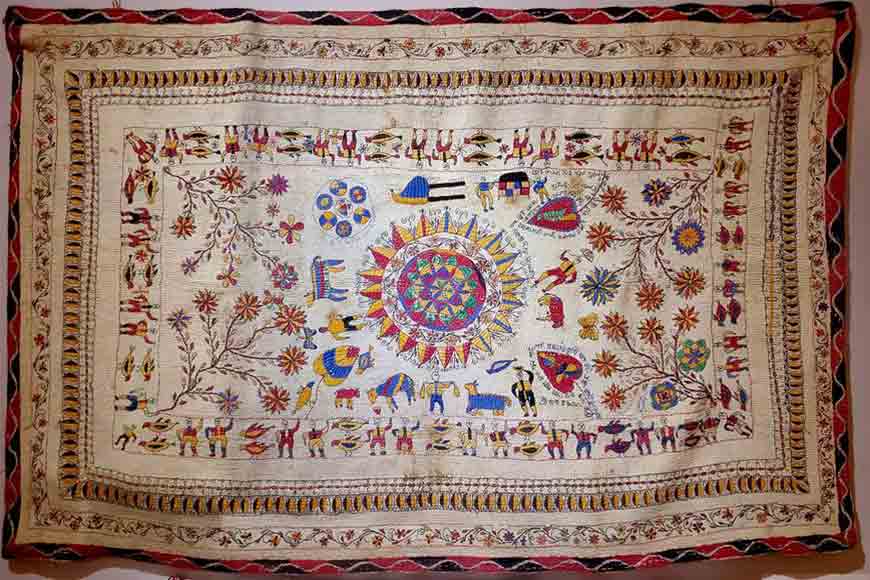

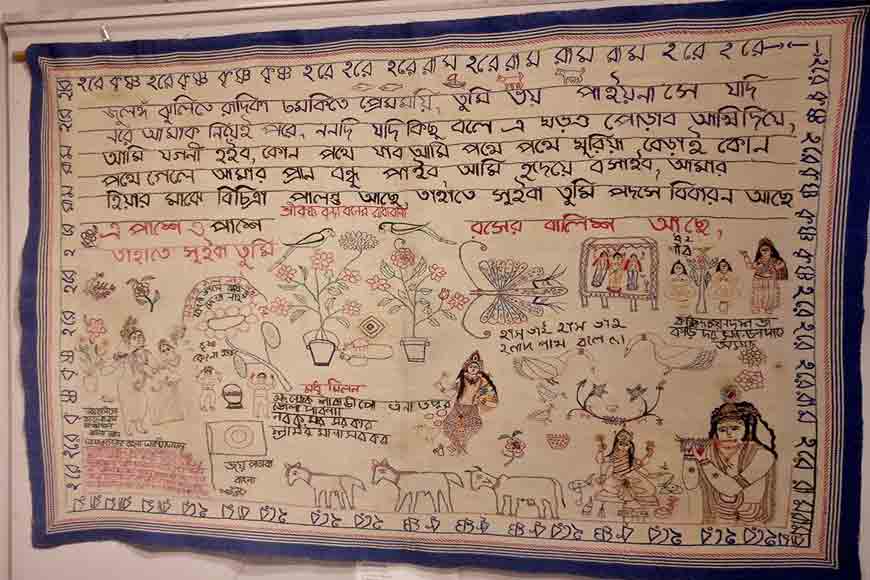

Executed exclusively by women using traditional techniques such as other folk arts; kanthas serve a particular function of blanket or spread, just as much as they give voice to the most intimate tales, beliefs, joys and tears of the individual. Furthermore, unlike the other folk traditions, kantha is an art of what we call ‘recycling’ in today’s common parlance. Old unusable pieces of sarees and other fabrics are painstakingly stitched together to give birth to a fabric even more valuable. The art of kantha is inherently feminine.

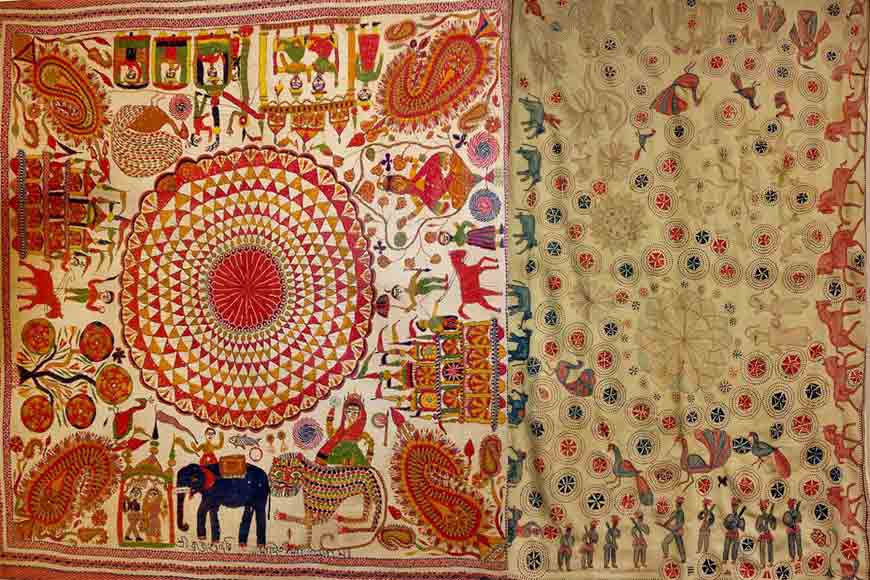

There are different specimens of Kantha, such as Sujni kantha (bed spread), beytan (wrap), durjani (wallet), bostani (wrap) arshilata (mirror cover); along with some common forms like pillow cover, handkerchief, ashon kantha (seat). Century-old pieces from Bangladesh and West Bengal represent extinct styles and stitching techniques. Stitches ranging from embroidery to darning and the use of naturally yet permanently dyed threads is unique to Bengal’s Kantha work.

Thematically, kanthas are as diverse as their technique. On one hand some are mostly abstract patterns emphasizing repetitive and rhythmic decorative elements meant to captivate the eyes of the viewer. Recurring motifs often bear the identity of their origin in a particular region. On the other hand, some kanthas are loaded with narratives rooted in mythology, folklore, folk belief and daily experiences of life. Animals and plants from facts and fantasy, figure seamlessly in the works. Chimeric creatures, mundane familiar objects, humans, deities, fantastic plants, animals, and birds coexist on the ground of the fabric which might be read as an allusion of the fertile soil, moistened by the characteristic tenderness and tolerance of the archetypal womanhood of Bengal. However, the motifs assume a greater psychological, anthropological and naturalistic significance than mere ornamentation when they signal towards a world of symbolic imagery. For instance, a pair of dancing peacocks symbolizes fertility; flowers sometimes suggest knowledge and sometimes the female genitalia.

The aesthetic excellence elevates some of the pieces to such a level that touches the sensibility of western modern art. Though not devoid of figurative elements, the all-white seat kantha, for example, is often reminiscent of Robert Ryman and Agnes Martin’s work - at least visually. And the same goes for the red one as it strikingly resembles the all over canvases of the twentieth century abstract expressionists in terms of both surface texture and expression.