Bengal Famine of 1943, Britain’s worst human rights violation on Indian soil?

More people were killed in the Bengal Famines of 1770 and 1943 than the number of Jews killed by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime. But since there is no special day of remembrance for them, today, Human Rights Day, is as good an occasion as any to remind ourselves of what must never be forgotten - perhaps the worst human rights violations committed on our soil. The Bengal Famine of 1943 in particular was caused not by drought but by a complete and deliberate policy failure of the British government in England led by Winston Churchill, a theory that received scientific backing through a study published in 2019.

The authors of the study, led by an associate professor at IIT Gandhinagar, studied six major famines in the Indian subcontinent between 1873 and 1943, and concluded that the Bengal famine was the only one not linked directly to soil moisture deficit and crop failures. “The Bengal famine was likely caused by other factors related at least in part to the ongoing Asian threat of World War II, including malaria, starvation and malnutrition,” the study said.

It added that the damage caused to Bengal’s economy by the military and political events of 1943 was aggravated by refugees from Myanmar (Burma). Primarily, however, it was the wartime grain import restrictions imposed by the British government that played a significant role in the famine.

Some might say this is old news. After all, Amartya Sen had argued as far back as 1981 that there should have been enough supplies to feed Bengal in 1943. And in ‘Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India’ (2017), Shashi Tharoor wrote, “Churchill deliberately ordered the diversion of food from starving Indian civilians to well-supplied British soldiers and even to top up European stockpiles, meant for yet-to-be-liberated Greeks and Yugoslavs.”

Also read : ‘Germany felt that Russia should invade India’

It is possible to argue that the impact of that human rights catastrophe is still being felt. An estimated 3 million (out of a population of 60 million) people died of starvation, malaria, and other diseases aggravated by malnutrition, population displacement, unsanitary conditions, and lack of healthcare. Millions were impoverished as families disintegrated, men sold their farms and left home to look for work or join the Army, and women and children became migrants, often travelling to Calcutta or other large cities in search of relief. The massive disruption to Bengal’s social fabric, some may argue, has still not been entirely repaired.

What made it worse was that, owing to both natural and artificial causes, agriculture in Bengal had been on the decline for a number of years prior to World War II, a fact certainly not unknown to the British-Indian administration. And yet, the deliberate policies of this same administration, such as the destruction of huge amounts of paddy to deny food supplies to the enemy in case of a Japanese invasion, or the denial of rice imports to Bengal on the pretext of building wartime food stockpiles in Europe, made the situation infinitely worse.

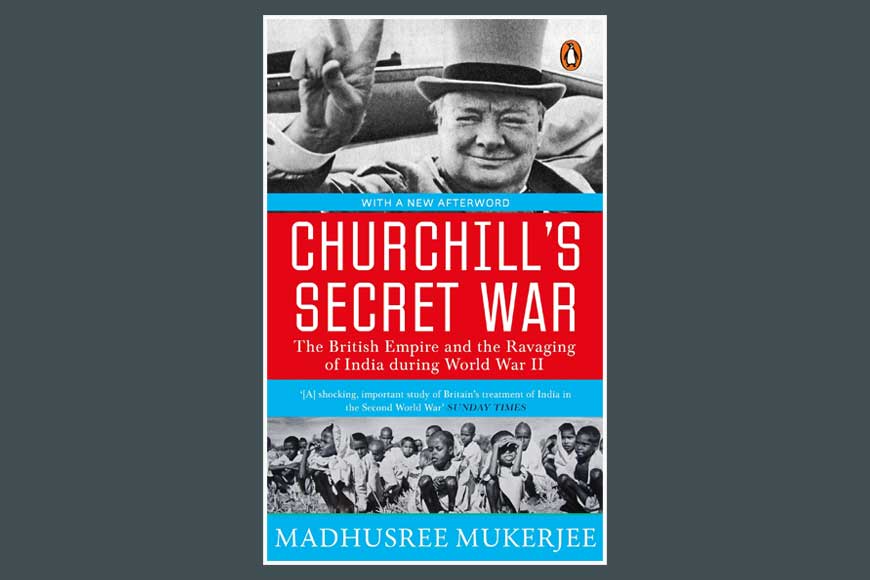

And yet, efforts had been made to avert the disaster. As early as December 1942, high-ranking government officials (including John Herbert, Governor of Bengal, Viceroy Lord Linlithgow, Secretary of State for India Leo Amery, General Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in India, and Admiral Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Commander of South-East Asia) had been requesting food imports for India, but for months, these requests were either rejected or reduced to a fraction of the original amount by Churchill’s War Cabinet. In her book ‘Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War II’ (2010), Madhusree Mukherjee wrote, “The War Cabinet’s shipping assignments made in August 1943, shortly after Amery had pleaded for famine relief, show Australian wheat flour travelling to Ceylon, the Middle East, and Southern Africa - everywhere in the Indian Ocean but to India. Those assignments show a will to punish.”

So on Human Rights Day, let us take a moment to remember the 3 million people of Bengal sacrificed at the altar of government policy, human callousness, racism, and arrogance. And let us end with a remark attributed to Churchill upon hearing of the death toll from the Bengal famine: “I hate Indians. Beastly people with a beastly religion. The famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits.”