Bangladesh at 50, defined by ‘Bengaliness’

In an interview given in 1946, venerable Congress leader Maulana Abul Kalam Azad told journalist Shorish Kashmiri, “The other important point that has escaped Mr Jinnah’s (Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Dec 25, 1876-Sep 11, 1948, the founder of Pakistan) attention is Bengal. He does not know that Bengal disdains outside leadership and rejects it sooner or later... I feel that it will not be possible for East Pakistan to stay with West Pakistan for any considerable period of time. There is nothing common between the two regions except that they call themselves Muslims. But the fact of being Muslim has never created durable political unity anywhere in the world.”

His prophetic words found an echo in Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (popularly known as ‘Frontier Gandhi’) and the Congress’ one-time education minister Humayun Kabir. Earlier, in 1905, even Lord Curzon had failed to divide Bengal despite a failed attempt at partition. It was then that Rabindranath Tagore wrote ‘Amar Sonar Bangla ami tomay bhalobasi’ (My golden Bengal, you are my beloved), which became the national anthem of Bangladesh post-Liberation.

Jinnah paid absolutely no attention to the words of Maulana Azad. West Pakistan oppressed East Pakistan, depriving it in every possible way. It was West Pakistan which decided the price of jute made in East Pakistan, in fact the price of all agricultural produce. East Pakistan would get only half of the revenue thus earned. Items such as apples, grapes, and woollens from West Pakistan would cost almost 10 times as much in the East. Even the newspapers and magazines published in East Pakistan had to hand over part of their revenues to the West. Such was the disparity and discrimination that anyone who protested would be labelled as a traitor to the nation, anti-Pakistan, anti-Islam. Torture, arrest, imprisonment were routine.

Following the template of the All India Congress, the All India Muslim League had come up in Dhaka’s ‘Ahsan Manzil’ in 1906. Significantly, the league initially included no leaders from the rest of India, except those from the east. In later years, of course, Muslim intellectuals from north India did join in, chief among them being scholars from Aligarh Muslim University, including vice-chancellor Dr Ziauddin Ahmed in 1930.

Following the template of the All India Congress, the All India Muslim League had come up in Dhaka’s ‘Ahsan Manzil’ in 1906. Significantly, the league initially included no leaders from the rest of India, except those from the east. In later years, of course, Muslim intellectuals from north India did join in, chief among them being scholars from Aligarh Muslim University, including vice-chancellor Dr Ziauddin Ahmed in 1930. Jinnah remained an active member of the Congress for two decades, speaking about Hindu-Muslim unity.

The prime minister of Bengal province at the time, A.K. or Abul Kasem Fazlul Haque, was known in Bengali circles as ‘Sher-e-Bangla’. Between March 22 and 24, 1940 in Lahore, at the ‘Pakistan Resolution’ session, Mohd Zafarullah Khan presented the ‘Declaration of Independence of Pakistan’ which he himself had crafted. The responsibility of getting the proposal passed next year went to Sher-e-Bangla.

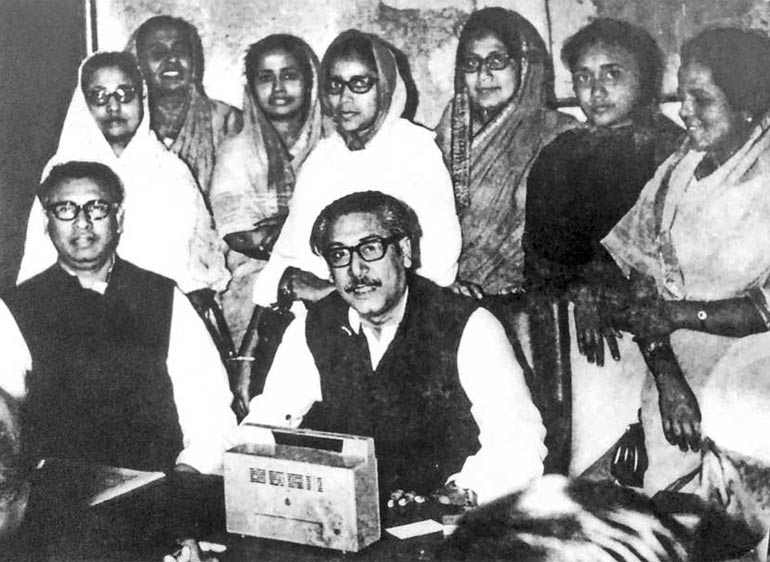

More than two decades later, once again in Lahore in 1966, at a national conference of Opposition leaders, the Awami League delegation led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman presented ‘six demands’ to end the perceived exploitation of East Pakistan by West Pakistan. They had been left with little choice but to do so. The ‘six-points’ contained the seeds of an independent Bangladesh, and the military intelligence branch of West Pakistan saw this before anyone else. Experienced politician that he was, Sheikh Mujib had invested every line of the six-point charter with the kind of reasoning that, although it could not be called separatist out of respect for the sovereignty of Pakistan, was a clear indication of its breaking up. And so was born the Agartala Conspiracy Case, brought by the government of Pakistan in 1968 against Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and 34 others. The Awami League became a hunted entity, and Mujib was relentlessly hounded for allegedly conspiring with India against the stability of Pakistan.

Importantly, post-Liberation, the widely respected Communist leader Comrade Mani Singh had said, “Bongobondhu (Mujib) had decided in favour of independence in 1951 itself.” This statement, based on Singh’s ‘Sangramer Notebook’ published on the occasion of Mujib’s 53rd birthday, was published in ‘Dainik Sangbad’.

In support of the six-point charter, Bongobondhu and his Awami League went on a spree of public lectures and speeches from March 1966. After public gatherings at Dhaka, Chittagong, Jessore, Khulna, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Pabna, and Faridpur, he was arrested and imprisoned. Though he was soon free again owing to legal loopholes, he did not remain free for long. Pakistan’s military dictator Ayub Khan refused to accept the six-point movement, and came up with the Agartala Conspiracy angle, which meant that Mujib was repeatedly arrested from May 8, 1966 onwards, which threw Bangladesh into turmoil.

From the third week of May itself, the whole of East Pakistan was determined to secure Mujib’s release from prison. The ferocity of the demand blindsided Pak leaders, the consequence of which came in the form of section 144, curfews, bullets, and killings. Defiant, the people filled the streets nonetheless. And then came 1969, and the famed ‘Unoshottorer Andolan’ (1969 Movement). Among the many slogans of the time were, ‘Joy Bangla’; ‘Tomar amar thikana, Padma Meghna Jamuna’ (your address and mine, Padma Meghna Jamuna); ‘Jail er tala bhangbo, Sheikh Mujib ke anbo’ (break the prison, free Mujib); ‘Dhaka or Pindi (Rawalpindi, then the capital), Dhaka Dhaka!’; ‘Punjab or Bengal, Bengal Bengal!’; ‘Amar desh tomar desh Bangladesh Bangladesh’; and many more. I wrote three of the slogans myself! Significantly, the placards, festoons or slogans made no mention of East Pakistan or even East Bengal. It was Bangladesh all the way.

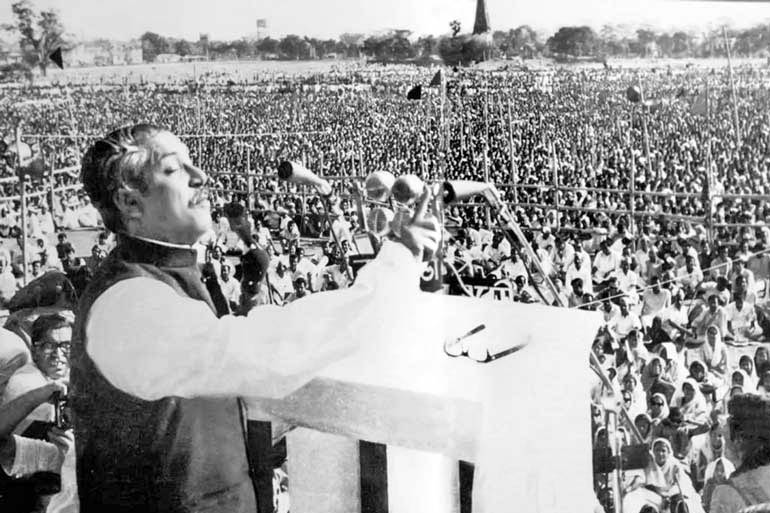

Bongobondhu spoke for 19 minutes. “This time, the fight is for freedom.” That was it, no other declaration was needed. This was the day when the declaration of independence was made, and the days ahead would be filled with a bloody battle for Liberation that left 30 lakh martyrs, and attained freedom.

Events unfolded rapidly after this. Most of which has been well documented in the pages of history. However, one incident remains as fresh in my mind as when it happened. On March 3, 1971, Dhaka was under curfew. As we worked to set up a barricade at the Malibagh traffic island, a military truck rushed up to us, firing indiscriminately. In front of my eyes, Farooq Iqbal slumped to the ground. Only a minute ago, I had left his side to stock up on bricks and stones. Farooq Iqbal became the first martyr of Bangladesh’s fight for independence.

On March 7, Bongobondhu was scheduled to speak at the Race Course grounds at 2.00 pm. The distance from our Malibagh home was not even two miles, and we were there at 10.00 in the morning, in case we couldn’t get seats later! The ground was packed to overflowing, many people had climbed trees or to the rooftops around the grounds for a view. Bongobondhu spoke for 19 minutes. “This time, the fight is for freedom.” That was it, no other declaration was needed. This was the day when the declaration of independence was made, and the days ahead would be filled with a bloody battle for Liberation that left 30 lakh martyrs, and attained freedom.

The Pakistani genocide began post-midnight on March 25, which is why March 26 became Independence Day. Two days later, the first refugees streamed into India, a traffic that continued until the end of November. India provided the only support for Bangladesh’s War of Liberation. Indira Gandhi remains integral to the battle for freedom, her contributions never to be forgotten. And a lasting salute to the Indian Army, too. Today, Bangladesh celebrates its 50th year of liberation, while united Pakistan did not even last 25. What happened to religion, to the two-nation theory?

In an interview given in 1946, venerable Congress leader Maulana Abul Kalam Azad told journalist Shorish Kashmiri, “The other important point that has escaped Mr Jinnah’s (Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Dec 25, 1876-Sep 11, 1948, the founder of Pakistan) attention is Bengal. He does not know that Bengal disdains outside leadership and rejects it sooner or later... I feel that it will not be possible for East Pakistan to stay with West Pakistan for any considerable period of time.

There would have been no Pakistan without dividing India. There would have been no East Pakistan without Pakistan. There would have been no Bangladesh without East Pakistan. It was none other than Jinnah who fuelled the birth of Bangladesh. Barely eight months had passed since the creation of Pakistan when, in March 1948, he arrived in Dhaka to address a public gathering at Race Course Maidan and the day after, on the premises of Curzon Hall, the students’ residence at Dhaka University. At both venues, he declared that the national language for both Pakistans would be Urdu. He seemed to entirely forget that the people of East Pakistan neither knew nor spoke Urdu, that their only language was Bengali. His declaration prompted the Language Movement or ‘Bhasha Andolan’, as well as the War of Liberation, eventually. On December 16, 1971, Bangladesh became free. From that day, that month, that year, West Pakistan would be simply Pakistan. In that sense, this day marked the birth of Pakistan too, which makes this year their 50th anniversary as well.

A Pakistani novelist from Karachi who I met in London jokingly told me, ‘Mohammed Ali Jinnah is the reason both Pakistan and Bangladesh were born.’ A common religion does not necessarily indicate commonality in the matters of nation and community. A scholar and veteran politician, Jinnah died before he could witness the outcome of his wilful blindness. My response to the novelist, ‘The world knows us as Bangladesh, the reason being Bengalis.’

Also read : A museum that keeps the truth of 1971 alive

Bangladesh drafted its Constitution in 1972. Its four pillars were - democracy, socialism, religious impartiality (secularism), and Bengali nationalism. All four vanished once Bongobondhu was murdered. Though the apparel of democracy is still outwardly visible, given that elections are held.

In place of Bengali nationalism, the BNP’s military President Ziaur Rahman created ‘Bangladeshi’ nationalism. The ‘Muslim’ component inherent in ‘Bangladeshi’ made Bengali irrelevant. The autocratic Ziaur Rahman also reinstated the hitherto banned Jamaat Islam, awarding Bangladeshi citizenship to Pakistani citizen ‘Amir’ Ghulam Azam of the Jamaat, the logic behind this being that he was originally from Bangladesh, though he had sought refuge in Pakistan when the two nations were divided.

Yet another autocrat, Hussain Muhammad Ershad, went a step further, adding the word ‘Bismillah’ to the already battered Constitution. Islam became the state religion. No political party came out strongly in protest, no processions were taken out. Did Hindus, Buddhists and Christians disappear from Bangladesh? Were they no longer Bangladeshi citizens? Or were they second class?

That tradition has continued. Bongobondhu’s daughter Sheikh Hasina has now been the Prime Minister for over a decade. And she has retained both ‘Bismillah’ in the Constitution, as well as Islam as the state religion. During her first bid for power, she had promised to bring back the four pillars of the Constitution, a promise she failed to keep not just the first time, but the second time round as well. Instead, she seems to be clinging to Islam with increasing desperation, practically a hostage to the Islamic countries and parties. Every neighbourhood now boasts numerous mosques, the country is overflowing with madrasas which thrive on government support. You would have to search with a microscope to find a school or college teaching science. The mullahs and malulavis with their fatwas grow ever stronger. The government, dependent on petro dollars from Islamic countries, turns a blind eye.

The past 50 years have revealed many facets of Bangladesh: the assassination of Mujib, two stints of military rule, the formation of SAARC at Ziaur Rahman’s behest, a military coup, the murder of Ziaur Rahman, three caretaker governments, two successive women prime ministers, more than 100 political parties (most of them Islamic), including Ershad’s Jatiya Party, Bangladeshi migrant workers in Malaysaia and the Middle East, over 1 million Bangladeshis travelling abroad as workers, students, labourers.

Muhammad Younus’ Grameen Bank has fetched him a Nobel Peace Prize. Fazle Hasan Abed’s BRAC is the world’s largest NGO, spread across more than 50 countries. Over 92 percent Bangladeshi schools have girl students, and women comprise more than 80 percent of the workforce in its textile sector. Bangladesh earns most of its foreign exchange from workers abroad and its garments industry, which is rising steadily. The two women leaders - Sheikh Hasina of Awami League and Begum Zia of the BNP - are locked in a circle which includes several Islamic parties. Neither leader has been able to turn down the strident demands made by these parties, and the more they grow, the lower the progressives sink. The once revered and idolised Communist Party is now almost non-existent, making only occasional appearances in the media.

American President Richard Nixon’s foreign secretary Henry Kissinger had called Bangladesh a ‘basket case’ in 1971. I ran into Kissinger about 15 years ago, at a programme on refugees and global culture organised by Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt (World Cultural Center). He was shaking hands pretty freely, so I stuck my hand out, too. Before he shook it, he asked me, ‘From which country are you?’, probably thinking I was Indian or Pakistani. When I said Bangladesh, he withdrew his hand. Even so, I asked him, ‘So, you are the man who said Bangladesh was a basket case?’ He did not answer. He had none.

Nixon and Kissinger had been unable to digest the defeat of their beloved Pakistan. During the War of Liberation, they had sent warships to lend strength to the fight against Bangladesh, and had been vocal about Indian ‘imperialism’. They were even hesitant about acknowledging an independent Bangladesh.

Let America see both Pakistan and Bangladesh today. As per a March 2021 report, the World Bank says, ‘Bangladesh has left behind Pakistan in every aspect.’ The per capita income is 2,064 USD, GDP is 52, bank reserves total USD 42 billion. Pakistan has hardly 20 billion, and ranks lower on the school education index. The pride in our 50th year of Independence trumps religion and the two-nation theory.

Bangladesh is free, and in its 50th year, a proud global entity. Everywhere, Bangladesh and Bengalis can hold their heads high.

Translation: Yajnaseni Chakraborty