At home in the world, revisiting the memoirs of Amartya Sen

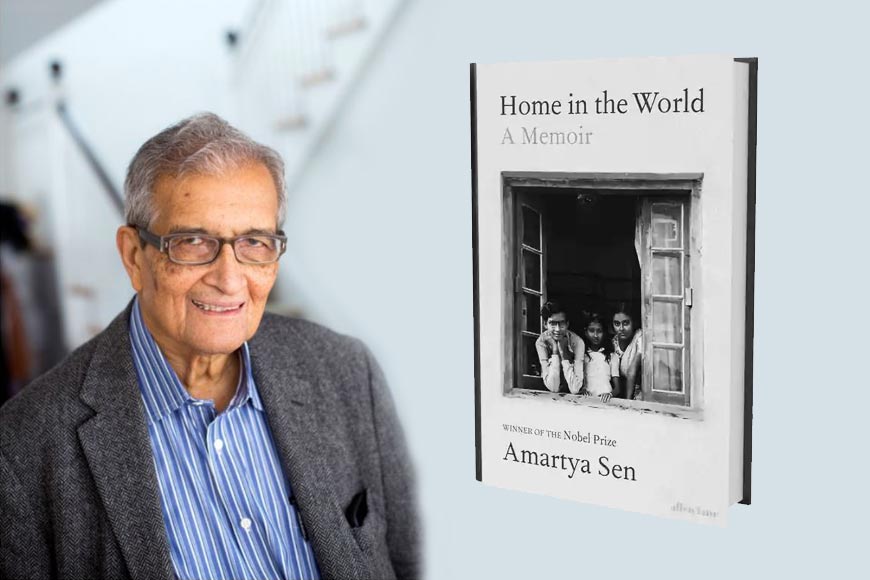

Home in the World: A Memoir

Amartya Sen

Allen Lane, Rs 899

As a young Amartya Sen sets foot in Cambridge for the first time, he writes, his excitement of visiting a new place is combined with the grief of severing his umbilical cord from his motherland. The quintessential traveller, who has been on an adventure all his life, on a journey that can only be called majestic, inspiring millions to dream. His lucid writing lends wings to his concept of 'home', and the vast world outside.

Sen’s vast knowledge and wisdom are peerless. There are very few people in the world who have not heard of Amartya Sen, inventor of the human development index (HDI, a summary composite measure of a country's average achievements in three basic aspects of human development: health, knowledge and standard of living). He was the first non-American academic to be awarded the National Humanities Medal despite not being a US citizen. His work on social choice theory is seminal, and his writings on poverty, famine, and development, as well his contributions to moral and political philosophy, are important and influential.

Sen's views on the nature and primacy of liberty also make him a major contemporary liberal thinker. The world reveres the role of the Nobel Laureate in welfare economics, social election theory, economic development and social justice, economic theory of famine and welfare of the people of developing countries.

Yet while reading Sen's memoirs, I have been surprised by his strong attachment to his roots. He considers and defines himself as a pupil who is still learning, writing of how, having been born in a university campus, his tryst with campus life has continued as he moves from one campus to another. The allusion is very clear -- the university campus is his home and his world.

He has spent more time on campuses than at home – the archetype of an ideal and successful student. Although he has been associated with different campuses in different countries all his life, however, he has always felt the pull of his homeland, as he mentions repeatedly in his book. These emotions, not easy to express, he has kept to himself for years.

Born on November 3, 1933, he was christened by none other than yet another of Bengal's Nobel Laureates, Rabindranath Tagore. Amartya’s maternal grandfather was Acharya Kshitimohan Sen, professor of Sanskrit literature, a close associate of Rabindranath Tagore at Santiniketan and the second Vice-Chancellor of Visva-Bharati. Amartya's father Ashutosh Sen was a professor in the Department of Chemistry at Dhaka University.

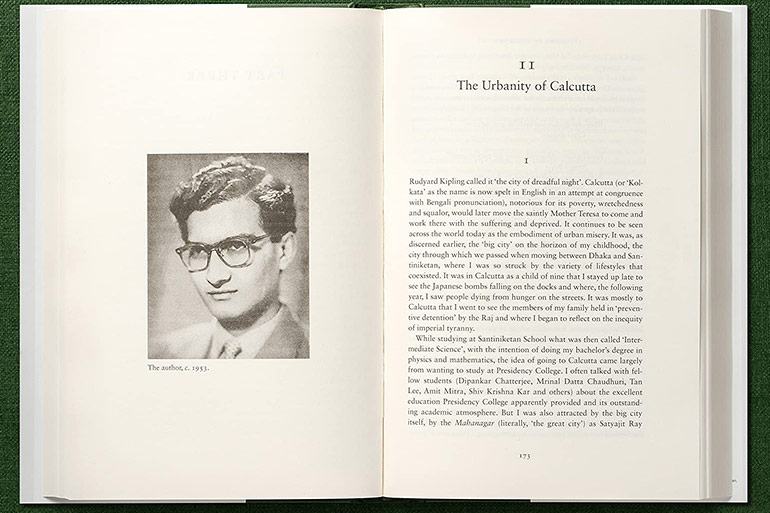

The book is a journey of Sen’s life starting from his early years in Dhaka. He began his school education at St Gregory's School in Dhaka in 1940. In the fall of 1941, Sen was admitted to Patha Bhavana, Santiniketan, where he completed his school education. In 1951, he went to Presidency College, Calcutta, and was a varsity topper with an honours degree in Economics. While at Presidency, Sen was diagnosed with oral cancer, and given a 15 percent chance of living beyond five years. With radiation treatment, however, he survived and in 1953 moved to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he earned a second B.A. in Pure Economics in 1955 with a First Class, topping that exam as well.

While Sen was officially a PhD student at Cambridge (though he had finished his research in 1955–56), he was offered the position of First-Professor and First-Head of the Economics Department of the newly-created Jadavpur University. Needless to say, at 23, Sen was the youngest professor and department head of a university in the academic history of India. He served in that position, starting the new Economics Department, from 1956 to 1958.

A reader must have noticed that Sen mentions Visva-Bharati campus as the place he was born, underlining the fact that a campus is the ideal birthplace for a learner. Sen admits that an academic institution’s campus instils broad and liberal perceptions of humanism, creates a logical and scientific bend of mind, provides an exposure to cultural ethos and helps in the overall development of a human being. Sen writes that it was in Santiniketan that his views on education first took shape. There boys and girls studied together and the academic realm was liberal and progressive. The four fundamental principles of Tagore's educational philosophy - naturalism, humanism, internationalism and idealism - impacted Sen deeply.

It is surprising to note that Sen has worked for about 13 educational institutions in the world. Since his childhood, his association with esteemed academic institutions has remained a leitmotif in his life. He has spent his entire academic career and his life in the campuses of distinguished seats of learning including Harvard, Cambridge, Oxford, London School of Economics, Jadavpur University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Stanford, California, Berkeley, Calcutta University and Nalanda University.

He has pursued knowledge with a single-minded determination and all the prestigious awards he has received during his long and eventful career, including the Nobel Prize and Bharat Ratna, are an acknowledgment of his academic brilliance. Time and again he has mentioned that in Santiniketan, he learnt to live harmoniously, where education was intended to arouse the curiosity of the students instead of creating a competitive spirit. Gurudev had set up the institution at Santiniketan with a specific objective in mind - to cultivate a love for nature, to impart knowledge and wisdom in one's native language, provide freedom of mind, heart and will, a natural ambience, and to eventually enrich Indian culture - and this was the guiding approach to education too.

Sen has also explored the historical and cultural aspects of Bengal in his memoirs. He has squarely blamed political persuasion behind the Hindu-Muslim animosity. A witness to the Great Bengal Famine of 1943, he also writes about members of his family who were imprisoned by the government for opposing and criticising British policies during that period.

Perhaps the most important task of a bona fide academic institution is to provide a liberal education system. While reading this book, it emerges that the author has been searching all his life for people and roots of the soil and his quest has taken him on a whirlwind tour across continents. He has traversed the entire world trying to find an answer, and in the process the world has welcomed him and he has become a global citizen.

I shall conclude this piece by raising a topic here. A group of young journalists from Bangladesh once visited Santiniketan for two days and met Amartya Sen at his home, Pratichi. The Nobel Laureate told them, “Santiniketan is not a place that can be covered in two days. Santiniketan is an emotion, a feeling that cannot be expressed in words.” Perhaps the roots that tug at one’s heartstrings remain ensconced deep within. Amartya Sen has ruled the world, but his roots remain entrenched deep within his heart. Let this ideal flourish in the rose gardens of ages to come. Let them turn crimson and sprinkle love.