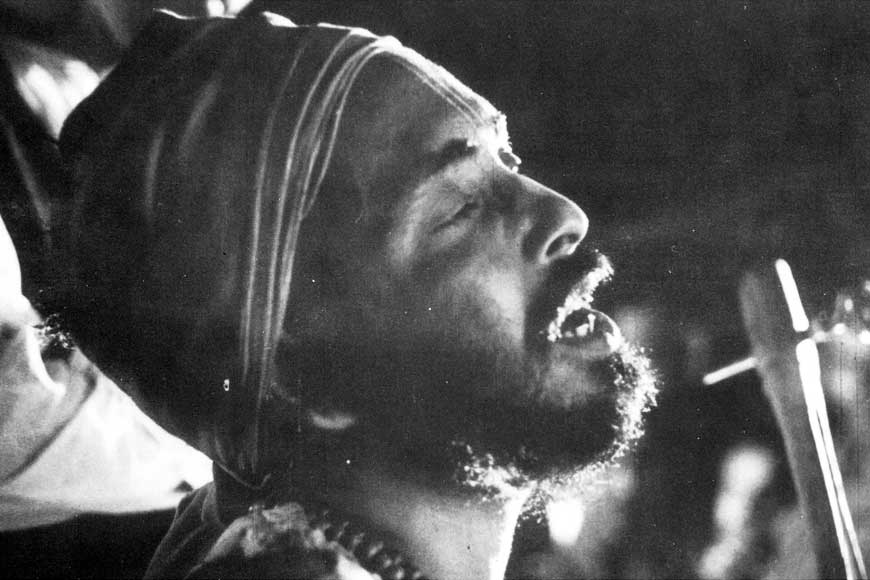

An artist, a thinker, a loner - remembering Ritwik Ghatak on his birthday

Born in Dhaka on November 4, 1925, Ritwik Ghatak began his career as a litterateur quite early. After Partition in 1947, he felt restless and rootless at the same time. Disturbed by his rootlessness, he wrote, “My feet are not on my soil, that’s my obstacle. How shall I find another soil, and when? Because I have to return to my mother’s womb to seek the source of this archetypal idiom.” He joined the IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association) in 1948 in Calcutta and wrote and produced a number of plays of which Dalil remains a masterpiece. He translated Bertolt Brecht’s A Caucasian Chalk Circle in Bengali. When his film Nagarik faced distribution troubles, Ritwik went to Bombay and joined Filmistan as a scriptwriter, but neither the job nor the city suited him and he returned to Calcutta.

An extraordinary artist, a Marxist, and a loner, Ritwik Ghatak was only 51 when he died in Calcutta on February 6, 1976. Had his first feature film Nagarik (1952-53) been released immediately after it was made, the history of Indian cinema may have been written differently. Pather Panchali came in 1955 and made history, but Ritwik could not release Nagarik during his entire lifetime. It was only made available to Indian audiences 30 years after it was made, in 1982.

A student of Krishnanath College in Berhampore, he was 22 when he vented his pent up anger and frustration in his first unpublished story Dalil (The Document), using the typical Dhaka dialect in writing it. When it was adapted and staged as a play by IPTA, Ritwik played an important role in it. As he wrote, “You can sever Bengal, but not its heart.” He wrote, produced and acted in nine plays. One was Tagore’s Bisarjan (The Immersion), followed by his own translations of Brecht’s Galileo and Caucasian Chalk Circle. He dropped out of postgraduate studies to assist Manoj Bhattacharya in Tathapi. By then, he was convinced that cinema was the only medium which had the power to inspire the masses.

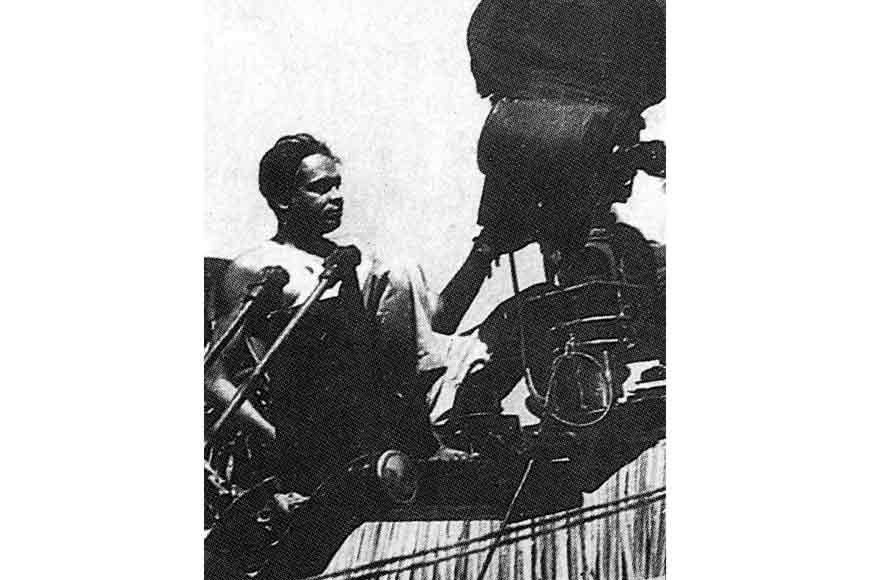

In 1951, he made the transition from theatre to cinema. In 1969, he wrote, “I came to cinema for this, not for filmmaking for its own sake. If a better medium comes up tomorrow, I shall kick out cinema.” He made five short films between 1970 and 1975 - Chhau Dance of Purulia, Amar Lenin (both in 1970), Yeh Kaun, Durbargati Padma (both in 1971) and the unfinished Ramkinkar (1975).

“Joining films has nothing to do with making money,” he explained. “Rather, it is out of a volition to express my pain and agony for my suffering people. I do not believe in ‘entertainment’ or ‘slogan-mongering.’ I believe in thinking deeply of the universe, the world at large, of the international situation, my country and finally, my own people. I make films for them. In the case of cinema, when the audience starts watching a film, it (the film) also creates - a filmmaker throws up certain ideas, it is the audience which fulfils it. Only then it becomes a complete whole. Film-watching is a kind of ritual. When the lights go out, the screen takes over and then the audience increasingly becomes one. It is a community feeling. One can compare it with going to a church, or a mosque, or a temple.”

He also scripted 17 feature films for nine directors, of which nine were released and eight abandoned. He also played minor roles in six feature films including three of his own - Subarnarekha, Titas Ekti Nadir Naam and Jukti Takko Aar Goppo. His first film was Bedeni, which he took over from another director, but had to abandon it due to a camera flaw.

Also read : Ghatak's war between 'Man and Machine'

The number of projects Ritwik had to give up is hardly small, considering the number of finished and viewed films. Few are aware of his documentary on Indira Gandhi made in 1972, which he had to give up midway. Few know of his having done an ad film for Imperial Tobacco to raise money for Subarnarekha, one of his best and most disturbing films. Other memorable films he had to abandon are Kato Ajanarey (1959) and Bogolar Bongodarshan, stopped after just a week’s shooting in 1964-65.

The most creative period in Ritwik’s career was between 1952 and 1967. It began with Nagarik, followed by Ajantrik, Bari Thekey Paliye, Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komol Gandhar and Subarnarekha, punctuated by a spate of documentaries. Memorable among the latter are Orson (1955), Ustad Allauddin Khan (1963), Fear (1964-65) and Scientists of Tomorrow (1967.) He made Fear during his term as vice-principal of the FTII in Pune. Among his most successful students are Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani. Says Shahani, “The impetus, not only to the obvious narrative content of his films, but to their very language, was given by the tremendous splintering of the social system, of its values, while a facade of a hoary culture was still being maintained. The contradictions of a society that could have modernised itself after attaining formal independence are the prime causes of a deeper division.” Vidyarthy Chatterjee, film critic, writes, “Ghatak lived and died as the Ultimate Marginal Man. When he died, there died with him an epic vision, albeit occasionally flawed, equally if not more important, a constant grappling with varied challenges to create pioneering and lasting works.”

Ritwik’s faith in tradition found expression through the chanting of the Vedas and the Upanishads in his films. He chose a child, or a lunatic, or a drunkard to chant them because, “You can say volumes through that which people apparently neglect, but cannot escape.” Perhaps he was summing up his own life. There was a child in him, vulnerable, helpless. There was a little of the madman in him, seeking stability and peace in the asylum. And he was the sad, ruined, defeated drunkard who could not escape his destiny.

In his essay, Making Cinema (1969), Ritwik explains what he meant by the phrase archetypal idiom. He said, “it is a language which will not say much, in itself suggestive and not burdened by allusion, but nevertheless a full edge, which is not loaded with reference but which reminds. Because the feelings it touches off and its imagery are archetypal. A language which will capture the entire mood in a patriarchal style, apparently dry, but juicy within like a Malda mango.” He discovered this idiom in the prose of Vidyasagar, Abraham Lincoln and in the Bible, in the poetry of the Upanishads and in the films of Flaherty and in Song of Ceylon by Basil Wright.

“Such an idiom has existed in cinema, but I am at a loss not to find it. I am sure cinema should speak this idiom which European cinema will not in this age. Indians can find, if they search. This idiom is born in the white-heat of inspiration - elusive to professional filmmakers who turn out film after film. It is forged in the smithy of the souls of non-professionals who do not speak out except under dire necessity and under pressure of life-and-death problems. This archetypal idiom cannot come unless one is very angry, very much in love, very much in sorrow, and has to be in one’s unconscious.” He was determined to seek this mirage of an idiom. This, interestingly, he wrote from the mental asylum where he was a patient of schizophrenia evolved from a growing split in his sensibility and in his stress.

Some say he died because he persistently failed to cope with the trauma of Partition. He died of the frustration of having failed to reach his kind of cinema to the people. He died of alcohol, of schizophrenia, and of the excessive passion he had for life, for the things he believed in and lived for. His childhood in East Bengal was interlaced with turbulent rivers and blessed with Nature’s abundance. These memories haunted him throughout his life, underscored with the poignant pain of Partition, which fell with the killing impact of the guillotine on his mind and body.