Americans and racial divide on the streets of 1942 Calcutta

It was 1942, the year that defined the fate of an impoverished Calcutta, with the notorious Bengal Famine of 1943 looming large amidst the ravages of World War II. It was during this time that American soldiers landed in Calcutta. But the Great American Dream didn’t, nor did any help for Bengal from America, a nation that modern day Bengalis are keen to settle in.

In his article titled ‘The Bengal Famine of 1943 and the American Insensitiveness to Food Aid’, historian Manish Sinha writes: “In August 1943, Calcutta Mayor Syed Baddruja cabled President Franklin Roosevelt, urging him and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to arrange immediately for the shipment of food grains to India. While Roosevelt passed along the cable to the State Department, which was well aware of the difficult food situation in Bengal, Roosevelt refused to take any action, not intending to provoke British resentment against American interference.”

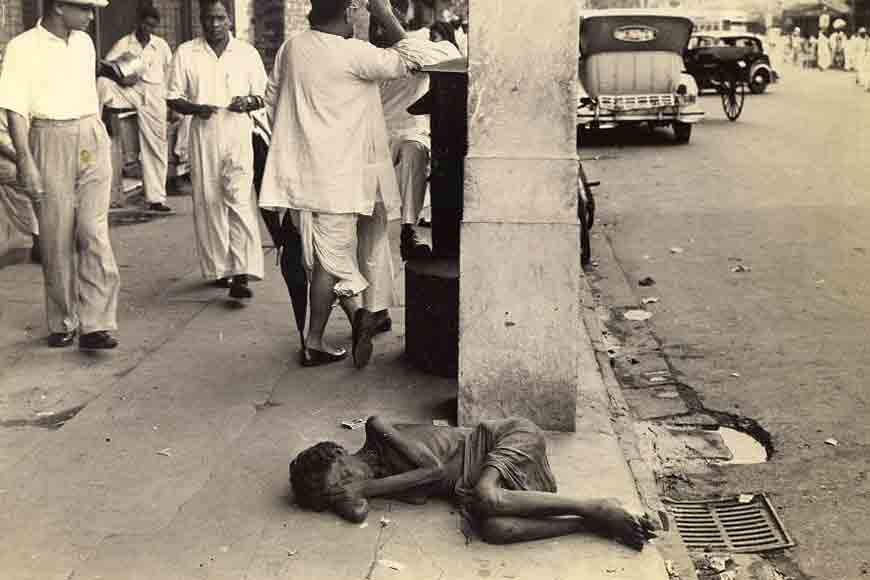

But that did not stop them from sending American troops to a country they were not ready to support. Beginning in 1942, some 150,000 American troops were stationed in Bengal. To help them settle in, pocket-books were given to the soldiers, with detailed instructions on how they must conduct themselves in India. One such book was ‘The Calcutta Key’, with details about Calcutta streets, markets, how to bargain, where to find alcohol, women etc. It asked soldiers to ‘avoid political discussions’, and mentioned the famine conditions. “American troops can expect to see during their time in Bengal hunger and famine…” An American GI mentions how the poor were huddled on the streets, peering through glass windows at the food shops with nothing to eat. But the American government ensured that the GIs did not get too close to the locals.

The British were sceptical about the American troops, who they thought might help the freedom fighters of India. Indeed, Indian politicians did reach out to the American GIs for support. Jayaprakash Narayanan addressed them saying: “You are soldiers of freedom… It is, therefore, essential that you understand and appreciate our fight for freedom. Let your countrymen, your leaders and your government know the truth about India.”

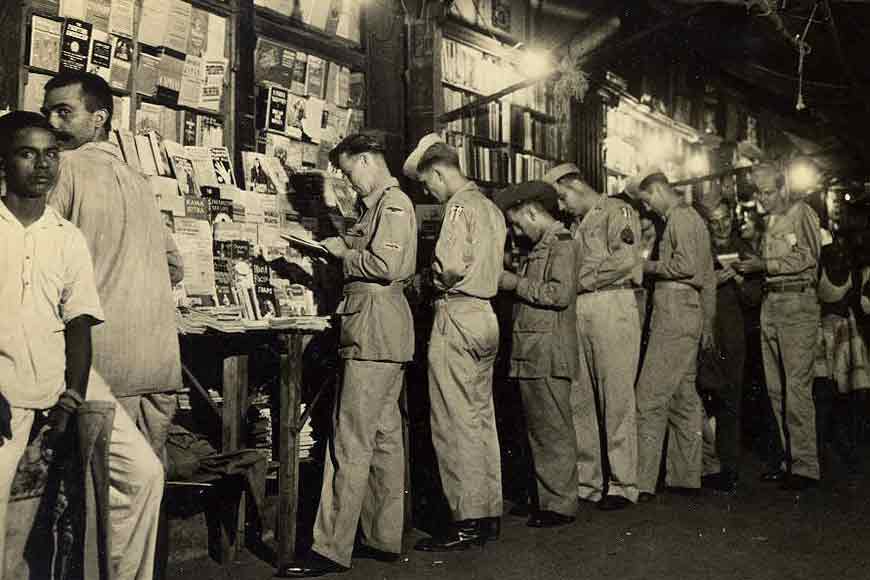

The Americans were more successful in bringing about cultural changes in Calcutta. Legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray, who had returned from Santiniketan to Calcutta after the Japanese air raids, wrote in his autobiography: “Chowringhee was choc-a-bloc with GIs. The pavement book stalls displayed wafer thin editions of ‘Life’ and ‘Time’, and the jam-packed cinemas showed the very latest films from Hollywood.” In his book ‘Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye’, Ray’s biographer Andrew Robinson wrote how, because of the war, Ray was able to see films that had not been released even in London. GIs used to seek out Satyajit at his home and tell him about a US movie playing in town or at their base. Along with movies came jazz - the music that would rock British restaurants in Calcutta - and colas, which had been unknown in Calcutta until then.

But no amount of cultural fervour could mask the misery of Calcutta. In 1944, Geraldine Book, a nurse on overseas duty who landed in Calcutta from Washington DC, wrote: “You could smell Calcutta a hundred miles away. It was a huge city. People were dying in the streets and on the doorways. Everything smells like it’s decaying.” After the fall of Singapore to Japan in February 1942, Calcutta emerged as a vulnerable target for Japanese aggression and turned into a city harbouring thousands of American, African and Chinese troops in its rest houses, hotels and training camps.

It was also thanks to the Americans that Calcutta got a taste of racial divide. Out of the 150,000 American servicemen, 22,000 were Black GIs. Historian Yasmin Khan writes: “While stationed in India, black and white GIs faced blatant and enforced separation. (Black GIs) had fewer canteens, deplorable living conditions, poorer means of entertainment, and were expected to take on more menial labour. In Calcutta, there were segregated Red Cross canteens with Black Red Cross women shipped in especially to staff them. The one service swimming pool in Calcutta had White days and Black days. Black troops were given second class medical treatment, were more likely to catch malaria, had less chance of leave, received harsher treatment from officers and drew the ire of Military Police. As a consequence, Black soldiers made new friends, received invitations to local parties and dances, and were more likely to have an Indian or Anglo-Indian lover.”

Sources: The Raj At War by Dr Yasmin Khan; Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye by Andrew Robinson