After Tagore, author Mahasweta Devi was nominated for 2012 Nobel Prize in Literature

When I first read about Sujata, the mother of corpse number 1084, I could not hold back my tears. I was a college student then and had always been very curious about the Naxal Movement that had rocked Kolkata years before I was born. Heard many tales from my parents about how meritorious students of leading city colleges were killed. But could never fathom the intensity and depth of the pain that these killings had on the families of the sons lost. Mahasweta Devi’s Hazar Churasir Ma was indeed an eye opener for me.

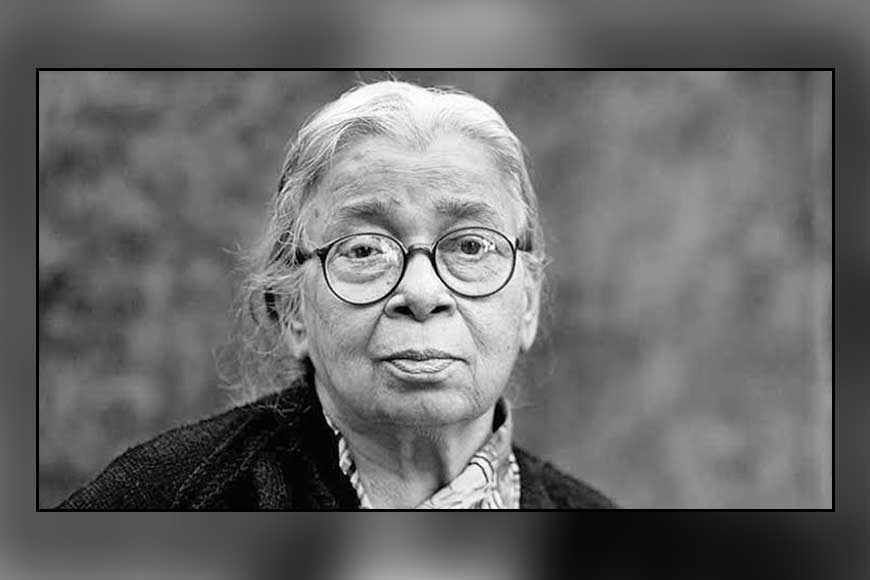

Despite receiving the Nobel Prize of Asia, The Magsaysay Award and also the Gyanpeeth award, Mahasweta Devi could not bag the Nobel Prize. At times I have wondered why? She has been nominated more than once? And her books have always brought out causes of social justice and through her protest pen, she let the pain of human minds flow mellifluously. Take for example, Hazar Churasir Maa. It was almost like a tale of visual brutality. Sujata transformed into a morally assertive, politically enlightened and a socially defiant individual by the time the story ends from just another ‘mother.’ Initially, ‘Mother of corpse 1084’ Sujata Chatterjee, is a traditional apolitical upper middle class lady, an employee who awakens one early morning to the shattering news that her youngest and favourite son, Brati, is lying dead in the police morgue bearing the corpse no.1084, killed in an ‘encounter.’ Her efforts to understand her son’s revolutionary activism lead her to reflect on her own alienation from the complacent, hypocritical, bourgeois society against which he had rebelled.

Significantly, Sujata makes several discoveries through her son’s death. For instance, she discovers that all her thirty-four years of her married life, she has been living a lie, as her husband, being an incorrigible philanderer, always cheated her with his mother’s and children’s tacit approval. He fixed up a petty bank job for her, when Brati was barely three years old, not out of any consideration for her economic independence, but essentially to help the family tide over a temporary financial crisis. And, as soon as the tide is over, he wants her to give up the job, which Sujata simply refuses. Later, she also discovers that her children, too, are leading lives very similar to her own. If there is someone who has dared to be different, it was her favourite son Brati. Rebellious since childhood, Brati has made no secret of his disregard, even contempt, for his familial code and value-system. Turning his back upon this decadent and defunct code, Brati decides to join the Naxalite movement of late 1960’s and early 1970’s.

Only a powerful protest writer like Mahasweta Devi could bring in the pathos of giving a ‘dehumanized identity’ to a promising young man who now turns into corpse number 1084 for the family and society. Only the mother gives him his due recognition.