Abol Tabol decoded: ‘Probasi’ translator reveals unknown facets of Sukumar Ray

সিংহাসনে বসল রাজা বাজল কাঁসর ঘন্টা,

ছট্ফটিয়ে উঠল কেঁপে মন্ত্রীবুড়োর মনটা৷

বললে রাজা, মন্ত্রী তোমার জামায় কেন গন্ধ?

মন্ত্রী বলে, এসেন্স দিছি - গন্ধ তো নয় মন্দ!

(Rough translation: The king takes his throne, the fanfare we hear/ The old minister’s mind fidgets and quakes in fear/ Says the king, what’s that smell on your clothes minister?/ Only essence, your majesty, smells good - nothing sinister!)

Thus begins Gandha Bichar, one of the gems adorning the peerless collection of nonsense poems that make up ‘Abol Tabol’, the milestone of Bengali poetry published in 1923 by a man whose 135th birthday falls tomorrow. A man who Bengalis ought to celebrate every day. For Sukumar Ray was not merely a poet. Like his father Upendrakishore and son Satyajit, he was a true polymath, always a rarity. However, since Abol Tabol is the focus today, we will regretfully leave the other aspects of his personality out of this piece.

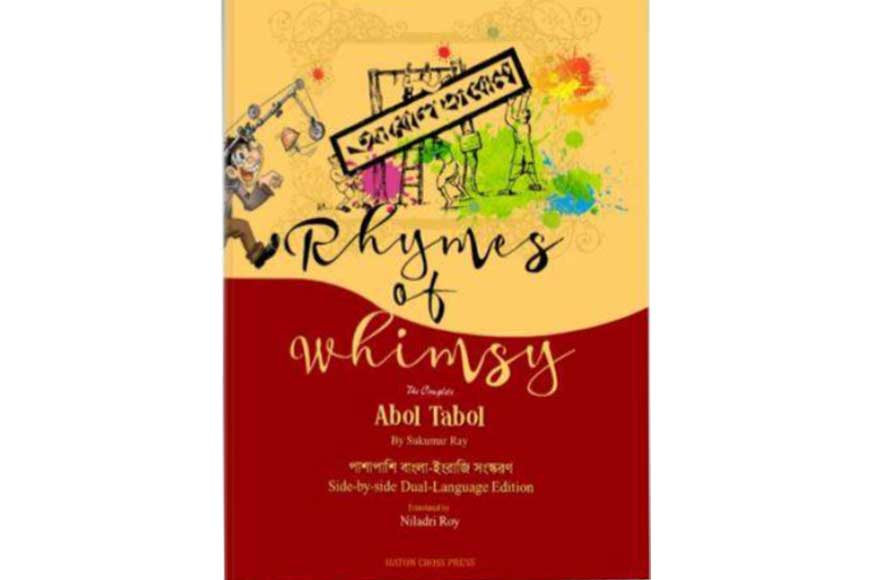

More specifically, we are focusing on the story behind Abol Tabol, as told by Niladri Roy, a San Francisco-based electronics and telecom engineer by training, and a Sukumar Ray devotee by choice. Just as an aside, the man also likes “climbing up hills” and scaled Mt Kilimanjaro in 2019, but that is a story for another day. In 2017, the former BE College Shibpur alumnus, currently an employee of Intel, published ‘Rhymes of Whimsy - The Complete Abol Tabol’, the first English translation to cover all 53 poems of the poet’s most popular work. The second part of Roy’s book (which he has now translated into Bengali and hopes to publish soon) discusses the context behind each poem. And thereby hangs a tale, as well as the reason why we chose to begin this piece with Gandha Bichar.

More specifically, we are focusing on the story behind Abol Tabol, as told by Niladri Roy, a San Francisco-based electronics and telecom engineer by training, and a Sukumar Ray devotee by choice. Just as an aside, the man also likes “climbing up hills” and scaled Mt Kilimanjaro in 2019, but that is a story for another day. In 2017, the former BE College Shibpur alumnus, currently an employee of Intel, published ‘Rhymes of Whimsy - The Complete Abol Tabol’, the first English translation to cover all 53 poems of the poet’s most popular work. The second part of Roy’s book (which he has now translated into Bengali and hopes to publish soon) discusses the context behind each poem. And thereby hangs a tale, as well as the reason why we chose to begin this piece with Gandha Bichar.

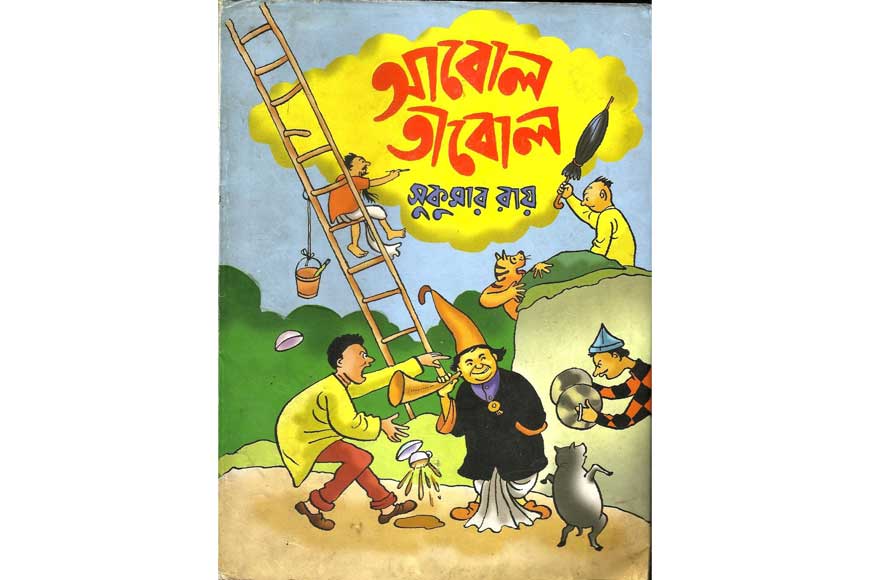

Abol Tabol

Abol Tabol

In 1922, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s Liberal Party government was shaken to its foundations by the honours, or cash-for-honours scandal. In a severely embarrassing revelation, it was found that the government was selling royal honours to raise party funds. The practice of selling honours itself was legal and dated back several centuries, primarily to enable the nouveau riche to acquire aristocratic titles. However, Lloyd George made it more systematic and brazen, charging £10,000 for a knighthood, £30,000 for a baronetcy, and over £50,000 for a peerage. The result was the awarding of honours to several criminal personalities and a meeting between a furious King George V and his Prime Minister, which eventually led to the downfall of Britain’s last Liberal government.

Gondho Bichar

Gondho Bichar

It is this scandal that Sukumar had in mind when he wrote Gandha Bichar, says Roy. “It was even found that Order of the British Empire was a title created specifically to raise funds, and nearly 25,000 people had been rewarded with it in just four years!” he laughs during a telephonic interview from San Francisco. “When the stink from the scandal spread, none of the ministers were ready with an explanation for the king, exactly as it happens in Gandha Bichar. Following the outrage, Chancellor of the Exchequer Andrew Bonar-Law took over as Prime Minister, and he is the ‘briddho nazir’ (old treasurer) mentioned in the poem.”

Roy then proceeds to reel off several more examples of such hidden messaging, which we will come to in a minute. “As I began my translations, I gradually realised two things - one, the poems weren’t merely for children. Two, each poem and even the quatrains had a message and clues embedded in it,” he explains. “Since I had definite dates for 39 of the 53 poems, I began searching around for contemporary events that would fit. I also began attempts to infer the dates of the remaining poems from what I could read of the messages hidden in them.”

Also read : Sukumar Ray and the magical world of Pagla Dashu

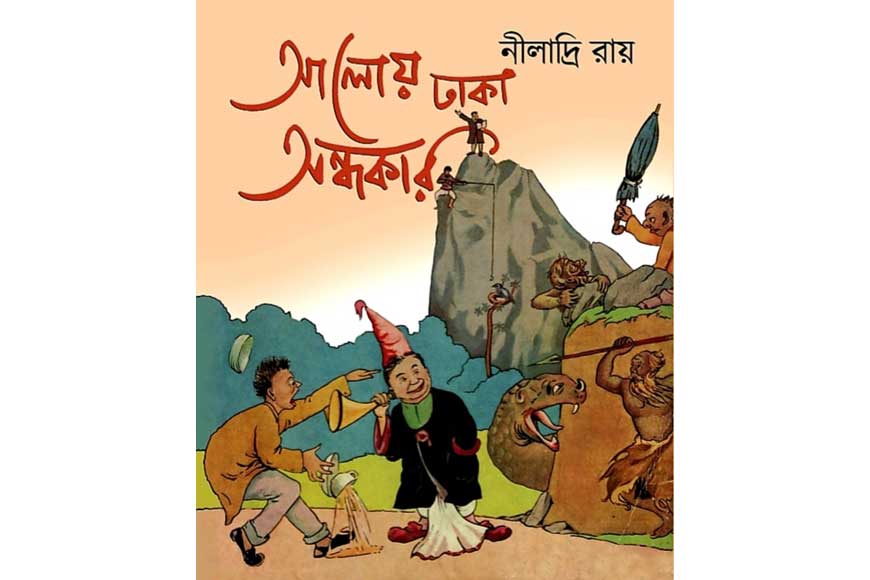

The idea that many poems in Abol Tabol contain cleverly concealed satire on the state of society and administration of colonial India has been around for some time. But it is the detective work of ‘Rhymes of Whimsy - The Complete Abol Tabol’, which has helped actually establish this theory, with plausible examples and inferences. For instance, the title of Roy’s Bengali translation, ‘Aloy Dhaka Andhakar’, is borrowed from the eponymously titled last poem in Abol Tabol, where the covert and overt messages are accompanied by a third message - that the ‘alo’ (light) of comedy hides the ‘andhakar’ (darkness) of satire, Roy says.

Rhymes of Whimsy

Rhymes of Whimsy

Why was Sukumar embedding secret messages in his poems? The simplest answer is that nonsense rhymes seemingly written for children were the best possible disguise for messages of an anti-colonial and subversive nature, and the author’s masterful way of avoiding censorship by the British administration, which was paranoid about “seditious and subversive literature”. And as Roy points out, Sukumar left clues in the poems to indicate if his readers had correctly interpreted his messages.

To offer a couple of other important examples without giving away too much for those who wish to read the book, Roy posits that the poem ‘Danpite’ is all about the Treaty of Versailles (1919), and the conflict that ensued between the three principal signatories - French Premier Georges Clemenceau, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and US President Woodraw Wilson (the ‘Tom chacha’ in the poem). For those not in the know, the treaty held special significance for Bengalis because the British nominated Bengal’s first baronet Lord Satyendra Prasanna Sinha as the Indian signatory, though he politely turned down the offer.

Aloy Dhaka Andhakar

Aloy Dhaka Andhakar

Again, ‘Ekushe Ain’ is a clear reference to the notorious Rowlatt Act of 1919, while in ‘Paloan’, the poet paid homage to Bhim Bhabani aka Bhabendra Mohan Saha, the celebrated wrestler who died of pneumonia in 1922, when he was just 33. Sukumar himself was to follow in 1923, dying at 35 of a severely infectious fever known as leishmaniasis, for which there was no cure at the time, leaving behind the two-year-old Satyajit and his young mother Suprabha.

Nearly a century later, we finally have a complete translation of Abol Tabol. Most of the poems had appeared in the children’s magazine Sandesh (founded by Upendrakishore in 1913) between 1915 and 1923. “Sukumar curated only those poems which contained a double meaning,” says Roy. “Three poems - the first and last, both titled Abol Tabol, and Gandha Bichar - appear to have been written specifically for the collection.”

Thanks to the ‘probasi’ engineer, the world now has a chance to experience the outstanding brilliance of one of Bengal’s literary giants. Does Roy plan more Sukumar Ray translations? The Pagla Dashu stories, for example? He thinks not, but never say never, is our motto.