A life dedicated to Lata Mangeshkar

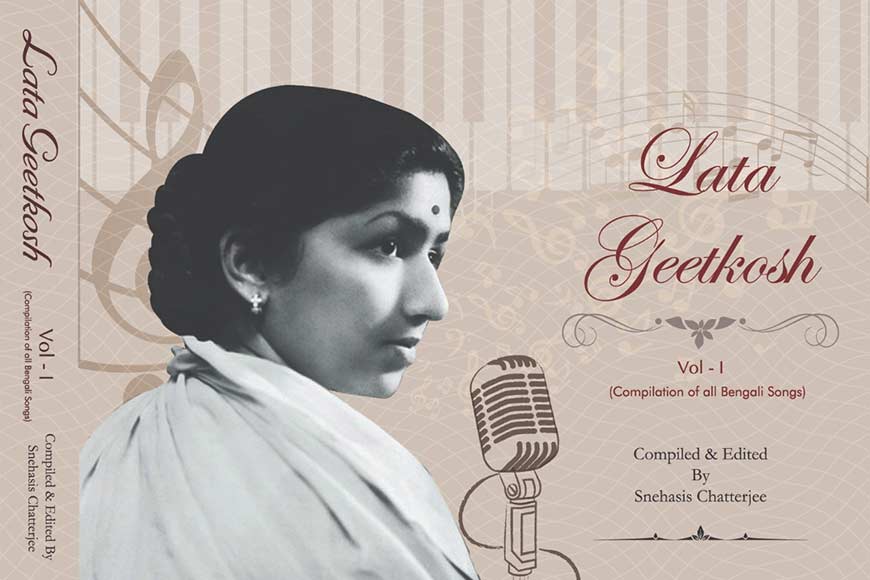

Snehashish Chatterjee is a strange man. A man who has dedicated most of his life to creating a wonderful musical archive comprised entirely of the music of Lata Mangeshkar. A career government servant, he has not allowed his job to interfere with his passion, and even doubled as a music teacher, running classes at home. Understandable, as music runs in his blood, and a young Snehashish began his training under the direct guidance of his mother. But his lifelong obsession has been the encyclopaedic archive he is building, featuring every single song that Lata has sung over the years, contained in a series of books titled ‘Lata Geetkosh.’

Till date, he has published 12 volumes of Lata Geetkosh, having begun the journey way back in 1990. Currently, he is working simultaneously on the targeted 15 volumes of Lata Geetkosh, the first volume of which contains every small detail of Lata’s Bengali songs.

“As a student at Rampurhat College in Naihati, I had a dream. To compile a database that would contain every single song Lataji had sung, to be available to music lovers and practitioners across the world, keeping her work alive for future generations. So I began the work in-between college lectures. But at that time, I wasn’t very serious and didn’t imagine that it would lead to something as big as this.” Earlier, Snehashish had studied music under Dhrubatara Joshi, and Rabindra Sangeet in Santiniketan under such legendary tutors as Neelima Sen, Kanika Bandopadhyay and Santideb Ghosh. “When I was in Class V in 1971, I happened to watch Johnny Mera Naam, and I almost went into a trance when I heard the number Babul Pyare…The song exerted some mysterious power on me, and I fell in love with the voice that sang it. As I soon learnt, it was the voice of Lata Mangeshkar,” he says.

“Studying in Rampurhat College between 1981 and 1983, I discovered a shop that sold gramophone records. I began noting down every detail from the records, mainly of Lata Mangeshkar,” says Snehashish. What kickstarted the documentation is what he read in the papers about Mohammad Rafi’s body of songs, which began to emerge after the singer’s death in 1980. He found that there was no consistency in the number of songs Rafi had recorded during his lifetime. “This made me realise that there was an urgent need to document the songs sung by different singers to arrive at the right number. And I decided to begin with my favourite singer,” says Snehashish.

His encyclopaedic record of Lata’s songs includes songs in different languages, private recordings, and film songs, over an extraordinarily long career. “She was our national pride and many of us worship her as Goddess Saraswati in human form. Instead of complaining about what has not happened, I decided to do something about it myself,” he says.

“In 1990, I met Haru Babu (Sundarlal Mukhopadhyay), who was an avid collector of records. He guided me painstakingly on how to catalogue my collection properly and scientifically. Without his help, I would never have learnt how to create this archive. The first volume comprised Lataji’s Bengali songs and came out in 1997, and it was possible only because of Haru Babu’s guidance,” says Snehashish.

In the days before Internet and social network platforms, collecting source material such as souvenirs and testimonials was a daunting task. In the early 1990s, India did not even have courier services. Snehashish would assemble a lot of the material from Kolkata’s Wellington Square and Sealdah markets, and from cities like Mumbai, Hyderabad, and even some shops in Puri. “Two songs from the Odia films Arundhati and Surjamukhi were accessed from Bhubaneswar. I even collected material from overseas like California and Sharjah. Slowly, friends and well-wishers began to pitch in with pictorial and textual data, through letters and parcels and so on,” he explains.

As of now, Snehashish says that from the 11 published volumes, one can obtain details of 5,158 songs, including song title, the music director, the film (if applicable), the lyricist, the year in which it was recorded, and the complete lyrics, so that a music researcher can use this as a single source. The remaining four volumes will contain roughly another 1,500 songs. As of now, Snehashish has nine volumes of Hindi songs, one volume of Bengali songs, one of Marathi and one volume of Konkani songs. According to Snehashish, Lata sang around 7,000 songs in 38 languages, including Malaysian, Swahili, Russian, English and others.

“I still don’t know how many songs she sang throughout her life, but media reports say that she has lent her voice to around 7,000 songs. I am now looking for the songs she sang in Russian and Latin. Most of us are not aware that Lataji also sang in languages like Malaysian, Swahili, Russian, English and other foerign languages,” he says.

For such a dedicated devotee, when did he personally meet his icon? Well, it was a long, long struggle. “I used to write letters to her informing her of my work. But she never wrote back so I had no idea if she even knew about me. Then in 1993, she came to Kolkata to sing at a musical conference at the Salt Lake Stadium where Harish Bhimani was the anchor. I knew Bhimani ji quite well, so I sought his help to approach Lataji. I met her in the green room during a break and to my pleasant surprise, Adinath Mangeshkar, her nephew, introduced me as the ‘Bangali Babu’ who was working on her music. I was thrilled to know that he knew about my work and so did she. She patted my back and gave me her personal number, telling me to call her directly whenever I got stuck somewhere.”

He met her again in 2006 at Prabhu Kunj, her home in Mumbai. “That was one of the best days of my life. After a little talk about music, I requested to see her room. She was surprised. ‘There is nothing in my room,’ she said. She was right. It was a simple room, a single bed with drawers, a dressing table, and a small wardrobe. What was interesting was a big poster of a little child with fingers on its lips and the word “silence” in bold letters written across the face. Beneath this was written, ‘Genius Inside’.”

The relationship was close enough for Lata to christen Snehashish’s music school, which he set up in 2007. “It is called Swarganga because ‘swar’ means voice while Ganga is the river flowing along the place where the school is located in Serampore,” says Snehashish, who teaches all the common genres of music, from Hindustani classical to Rabindra Sangeet, and including Atul Prosadi, Nazrul Geeti, Rajanikanta’s compositions, Dwijendrageeti, folk, adhunik and Shyama Sangeet.

Today, Snehashish is struggling to gather funds to keep building his archive and publish the remaining volumes of Lata Geetkosh. But he is determined to keep it alive for posterity. One hopes he can keep his archive alive and growing, if only as a tribute to the musical genius who gave 80 years of her life to music.