A century-old library struggles to stay alive - GetBengal story

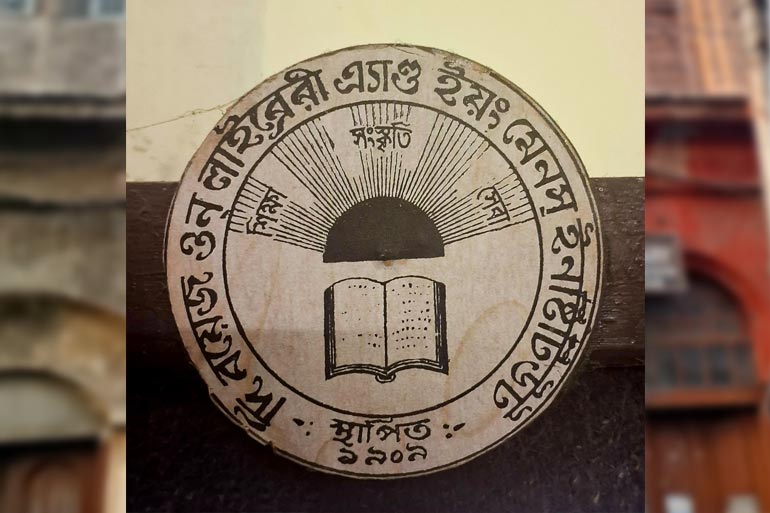

The Boys’ Own Library and Young Men’s Institute — a library over a century old, is now on the verge of shutting down. Once founded by three young men with a vision to create a dedicated reading space in the heart of Kolkata, this iconic institution has been a haven for countless readers for more than a hundred years. Today, however, it is crumbling— physically and in spirit, due to a lack of readers and proper infrastructure.

In any discussion about libraries, the term ‘reader’ becomes crucial — especially the general reader. To understand how the concept of a public library came, we need to turn back the pages of history to the time of Macaulay’s Minutes in 1835. It was in this period, on August 20, that a meeting held at Kolkata’s Town Hall passed a resolution to establish a public library. This led to the founding of the Calcutta Public Library on March 9, 1836, on Esplanade Row. Over time, the library underwent several transformations — first becoming the Imperial Library, and after independence, reopening as the National Library in 1948.

The reason for diving into this history is simple — what we now understand as a public library didn’t really exist before. Back then, libraries were mostly personal collections housed in private homes. While some consider the Asiatic Society to be the first library, it was never truly a public one, in fact, until 1828, Indians weren’t even allowed entry.

If we shift the focus to libraries started by the common people, the United Reading Room, established in 1872 at 67/1/2 Nimtala Ghat Street, stands out. It could very well be regarded as one of the earliest public libraries created by and for the people.

It’s interesting to note that soon after Macaulay’s Minutes in 1835, efforts to create public libraries started to take shape. As we all know, Macaulay’s education policy was largely aimed at producing clerks loyal to the British administration. Yet, around the same time, the rise of public libraries reflects something far more significant, a shift in the socio-economic fabric. The spread of Western education went hand in hand with the rise of public libraries.

Whether these libraries were meant to quench the thirst for knowledge or simply serve as tools of a larger educational machine, that question still lingers.

Let’s return to the story of The Boys’ Own Library. It all began on May 1st, 1909 when three students of The Boys’ Own School and Kindergarten — Jibankrishna Dey, Pradyutkumar Rudra, and Krishnaprasanna Ghosh, started the library with just twenty textbooks and an old cupboard. Naturally, the library took its name from their school.

The library’s first address was at 12 Ram Narayan Bhattacharya Lane, in the home of Dr. Girish Chandra Dutta. And if you look closely at the initial booklist, it only featured school textbooks. Membership cost just two annas a month, and there was no separate entry fee.

From its early days, the library saw many changes. It took almost fifty years to find a permanent home. Over time, the address kept shifting — from 7/3 Beadon Street to 71 Masjid Bari Street, and later 76/2 Bidhan Sarani. Of all these, only the house on Bidhan Sarani had a sense of stability before they moved into the current building.

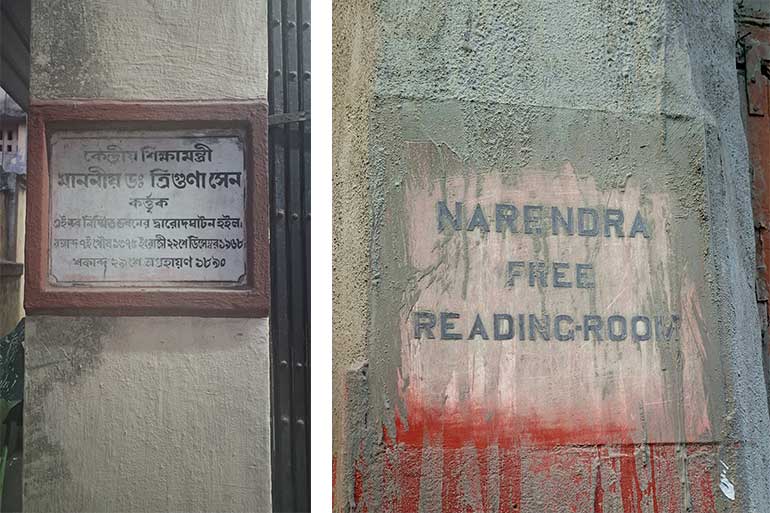

In 1936, thanks to the generosity of Kalishankar Mitra, the library was able to rent its current space, free of cost. The reading room in this building was named after his father, with a plaque that still stands proudly today: "Narendra Free Reading Room". Until just a few years ago, this space was open regularly. People would drop in to read newspapers and important books, completely free of charge. It was a valuable resource, especially for students from less-privileged backgrounds.

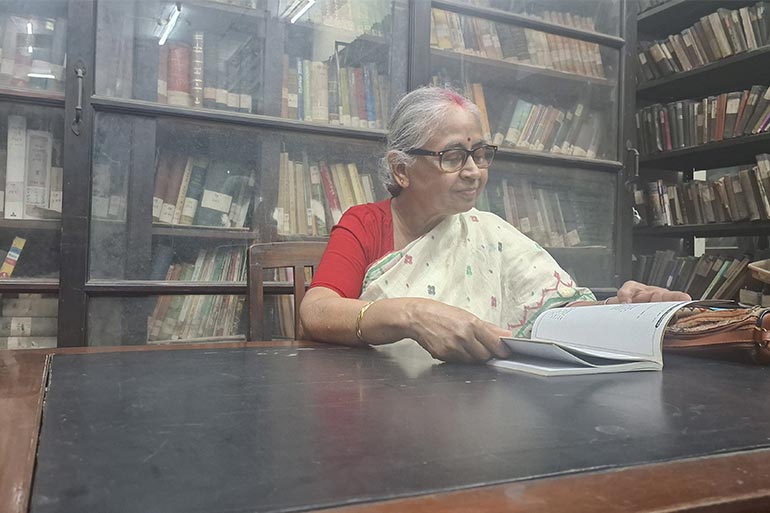

But times have changed. Mita Gupta, the assistant librarian, told Bangadarshan.com (another portal of GetBengal), “Most of us who manage this library do it voluntarily, without pay. A few months ago, we noticed newspapers, books, and important documents going missing from the reading room. We had no choice but to shut it down. We simply couldn’t manage everything on our own — we don’t have the infrastructure for something like CCTV. And when people themselves show such little ethics, what can we do but close the doors?”

Despite being lovingly referred to as the “small library”, this space was once a lifeline for many. Now, it’s struggling to survive.

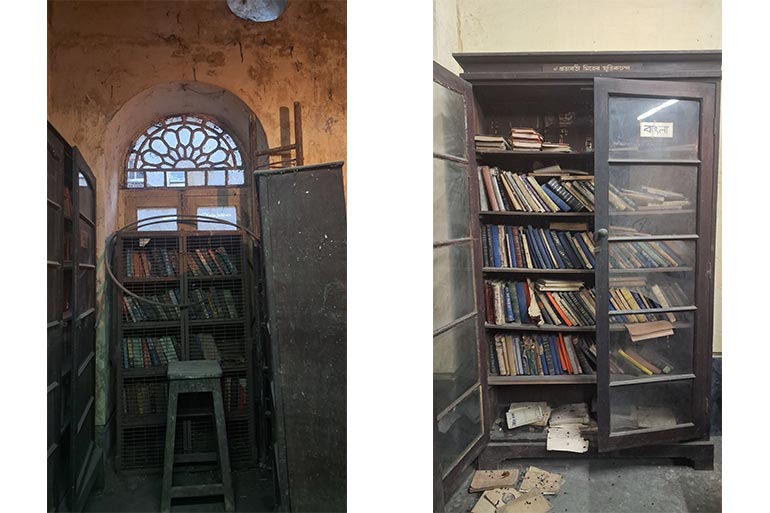

When the assistant librarian Sanjay Babu was requested to unlock the building that day, a heartbreaking scene unfolded — the once-vibrant library had become a shelter for rats and pests. Dust-covered shelves, decaying books, and crumbling cupboards told a story of neglect. Hidden behind the city’s glitzy high-rises, another piece of Kolkata’s living history was fading into silence.

Given the word “boys” in its name, the library's early collection and activities were understandably limited in scope. For a long time, Bengali novels and plays had no place in its catalogue — while English books, unsurprisingly, were always welcome. (It’s hard not to be reminded of Macaulay’s infamous Minutes here.) That began to change when the renowned playwright Dwijendralal Roy donated a signed copy of his play “Mewar Patan” to the library. This marked the beginning of the inclusion of Bengali drama. Soon after, Bengali novels also found their place — but with restrictions. Readers under 16 were not allowed to borrow them. Even Bankimchandra’s novels were initially excluded.

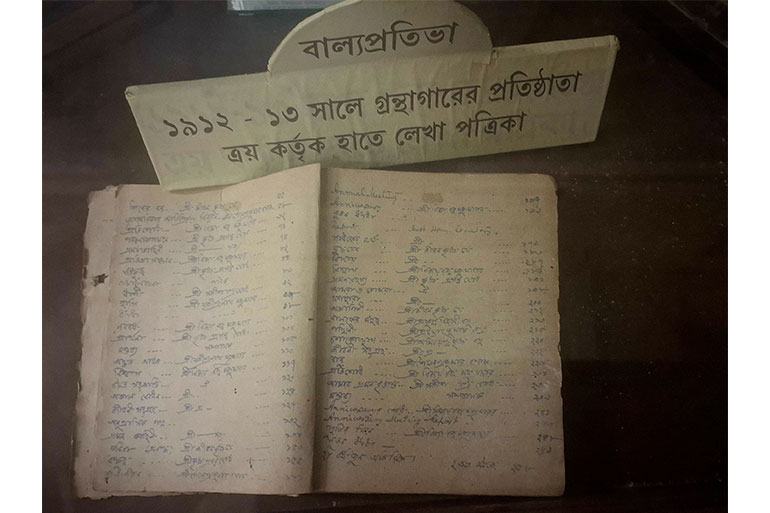

Over time, however, the library’s conservative mindset began to evolve. Annual events became a regular feature. In 1915, during the library’s sixth annual celebration, a play titled “Sanshodhan” by writer Bijoykrishna Majumdar was staged. Interestingly, since 1912, the library had been publishing a handwritten magazine called “Balyapratibha”, which Bijoykrishna would later go on to edit.

However, the staging of “Sanshodhan” became controversial due to the idea of young male members dressing as women for female roles. "How shameful!" some declared. Yet despite the backlash, the show went on, with the founding trio themselves performing in it. This play became the library’s first-ever theatrical production.

Since then, the tradition of theatre continued year after year — and so did the debates. During the library’s silver jubilee, the play “Zohra”, featuring a courtesan character, triggered moral criticism. Later, in 1957, “Keranir Jibon” was staged at Rangmahal for the annual celebration — this time, the female roles were played by the library’s women members themselves. In many ways, these performances were milestones in the history of amateur theatre in Bengal, bold, significant, and ahead of their time.

In the rich tapestry of Bengali literature and culture, The Boys’ Own Library has been much more than just a library, it has been a vibrant cultural hub, engaging deeply with the arts in many forms. One remarkable example is its contribution to amateur theatre. It’s rare to find a library that has staged over 100 plays and earned consistent praise from critics and connoisseurs alike.

The library’s first literary venture began in 1912 with a handwritten magazine. Although it ran for a few years, it eventually ceased. Decades later, in the 1970s, a wall magazine called “Pakshiraj” was launched under the editorship of Soumitra Mitra. However, due to a lack of support and manpower, that too became irregular over time.

As the library’s activities outgrew its original boyhood image, a transformation was inevitable. In 1917, the name was officially changed to The Boys’ Own Library and Young Men’s Institute. The institution evolved quickly. In the 1930s, it opened a dedicated children’s section. By the 1940s, a fund was created for building a permanent space. In 1960, the library bought land on Dalimtala Lane for Rs. 36,500. The foundation stone of the present building was laid in 1962 by the eminent physicist Satyendra Nath Bose. Construction was completed in 1968, and the new building was inaugurated by Dr. Triguna Sen, then Union Minister of Education and founding Vice-Chancellor of Jadavpur University. The event was chaired by the legendary writer Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay.

Over the years, many luminaries have served as presidents of the library, including noted author Khagendranath Mitra and the first Bengali Accountant General, Jyotishchandra Mitra. The library has also hosted lectures by literary stalwarts such as Premendra Mitra and Narayan Sanyal.

In his History of Calcutta Streets, renowned Kolkata historian P.T. Nair points out a unique moment in 1981. On the occasion of the library’s 37th Foundation Day, the Kolkata Municipal Corporation renamed Dalimtala Lane as Boys’ Own Library Row in honour of the institution. A street being renamed after a library, that too in Kolkata, is a testament to the institution’s enduring legacy in the cultural history of the city.

Despite bearing witness to over a century of history, the future of The Boys’ Own Library and Young Men’s Institute now hangs in the balance. Samir Dey, son of founder Jibankrishna Dey, still visits the library, undeterred by the challenges of age at 83— driven by nothing but love for books. Others too, from different corners of the city, come voluntarily to keep the library alive, offering their time and effort without expecting anything in return.

Government grants have stopped coming for years. Today, the library survives on dwindling savings. To generate some revenue, a small theatre hall has been built within the premises, where performance groups can rent the space at affordable rates. A rehearsal room is also rented out to theatre troupes. That’s the only steady source of income left.

As per Mita Gupta, “With no funding, we can’t maintain the place properly, and we’ve stopped buying new books altogether.”

A shared concern echoed among the caretakers, children no longer come like they used to. And those who do, rarely show interest in Bengali books. Some teenagers in classes nine and ten have never even heard that “Feluda Samagra” exists as a single book. They only recognize English paperbacks and comics. Whose fault is this? Is it the fault of time, or of society?

Standing quietly in the face of this uncertain future is a library that once echoed with readers and performers, a library whose fading shelves still hold over 40,000 books and magazines, their pages yellowed with age. The Boys’ Own Library now waits, not just for readers, but for a revival, or at the very least, remembrance.