Poetry for Sukanta Bhattacharya was born from the trauma of war and famine - GetBengal story

The city was a site of continual trauma and degradation of the human subject during the Bengal Famine that demanded a kind of poetry where ‘Our history will be shaped by/ Hungry stomachs.’

As the young and rebellious poet, Sukanta Bhattacharya asserts in uncompromising tones:

My Spring goes by/ Waiting in queues/ For food/ My sleepless nights

Are torn by/ Vigilant sirens (“To Rabindranath”)

The famine of 1943 was a direct result of British policies of food control and hoarding. At a conservative estimate, around 3 million people died of hunger or starvation-related deaths in 1943 and 1944 as the famine waged on. It left a deep scar on Bengal’s psyche because the long irrevocable trauma of war, famine and communal conflagrations made the 1940s one of the most memorable decades in Bengal’s history.

Responses to the famine resulted in the rise of a group of poets who came to dominate Bengal’s literary scene after Rabindranath Tagore’s demise in 1941. Poets like Sukanta Bhattacharya, Premendra Mitra, Buddhadev Bose, Arun Mitra, Samar Sen, Biren Chattopadhyay, Subhash Mukhopadhyay, Golam Kuddus, Fahrrukh Ahmed and Dinesh Das tried to dislodge Bengali poetry from the romantic philosophical Tagorean verses and replace them with a new incisive imagery of the urban landscape and its destitutions.

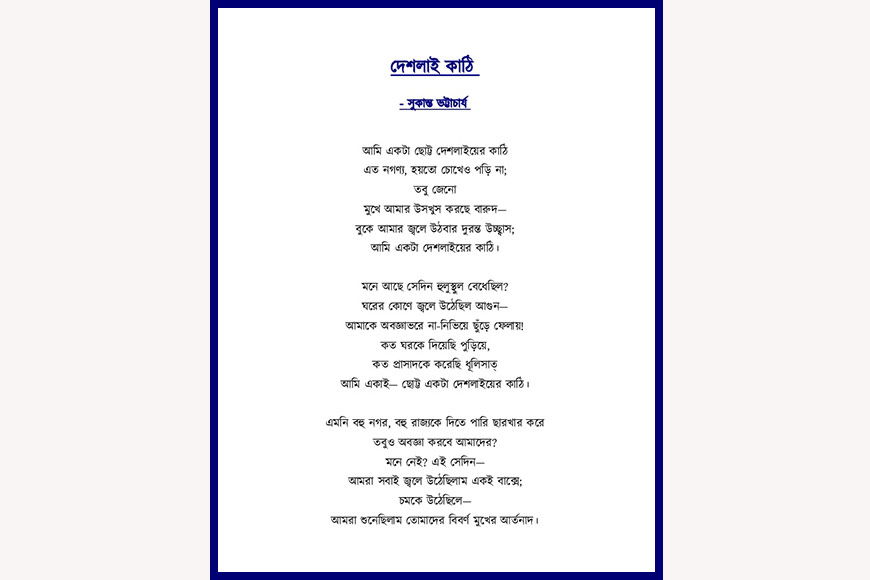

The poem, Deshlaier Kathi by Sukanta

The poem, Deshlaier Kathi by Sukanta

Their poetry was written in response to the suffering they witnessed on the city streets, the cries of the multitude as they begged for phyan or lay dead on streets, while scavenger birds pecked their hunger-ravaged corpses. The city, besieged by poverty and torn apart by war, had become a center of depravity, sickness and moral vacuum. These young poets felt the need to express themselves in a new, raw and more intense realistic language, encapsulating the astounding violence that the city and the province were reeling under.

Sukanta Bhattacharya (1926-1947) was a prodigy whose untimely death at the age of 21 perhaps deprived our literature of many significant works. Yet, the few pieces he wrote during his short life were adequate to carve a permanent place for him in the Bangla literary pantheon. A youth inspired by communist ideas, Sukanta depicted the grim life of the poor in his poems. ‘Hay Mahajiban’ (O Great Life) is perhaps the most famous of those – one that ties poverty and poetry with a harshness that betrays his own perceived nature of the genre:

O Great Life

of Hunger, the world is prosaic:/ The Full Moon appears to be a scorched bread O Great Life! No more of this Poetry,/ Now bring the hard, harsh Prose,/Let the poetic-tender-chime dissolve,/ Strike the tough hammer of Prose today!/ (We) need not of the softness of Poetry–/ Poetry, today I give you a break, / For in the realm – (Chharpatra, 1947; Translation by Osman Gani)

Also read : Why Jibanananda’s Banalata Sen is a cult poem?

Sukanta, the teenage rebel poet was born to Nibaran Chandra Bhattacharya and Suniti Devi in Kolkata. His father was the owner of the Saraswat Library. Sukanta lost his mother Suniti Devi, to cancer, at a young age. His family hailed from Faridpur district in erstwhile East Bengal but he was born in Calcutta at his maternal grandfather’s place, where his father later moved in with his family. Sukanta was a quiet and introvert child who started writing from a very early age. He expressed his myriad emotions with honesty in his works that reflect the inner child in him, giving us a glimpse of his deep-rooted fears, insecurities, a despondency and over-powering gloom that enveloped him.

Sukanta’s poems take the reader on a roller-coaster ride of emotions. If in one open he sounds depressed, in the very next one may be, his tone is upbeat and buoyant. Again, if one poem expresses his hurt, in the very next, he speaks of resilience. In ‘Runner’, he portrayed the pain of the men who walked miles to deliver letters to faraway places, while ‘Priyatamasu’ described a mercenary’s homeward journey after fighting many a war for others.

Sukanta would surprise all with his metaphors and similes, even at the cost of aesthetics at times. His heart bled for the poor and downtrodden. In a matter-of-fact pointer to hunger, Sukanta compared the full moon to a burnt chapatti. Again, in a short poem, he traced the life-cycle of a chicken -- from its desire to eat good food to landing on the dining table as food! He wrote about the “exploited” Cigarette, and the “small and insignificant” but “explosive” Matchstick. The symbolism in ‘Deshlaier Kathi’ (The Matchstick) is hard to miss. In the poem, the poet speaks to the bourgeoisie and the elite of our society through a metaphor that is seemingly insignificant and a mere convenience to most of us, but also one that holds the potential to burn the loftiest of palaces down to rubble. To some, it is literally a matchstick, but to others, it is the proletariat who rear a flame that can burn down the hierarchies of this world.

Works of Sukanta Bhattacharya

Works of Sukanta Bhattacharya

He wrote about the middle class, the labourers, the soldiers, the enemy, the farmer. He wrote of Kashmir, Manipur and Rome –encompassing all he could in his short life. Most of his poems were scribbled in bits of paper that lay scattered around. ‘Chhinnapatra’, is a compilation of Sukanta’s poems he wrote between 1943 and 1947 and it was published book of poems a few days before his death.

Had he lived three more months, Sukanta would have got the best birthday gift of his life. Three months and two days after the revolutionary poet breathed his last, his beloved country achieved its hard-earned Independence – on 15th August, 1947. Kavi Sukanta, as he was popularly known, would have turned 21 that very day. But that was not to be. Tuberculosis snuffed life out of the young and promising poet.